Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

The Freeman Girls

Mary Jane Conner

Sylvia Conner

Captured Faces

Henry Bibb

The Inalienable Right to be Free

Jim Hercules

Freedom with the Joneses

Sara Baro Colcher

George O. Brown

John Dabney

Letter from a Freed Man: Jourdan Anderson

Siah Hulett Carter: Escape on the Monitor

Ruth Cox Adams

Ellen Craft

No Longer Hidden

The Woman Who Escaped Enslavement by President Geo…

George W Lowther

Edmondson Sisters

The Truth's Daughter

Please Hear Our Prayers

Caldonia Fackler 'Cal' Johnson

Hugh M Burkett

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

William Still

G. Grant Williams

Robert J Wilkinson

Michael Francis Blake

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

Mr. Hendricks

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Robert H McNeill

Wendell Phillips Dabney

Orrin C Evans

Dr. William A 'Bud' Burns

Matthew Anderson

William Monroe Trotter

James E Reed

Henry Lee Price

Frederick Douglass

Samuel R. Lowery: First Black Lawyer to Argue a C…

Edward Elder Cooper

Columbus Ohio's First African American Aviator

James Forten

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

79 visits

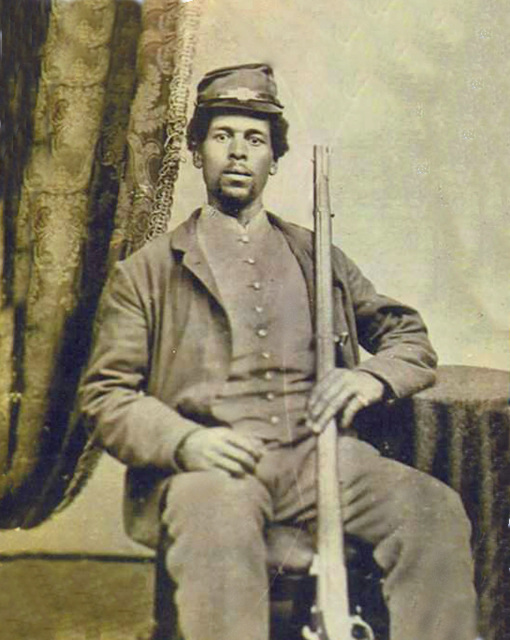

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazard

His fate and freedom were nearly stolen from him in September 1839, when he was just 8 years old. On a late summer day two kidnappers appeared in Worcester. They got to work just after dawn prospecting for potential victims among the town's people of color. The two men, posing as merchants in need of a boy to work at a shop in Palmer, stopped John Metcalf at the corner of Main and Front streets. Mr. Metcalf recognized the younger of the two as Elias Turner of Palmer. He had never seen the other man.

Mr. Turner asked where they might find a "colored boy." "What do you want of a colored boy?" Mr. Metcalf wondered. "For the old man," Mr. Turner replied, perhaps meaning his father in Palmer. Mr. Metcalf said he couldn't help them. Then he watched as they ambled off down Front Street, headed toward Pine Meadow. It was Thursday, Sept. 12, 1839. Worcester was a town surrounded by farms, and its small community of free people of color mostly lived in Pine Meadow. In Pine Meadow, the two men posing as Palmer merchants knocked on Fanny Proctor's door and asked for one of her boys. Samuel Johnson later recalled the unfamiliar white men asking him the same question.

One of the men, Elias Turner, had been spotted a few days before in Shirley asking local officials there if he might employ a black boy from the town's poor house. The overseer of the poor sent Mr. Turner away empty handed. But in Lunenburg, Caira Hazard had been swayed by a similar offer of employment for her son, Nahum. Two unfamiliar white men had come to her house on Monday, Sept. 2. The strangers said they operated a tavern in Western Massachusetts, about 60 miles away over the mountains. If young Nahum would come work in the tavern, they promised to see to his upkeep and education.

The solicitation wasn't unusual for the times. The men offered a kind of apprenticeship that then was common for poor boys of any race. A local man had vouched, falsely as it turned out, for the two strangers.

As a widow with several children to care for, Mrs. Hazard accepted the offer and allowed Nahum to go with the men. But there was no tavern. The men, in fact, planned to enrich themselves by selling her free born son into bondage in the slave markets of Virginia, and they hoped to get another boy or two before heading south. One of the men who called on Mrs. Hazard was Dickinson Shearer, a former resident of Palmer who had moved away years ago, eventually ending up in Cartersville, Virginia, on the outskirts of Richmond. The other man was likely Francis Wilkinson, a Virginia slave trader.

Ten days later, Mr. Shearer and his nephew, Mr. Turner, appeared in Worcester's Pine Meadow posing as shopkeepers. They didn't have Nahum Hazard with them at the time. It's not clear where they had stashed the boy. The kidnappers eventually found their way to the home of John and Diana Francis, members of Worcester's small black community. Mrs. Francis heard men outside speaking to her 8 year old son, Sidney, and went out to see what they wanted. Mr. Shearer launched into his pitch, claiming he had a store in Palmer selling goods from England and the West Indies. He said young Sidney looked to be a smart lad and offered to take him on in the shop. He promised to send the boy to school in the summer when there was less work to do.

"He said he wanted him to do chores and light work about the house and store, and take care of a horse," Mrs. Francis later recalled in court. Mr. Turner said he'd write with news of Sidney and that, at any rate, the railroad would soon reach Palmer, so Mr. and Mrs. Francis could visit easily. Mrs. Francis sent the men to where her husband was working nearby at a railroad depot. After conversing with the men a while, John Francis gave his consent. He took down the men's names in his account book, but he'd later learn both gave false identities. An hour and a half after they had arrived at the Francis home, Shearer and Turner departed with Sidney in tow.

Something in the arrangement or the demeanor of the men apparently left Mr. Francis feeling unsettled. After asking around for a few days, he set off for Palmer on foot on Sunday, Sept. 15, with $3 in his pocket. He would end up being away for nearly two weeks trying to pick up the men's trail after finding no trace of them in Palmer. As Mr. Francis walked west that Sunday, his son and Nahum already had been taken more than 400 miles from Worcester. The boys had nearly reached Fredericksburg, Virginia, in a series of stagecoaches, steam boats and trains.

In Fredericksburg, one or both of the boys created a commotion by asking for a book to pass the time and reading aloud from advertisements posted in a barbershop. Word of the supposed slave boys who could read, an implausibility in the South of the day, eventually reached the ears of J.P. Lipscomb, a local man who correctly sniffed out the unfolding kidnapping. By that time, the boys had been taken to Richmond and then on to Cartersville by Francis Wilkinson. Mr. Wilkinson likely had been the man who visited the Hazard home in Lunenburg with Mr. Shearer.

Mr. Lipscomb soon showed up in Cartersville with a constable and demanded to speak to the boys. Sidney was found in Mr. Wilkinson's cellar. The boy told Mr. Lipscomb and the constable he was from Worcester and that his parents had only consented for him to go a short distance away. The constable arrested Mr. Wilkinson and Mr. Shearer and took them and Sidney back to Fredericksburg to sort the matter out. It's not clear if Nahum went with them that day or followed later.

A letter explaining the situation written by Fredericksburg Mayor Benjamin Clark arrived in Worcester on Thursday, Sept. 19, a week after Sidney had been taken. The town was in an uproar. News of the kidnappings roiled Worcester from the modest homes of Pine Meadow to the wealthy white households along Elm Street. Levi Newton, nephew of former governor Levi Lincoln, struck an indignant tone writing in his personal diary that Sunday. "Today I hear of an outrageous case of stealing a negro boy from this town," Mr. Newton wrote.

Two days later, George and Benjamin Rice of Worcester left for Fredericksburg having been assigned to fetch Sidney and one of the prisoners, Mr. Shearer. A man from Lunenburg already in Virginia on business was tasked with bringing Nahum home. Mr. Turner was arrested in Palmer.

The Massachusetts Spy newspaper printed an account of the kidnapping in which the writer noted the tumult gripping the town: "The circumstance has produced a strong sensation here, and much indignation is felt at the commission of so daring an outrage."

As Worcester fumed, Mrs. Hazard in Lunenburg still had no idea what had become of her son. She had fretted for his safety since hearing of Sidney's disappearance from Worcester.

On Thursday, Sept. 26, George Bradburn of Boston arrived in Lunenburg to investigate the circumstances of Nahum's abduction. It was the boy's 9th birthday. Mrs. Hazard recounted to the Bostonian the story she had been told about her son going to work in a tavern. "The mother had no further knowledge of him till I informed her that he was in Richmond, Va., having been rescued from the hands of kidnappers," Mr. Bradburn reported in his account.

"Joy enough, I assure you, was diffused through the bosom of this mother when I assured her that her son was safe, and would soon be restored to her arms again," he wrote.

Mr. Wilkinson, the Virginian, was charged with Nahum's kidnapping but escaped from jail in Richmond that December before he could be brought to Massachusetts to stand trial. Shearer and Turner were tried in the Worcester Court of Common Pleas in Lincoln Square on Jan. 23, 1840. Col. Pliny Merreck, the prosecutor, said it was obvious to anyone that Shearer was guilty of kidnapping and scheming to sell free people into slavery. In his closing arguments, Col. Merreck sought to convince the jury that his nephew and accomplice, Mr. Turner, was equally culpable.

"We found him going with Shearer in quest of colored boys, making that the first subject of inquiry whereever they went until they succeeded," Col. Merreck reminded the jury. The jurors deliberated less than an hour before returning guilty verdicts. They recommended Mr. Turner receive mercy. Mr. Shearer was sentenced to seven years of hard labor, and his name was lost to history after the trial.

Sidney Francis died of tuberculosis in March 1850 at age 19. Nothing is known of his life after he returned to Worcester. His father, John Francis, helped jeer and pelt fugitive slave hunter Asa Butman in 1854 as part of an angry mob that gathered in Worcester to shoo the unwanted visitor out of town. The incident came to be known as the Butman Riot.

Nahum Hazard later returned to the South as a soldier in the Union Army. He was assigned to the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, the second of the so called colored regiments mustered from black and mixed race volunteers. Pvt. Hazard was wounded in November 1864 at the Battle of Honey Hill near Grahamville, South Carolina.

After the war, he returned to northern Worcester County. One of his descendants in the area, Beverly Monroe, 86, of Leominster, recalls hearing family stories about her notable great-grandfather when she was a young woman. Mrs. Monroe said her grandmother, Catherine Thomas Hazard, was one of Nahum Hazard's daughters. Mrs. Monroe wrote a fictional account of the kidnapping of her great-grandfather told from the perspective of the boy's mother, Caira Hazard.

"I tried to picture the terrible travail of waiting all those weeks for word of him," Mrs. Monroe said. "As a mother, I'm so sympathetic to that. I can't image one of my sons being taken off." Mrs. Monroe said she has always been moved by the notion that, in a sense, her great-grandfather was saved from slavery by education. "He knew how to read, and that was unusual for the boys in the South who were slaves, the poor things," she said. "In those days, slavers were capturing people willy-nilly and most of them didn't escape."

Musician and playwright Dillon Bustin of Marshfield was inspired by the story to begin writing a series of musicals based on the extraordinary life of Mr. Hazard. "He left nothing in the way of personal expression that I'm aware of, no letters," Mr. Bustin said. "But he was a survivor. He was highly adaptable."

Seventy-four years to the day after he had been abducted, Mr. Hazard died in Leominster on Sept. 2, 1913. He was a few weeks shy of 84 years old.

Nahum Gardner Hazard is buried on a shady edge of Townsend's Hillside Cemetery, next to his wife, Harriet, and three of their children who died young. On the small tombstone commemorating an 8-month-old girl named Helen and an unnamed infant son, the grieving parents had these words chiseled: "Sleep on dear babes and take your rest."

Source: Telegram Gazette, Thomas Caywood (Feb. 10, 2014 edition)

Mr. Turner asked where they might find a "colored boy." "What do you want of a colored boy?" Mr. Metcalf wondered. "For the old man," Mr. Turner replied, perhaps meaning his father in Palmer. Mr. Metcalf said he couldn't help them. Then he watched as they ambled off down Front Street, headed toward Pine Meadow. It was Thursday, Sept. 12, 1839. Worcester was a town surrounded by farms, and its small community of free people of color mostly lived in Pine Meadow. In Pine Meadow, the two men posing as Palmer merchants knocked on Fanny Proctor's door and asked for one of her boys. Samuel Johnson later recalled the unfamiliar white men asking him the same question.

One of the men, Elias Turner, had been spotted a few days before in Shirley asking local officials there if he might employ a black boy from the town's poor house. The overseer of the poor sent Mr. Turner away empty handed. But in Lunenburg, Caira Hazard had been swayed by a similar offer of employment for her son, Nahum. Two unfamiliar white men had come to her house on Monday, Sept. 2. The strangers said they operated a tavern in Western Massachusetts, about 60 miles away over the mountains. If young Nahum would come work in the tavern, they promised to see to his upkeep and education.

The solicitation wasn't unusual for the times. The men offered a kind of apprenticeship that then was common for poor boys of any race. A local man had vouched, falsely as it turned out, for the two strangers.

As a widow with several children to care for, Mrs. Hazard accepted the offer and allowed Nahum to go with the men. But there was no tavern. The men, in fact, planned to enrich themselves by selling her free born son into bondage in the slave markets of Virginia, and they hoped to get another boy or two before heading south. One of the men who called on Mrs. Hazard was Dickinson Shearer, a former resident of Palmer who had moved away years ago, eventually ending up in Cartersville, Virginia, on the outskirts of Richmond. The other man was likely Francis Wilkinson, a Virginia slave trader.

Ten days later, Mr. Shearer and his nephew, Mr. Turner, appeared in Worcester's Pine Meadow posing as shopkeepers. They didn't have Nahum Hazard with them at the time. It's not clear where they had stashed the boy. The kidnappers eventually found their way to the home of John and Diana Francis, members of Worcester's small black community. Mrs. Francis heard men outside speaking to her 8 year old son, Sidney, and went out to see what they wanted. Mr. Shearer launched into his pitch, claiming he had a store in Palmer selling goods from England and the West Indies. He said young Sidney looked to be a smart lad and offered to take him on in the shop. He promised to send the boy to school in the summer when there was less work to do.

"He said he wanted him to do chores and light work about the house and store, and take care of a horse," Mrs. Francis later recalled in court. Mr. Turner said he'd write with news of Sidney and that, at any rate, the railroad would soon reach Palmer, so Mr. and Mrs. Francis could visit easily. Mrs. Francis sent the men to where her husband was working nearby at a railroad depot. After conversing with the men a while, John Francis gave his consent. He took down the men's names in his account book, but he'd later learn both gave false identities. An hour and a half after they had arrived at the Francis home, Shearer and Turner departed with Sidney in tow.

Something in the arrangement or the demeanor of the men apparently left Mr. Francis feeling unsettled. After asking around for a few days, he set off for Palmer on foot on Sunday, Sept. 15, with $3 in his pocket. He would end up being away for nearly two weeks trying to pick up the men's trail after finding no trace of them in Palmer. As Mr. Francis walked west that Sunday, his son and Nahum already had been taken more than 400 miles from Worcester. The boys had nearly reached Fredericksburg, Virginia, in a series of stagecoaches, steam boats and trains.

In Fredericksburg, one or both of the boys created a commotion by asking for a book to pass the time and reading aloud from advertisements posted in a barbershop. Word of the supposed slave boys who could read, an implausibility in the South of the day, eventually reached the ears of J.P. Lipscomb, a local man who correctly sniffed out the unfolding kidnapping. By that time, the boys had been taken to Richmond and then on to Cartersville by Francis Wilkinson. Mr. Wilkinson likely had been the man who visited the Hazard home in Lunenburg with Mr. Shearer.

Mr. Lipscomb soon showed up in Cartersville with a constable and demanded to speak to the boys. Sidney was found in Mr. Wilkinson's cellar. The boy told Mr. Lipscomb and the constable he was from Worcester and that his parents had only consented for him to go a short distance away. The constable arrested Mr. Wilkinson and Mr. Shearer and took them and Sidney back to Fredericksburg to sort the matter out. It's not clear if Nahum went with them that day or followed later.

A letter explaining the situation written by Fredericksburg Mayor Benjamin Clark arrived in Worcester on Thursday, Sept. 19, a week after Sidney had been taken. The town was in an uproar. News of the kidnappings roiled Worcester from the modest homes of Pine Meadow to the wealthy white households along Elm Street. Levi Newton, nephew of former governor Levi Lincoln, struck an indignant tone writing in his personal diary that Sunday. "Today I hear of an outrageous case of stealing a negro boy from this town," Mr. Newton wrote.

Two days later, George and Benjamin Rice of Worcester left for Fredericksburg having been assigned to fetch Sidney and one of the prisoners, Mr. Shearer. A man from Lunenburg already in Virginia on business was tasked with bringing Nahum home. Mr. Turner was arrested in Palmer.

The Massachusetts Spy newspaper printed an account of the kidnapping in which the writer noted the tumult gripping the town: "The circumstance has produced a strong sensation here, and much indignation is felt at the commission of so daring an outrage."

As Worcester fumed, Mrs. Hazard in Lunenburg still had no idea what had become of her son. She had fretted for his safety since hearing of Sidney's disappearance from Worcester.

On Thursday, Sept. 26, George Bradburn of Boston arrived in Lunenburg to investigate the circumstances of Nahum's abduction. It was the boy's 9th birthday. Mrs. Hazard recounted to the Bostonian the story she had been told about her son going to work in a tavern. "The mother had no further knowledge of him till I informed her that he was in Richmond, Va., having been rescued from the hands of kidnappers," Mr. Bradburn reported in his account.

"Joy enough, I assure you, was diffused through the bosom of this mother when I assured her that her son was safe, and would soon be restored to her arms again," he wrote.

Mr. Wilkinson, the Virginian, was charged with Nahum's kidnapping but escaped from jail in Richmond that December before he could be brought to Massachusetts to stand trial. Shearer and Turner were tried in the Worcester Court of Common Pleas in Lincoln Square on Jan. 23, 1840. Col. Pliny Merreck, the prosecutor, said it was obvious to anyone that Shearer was guilty of kidnapping and scheming to sell free people into slavery. In his closing arguments, Col. Merreck sought to convince the jury that his nephew and accomplice, Mr. Turner, was equally culpable.

"We found him going with Shearer in quest of colored boys, making that the first subject of inquiry whereever they went until they succeeded," Col. Merreck reminded the jury. The jurors deliberated less than an hour before returning guilty verdicts. They recommended Mr. Turner receive mercy. Mr. Shearer was sentenced to seven years of hard labor, and his name was lost to history after the trial.

Sidney Francis died of tuberculosis in March 1850 at age 19. Nothing is known of his life after he returned to Worcester. His father, John Francis, helped jeer and pelt fugitive slave hunter Asa Butman in 1854 as part of an angry mob that gathered in Worcester to shoo the unwanted visitor out of town. The incident came to be known as the Butman Riot.

Nahum Hazard later returned to the South as a soldier in the Union Army. He was assigned to the 55th Massachusetts Infantry, the second of the so called colored regiments mustered from black and mixed race volunteers. Pvt. Hazard was wounded in November 1864 at the Battle of Honey Hill near Grahamville, South Carolina.

After the war, he returned to northern Worcester County. One of his descendants in the area, Beverly Monroe, 86, of Leominster, recalls hearing family stories about her notable great-grandfather when she was a young woman. Mrs. Monroe said her grandmother, Catherine Thomas Hazard, was one of Nahum Hazard's daughters. Mrs. Monroe wrote a fictional account of the kidnapping of her great-grandfather told from the perspective of the boy's mother, Caira Hazard.

"I tried to picture the terrible travail of waiting all those weeks for word of him," Mrs. Monroe said. "As a mother, I'm so sympathetic to that. I can't image one of my sons being taken off." Mrs. Monroe said she has always been moved by the notion that, in a sense, her great-grandfather was saved from slavery by education. "He knew how to read, and that was unusual for the boys in the South who were slaves, the poor things," she said. "In those days, slavers were capturing people willy-nilly and most of them didn't escape."

Musician and playwright Dillon Bustin of Marshfield was inspired by the story to begin writing a series of musicals based on the extraordinary life of Mr. Hazard. "He left nothing in the way of personal expression that I'm aware of, no letters," Mr. Bustin said. "But he was a survivor. He was highly adaptable."

Seventy-four years to the day after he had been abducted, Mr. Hazard died in Leominster on Sept. 2, 1913. He was a few weeks shy of 84 years old.

Nahum Gardner Hazard is buried on a shady edge of Townsend's Hillside Cemetery, next to his wife, Harriet, and three of their children who died young. On the small tombstone commemorating an 8-month-old girl named Helen and an unnamed infant son, the grieving parents had these words chiseled: "Sleep on dear babes and take your rest."

Source: Telegram Gazette, Thomas Caywood (Feb. 10, 2014 edition)

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter