Henry Bibb

The Inalienable Right to be Free

Jim Hercules

Freedom with the Joneses

Sara Baro Colcher

George O. Brown

John Dabney

Letter from a Freed Man: Jourdan Anderson

Siah Hulett Carter: Escape on the Monitor

Ruth Cox Adams

Ellen Craft

No Longer Hidden

The Woman Who Escaped Enslavement by President Geo…

George W Lowther

Edmondson Sisters

The Truth's Daughter

Please Hear Our Prayers

Caldonia Fackler 'Cal' Johnson

Nancy Green

The Gardners

3X Great Grandson Remembers

Frederick Foote, Sr.

Samuel Harper and Jane Hamilton

Sylvia Conner

Mary Jane Conner

The Freeman Girls

Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazar…

Hugh M Burkett

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

William Still

G. Grant Williams

Robert J Wilkinson

Michael Francis Blake

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

Mr. Hendricks

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Robert H McNeill

Wendell Phillips Dabney

Orrin C Evans

Dr. William A 'Bud' Burns

Matthew Anderson

William Monroe Trotter

James E Reed

Henry Lee Price

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

37 visits

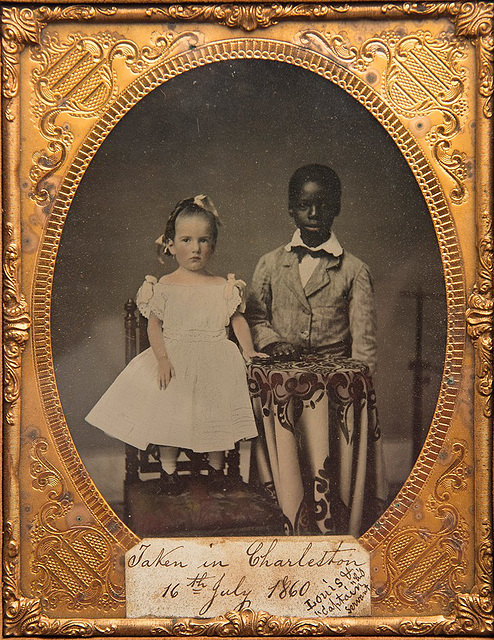

Captured Faces

Louis & "Captain" Servant photographed in Charleston, South Carolina on July 16, 1860.

The history of American photography starts in Philadelphia in the 1830s when it was used by medical researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Within decades of its introduction, photography swiftly became a transformative tool that was powerfully used in politics and society.

In the contentious political climate of the late antebellum era, photographs of the enslaved gave slaveholders a powerful new evidentiary tool to envision and perform a benevolent and intimate regime. Through the circulation and display of images of well-dressed bondspeople and portraits of enslaved caretakers with white children, enslavers projected a comfortable, harmonious, and familial form of bondage, which purportedly treated its laborers as people, not commodities. In the late antebellum era, slave photographs and their attendant photographic practices emerged as a key means for enslavers to persuade themselves and others of the just and beneficial nature of slavery.

Matthew Fox-Amato’s examination of its early influence in “Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America” (Oxford; $39.95) features over 100 color illustrations — including little-studied photographs of slaves, ex-slaves, free African Americans and abolitionists.

Fox-Amato, an assistant professor of history at the University of Idaho, offers rare photographs to create a center of understanding enslavement and the Civil War. From the earliest days of the medium, photos of whites and Blacks, free and enslaved, before and during the Civil War documented 19th-century America.

“Exposing Slavery takes a fresh look at the role of photography in ‘humanizing’ the institution of chattel slavery,” notes Tina Campt, author of “Listening to Images.” “Revisiting the archive of slave photography that haunts contemporary representations of the subjection of black bodies in the 21st century, the book complicates our understanding of the subjects of these images at a moment when digital imaging has become one of the most important tools in the ongoing battle against anti-Black violence. The book provides a significant rebuttal to any assertion that these historical images are simply a reflection of mastery or submission. It tells a very different story that challenges us to look more closely at this troubling and insightful archive.”

Formerly enslaved-turned-abolitionist Frederick Douglass was an early fan of the daguerreotype, an early type of photo, writing four speeches on the medium and sitting for at least 160 portraits during his lifetime.

Slave owners made the abstractions of “slavery” and “mastery” concrete through miniature photographic depictions and social performances. They constructed and enacted a benevolent, intimate form of slavery for themselves and those in their social circles, one that implicitly and explicitly rejected the notion that slaves were viewed and treated as commodities. But slave photography actually constituted a precarious tool of power for southern slaveholders. A photographic portrait also made claims about the identity of the enslaved sitter. The very same portraiture conventions used to convey a humane form of bondage simultaneously implied the individuality and subjectivity of the enslaved sitter at least in theory. This was the bargain slaveholders made, consciously or not, when commissioning slave portraits. Elevating favored slaves helped owners to rationalize bondage and to perform a benevolent form of mastery, but elevating the slave too much imperiled the ideological foundations of their world. How slaveholders dealt with the implications of slave portraits is partially revealed in written records. Rare diary entries, private letters, and paper notes attached to photograph cases reveal how southern whites articulated what slave photographs conveyed and confirmed. Time and time again, slaveholders sought to define, undercut, and limit slaves’ expressions of humanity. Photography created a venue that cast enslavers as the arbiters of enslaved people’s social identities.

The conflicts over human bondage ultimately reshaped the nation, and in turn, altered a scientific curiosity into a political tool that still impacts society today.

Sources: Exposing Slavery shows human bondage amid visual politics article written by Bobbi Booker Tribune Staff Writer (April 2019); Captured Faces: Why did slaveholders have photographs taken of their slaves, article written by Matthew Fox-Amato (April 2019), Lapham's Quarterly; Louis Manigault & Captain, The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina, charlestonmuseum. org.

The history of American photography starts in Philadelphia in the 1830s when it was used by medical researchers at the University of Pennsylvania. Within decades of its introduction, photography swiftly became a transformative tool that was powerfully used in politics and society.

In the contentious political climate of the late antebellum era, photographs of the enslaved gave slaveholders a powerful new evidentiary tool to envision and perform a benevolent and intimate regime. Through the circulation and display of images of well-dressed bondspeople and portraits of enslaved caretakers with white children, enslavers projected a comfortable, harmonious, and familial form of bondage, which purportedly treated its laborers as people, not commodities. In the late antebellum era, slave photographs and their attendant photographic practices emerged as a key means for enslavers to persuade themselves and others of the just and beneficial nature of slavery.

Matthew Fox-Amato’s examination of its early influence in “Exposing Slavery: Photography, Human Bondage, and the Birth of Modern Visual Politics in America” (Oxford; $39.95) features over 100 color illustrations — including little-studied photographs of slaves, ex-slaves, free African Americans and abolitionists.

Fox-Amato, an assistant professor of history at the University of Idaho, offers rare photographs to create a center of understanding enslavement and the Civil War. From the earliest days of the medium, photos of whites and Blacks, free and enslaved, before and during the Civil War documented 19th-century America.

“Exposing Slavery takes a fresh look at the role of photography in ‘humanizing’ the institution of chattel slavery,” notes Tina Campt, author of “Listening to Images.” “Revisiting the archive of slave photography that haunts contemporary representations of the subjection of black bodies in the 21st century, the book complicates our understanding of the subjects of these images at a moment when digital imaging has become one of the most important tools in the ongoing battle against anti-Black violence. The book provides a significant rebuttal to any assertion that these historical images are simply a reflection of mastery or submission. It tells a very different story that challenges us to look more closely at this troubling and insightful archive.”

Formerly enslaved-turned-abolitionist Frederick Douglass was an early fan of the daguerreotype, an early type of photo, writing four speeches on the medium and sitting for at least 160 portraits during his lifetime.

Slave owners made the abstractions of “slavery” and “mastery” concrete through miniature photographic depictions and social performances. They constructed and enacted a benevolent, intimate form of slavery for themselves and those in their social circles, one that implicitly and explicitly rejected the notion that slaves were viewed and treated as commodities. But slave photography actually constituted a precarious tool of power for southern slaveholders. A photographic portrait also made claims about the identity of the enslaved sitter. The very same portraiture conventions used to convey a humane form of bondage simultaneously implied the individuality and subjectivity of the enslaved sitter at least in theory. This was the bargain slaveholders made, consciously or not, when commissioning slave portraits. Elevating favored slaves helped owners to rationalize bondage and to perform a benevolent form of mastery, but elevating the slave too much imperiled the ideological foundations of their world. How slaveholders dealt with the implications of slave portraits is partially revealed in written records. Rare diary entries, private letters, and paper notes attached to photograph cases reveal how southern whites articulated what slave photographs conveyed and confirmed. Time and time again, slaveholders sought to define, undercut, and limit slaves’ expressions of humanity. Photography created a venue that cast enslavers as the arbiters of enslaved people’s social identities.

The conflicts over human bondage ultimately reshaped the nation, and in turn, altered a scientific curiosity into a political tool that still impacts society today.

Sources: Exposing Slavery shows human bondage amid visual politics article written by Bobbi Booker Tribune Staff Writer (April 2019); Captured Faces: Why did slaveholders have photographs taken of their slaves, article written by Matthew Fox-Amato (April 2019), Lapham's Quarterly; Louis Manigault & Captain, The Charleston Museum, Charleston, South Carolina, charlestonmuseum. org.

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter