Columbus Ohio's First African American Aviator

Edward Elder Cooper

Samuel R. Lowery: First Black Lawyer to Argue a C…

Frederick Douglass

Henry Lee Price

James E Reed

William Monroe Trotter

Matthew Anderson

Dr. William A 'Bud' Burns

Orrin C Evans

Wendell Phillips Dabney

Robert H McNeill

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Mr. Hendricks

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

Michael Francis Blake

Robert J Wilkinson

G. Grant Williams

William Still

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

Hugh M Burkett

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazar…

Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

James Alexander Chiles

Randolph Miller

Earliest Sit-Ins

A Pioneer Aviator: Emory Conrad Malick

Louis Charles Roudanez

Our Composite Nationality: An 1869 Speech by Frede…

Building His Destiny

William C Goodridge

No Justice Just Grief: What Happened in Groveland

The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll

Trouble in Levittown

A Town Called Africville

Justice Delayed Justice Denied

Platt Family

Brave Heart

Exodusters

Portland to Peaks Winner of 1927

The Rhinelander Trial

Hiding in Plain Sight: The Johnston Family

Unfair Grounds

Camp Nizhoni

Eyes Magazine

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

38 visits

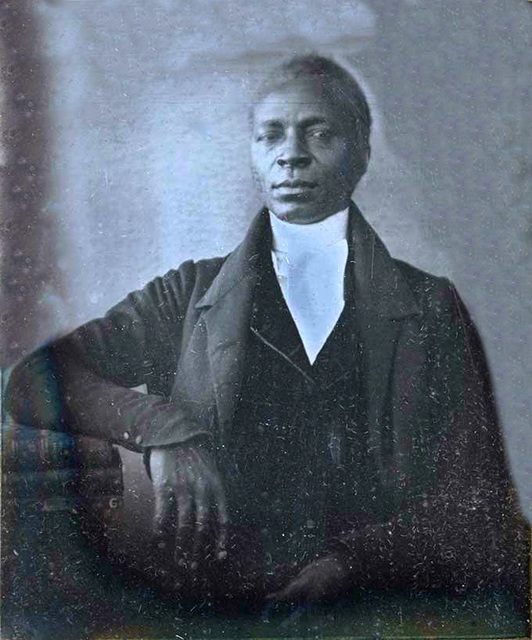

James Forten

This circa 1840 sixth plate daguerreotype is thought to be James Forten (1766-1842). It was in an exhibit which ran from May 22nd through August 9th, 2015. It was titled, 'Many Thousand Gone,' co-curated by Associate Professor of History William Hart and students in his Spring 2015 African American History course. The exhibit consisted of nearly 100 photographs generously loaned to the Middlebury Museum in Vermont by George R. Rinhart, a private collector, of Palm Springs, California. The exhibit takes its title from a 'sorrow song' dating from the Civil War sung by black Union soldiers and freedmen and women. The lyrics to its opening stanza are:

No more auction block for me,

No more, no more;

No more auction block for me;

Many thousand gone

James Forten was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to free parents, Thomas and Sarah Forten on September 2, 1766.

At the age of fourteen, Forten volunteered for service in the Revolutionary War. Assigned to the Royal Lewis, a privateer that supported the Continental Navy, he worked various posts, including powder boy and sailor. Captured by the British on his second cruise, he escaped sale into slavery in the West Indies by winning the friendship of the British captain, who made Forten a companion for his young son. Choosing imprisonment rather than allegiance to Britain, Forten then spent seven long months on a British prison ship. Freed in a prisoner exchange in 1782, he returned to Philadelphia, and to a mother and sister who had both believed him dead.

After the war, Forten spent a year working in shipyards and sail lofts along the River Thames in England. Returning to Philadelphia, he rejoined Robert Bridges sail loft as an apprentice sailmaker, and rose steadily through the ranks. In 1798 Bridges decided to retire and asked the thirty-two-year-old Forten to remain in charge of the loft. He then loaned him enough money to purchase the business. Within three years Forten owned it outright.

Forten had been experimenting with different types of sails for many years. By the early 1800s he had invented one that enabled ships to maneuver more adeptly and to maintain greater speeds. Although he did not patent the sail, he was able to benefit financially, as his sail loft became one of the most successful and prosperous in Philadelphia.

In the early 1800s Forten presided over an integrated workforce of at times more than thirty men, who obeyed his strict rules of hard work, church attendance, abstention from alcohol, and strict punctuality. At times he noted sarcastically that although legally entitled to vote, he was prevented by whites from exercising this right. A shrewd investor, he bought up houses and land in Philadelphia and the surrounding region, purchased stock in the Mount Carbon Rail Company, and made loans to a variety of local businessmen - both black and white.

His fortune was considerable for any man, black or white. While Forten had a luxurious life-style, he also used his financial resources for humanitarian causes. He used more than half of his wealth to purchase the freedom of slaves, finance William Garrison's abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, operate an Underground Railroad station out of his home on Lombard Street, and fund a school he had opened for black children in his house.

Forten worked closely with other antislavery leaders, such as Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, and was a founding member of the Free African Society and the American Reform Society. Vocal in his opposition to slavery, he was also active in other reform causes, particularly women's rights and temperance, and was involved in almost every major civic event concerning the African American community in Philadelphia from the 1790s until his death in 1842. Indecisive on the question of colonization - a popular plan to resettle free blacks in Africa - he became a firm opponent and refused offers that he set an example by leaving the country.

Forten married Charlote Vandine and together they raised eight children. Unable to enroll their children in schools of their choice, he hired tutors to educate them. In 1833, Forten, his wife and three of their daughters (Margaretta, Harriet, and Sarah), helped to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, the first integrated women's abolitionist organization. Two daughters, Harriet and Sarah, married abolitionist brothers Joseph and Robert Purvis, respectively, and spoke out in favor of abolition and black suffrage.

As a successful African American businessman and civic leader, James Forten for many years personified the American Revolution's ideals of equality and opportunity. In the early 1800s, however, race relations in Pennsylvania, as elsewhere in the nation, deteriorated. In the state's 1838 constitution African American men lost the right to vote in Pennsylvania; at the same time, slave catchers from the South terrorized free blacks, and competition for jobs and housing in Philadelphia led to hostility and violence.

Forten received repeated threats on his life, and in 1834 whites attacked and almost killed his son on the streets of Philadelphia. As King Cotton reinvigorated slave-holding in the American South, the promise of economic opportunity and social harmony between the races in Pennsylvania gave way to restricted economic opportunities and loss of the rights and privileges of citizenship for blacks.

James Forten died on March 4, 1842 at the age of seventy-six.

Source: A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten by Julie Winch

No more auction block for me,

No more, no more;

No more auction block for me;

Many thousand gone

James Forten was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to free parents, Thomas and Sarah Forten on September 2, 1766.

At the age of fourteen, Forten volunteered for service in the Revolutionary War. Assigned to the Royal Lewis, a privateer that supported the Continental Navy, he worked various posts, including powder boy and sailor. Captured by the British on his second cruise, he escaped sale into slavery in the West Indies by winning the friendship of the British captain, who made Forten a companion for his young son. Choosing imprisonment rather than allegiance to Britain, Forten then spent seven long months on a British prison ship. Freed in a prisoner exchange in 1782, he returned to Philadelphia, and to a mother and sister who had both believed him dead.

After the war, Forten spent a year working in shipyards and sail lofts along the River Thames in England. Returning to Philadelphia, he rejoined Robert Bridges sail loft as an apprentice sailmaker, and rose steadily through the ranks. In 1798 Bridges decided to retire and asked the thirty-two-year-old Forten to remain in charge of the loft. He then loaned him enough money to purchase the business. Within three years Forten owned it outright.

Forten had been experimenting with different types of sails for many years. By the early 1800s he had invented one that enabled ships to maneuver more adeptly and to maintain greater speeds. Although he did not patent the sail, he was able to benefit financially, as his sail loft became one of the most successful and prosperous in Philadelphia.

In the early 1800s Forten presided over an integrated workforce of at times more than thirty men, who obeyed his strict rules of hard work, church attendance, abstention from alcohol, and strict punctuality. At times he noted sarcastically that although legally entitled to vote, he was prevented by whites from exercising this right. A shrewd investor, he bought up houses and land in Philadelphia and the surrounding region, purchased stock in the Mount Carbon Rail Company, and made loans to a variety of local businessmen - both black and white.

His fortune was considerable for any man, black or white. While Forten had a luxurious life-style, he also used his financial resources for humanitarian causes. He used more than half of his wealth to purchase the freedom of slaves, finance William Garrison's abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, operate an Underground Railroad station out of his home on Lombard Street, and fund a school he had opened for black children in his house.

Forten worked closely with other antislavery leaders, such as Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, and was a founding member of the Free African Society and the American Reform Society. Vocal in his opposition to slavery, he was also active in other reform causes, particularly women's rights and temperance, and was involved in almost every major civic event concerning the African American community in Philadelphia from the 1790s until his death in 1842. Indecisive on the question of colonization - a popular plan to resettle free blacks in Africa - he became a firm opponent and refused offers that he set an example by leaving the country.

Forten married Charlote Vandine and together they raised eight children. Unable to enroll their children in schools of their choice, he hired tutors to educate them. In 1833, Forten, his wife and three of their daughters (Margaretta, Harriet, and Sarah), helped to found the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, the first integrated women's abolitionist organization. Two daughters, Harriet and Sarah, married abolitionist brothers Joseph and Robert Purvis, respectively, and spoke out in favor of abolition and black suffrage.

As a successful African American businessman and civic leader, James Forten for many years personified the American Revolution's ideals of equality and opportunity. In the early 1800s, however, race relations in Pennsylvania, as elsewhere in the nation, deteriorated. In the state's 1838 constitution African American men lost the right to vote in Pennsylvania; at the same time, slave catchers from the South terrorized free blacks, and competition for jobs and housing in Philadelphia led to hostility and violence.

Forten received repeated threats on his life, and in 1834 whites attacked and almost killed his son on the streets of Philadelphia. As King Cotton reinvigorated slave-holding in the American South, the promise of economic opportunity and social harmony between the races in Pennsylvania gave way to restricted economic opportunities and loss of the rights and privileges of citizenship for blacks.

James Forten died on March 4, 1842 at the age of seventy-six.

Source: A Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten by Julie Winch

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter