Michael Francis Blake

Robert J Wilkinson

G. Grant Williams

William Still

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

Hugh M Burkett

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazar…

Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

The Freeman Girls

Mary Jane Conner

Sylvia Conner

Captured Faces

Henry Bibb

The Inalienable Right to be Free

Jim Hercules

Freedom with the Joneses

Sara Baro Colcher

George O. Brown

John Dabney

Letter from a Freed Man: Jourdan Anderson

Siah Hulett Carter: Escape on the Monitor

Ruth Cox Adams

Ellen Craft

Mr. Hendricks

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Robert H McNeill

Wendell Phillips Dabney

Orrin C Evans

Dr. William A 'Bud' Burns

Matthew Anderson

William Monroe Trotter

James E Reed

Henry Lee Price

Frederick Douglass

Samuel R. Lowery: First Black Lawyer to Argue a C…

Edward Elder Cooper

Columbus Ohio's First African American Aviator

James Forten

James Alexander Chiles

Randolph Miller

Earliest Sit-Ins

A Pioneer Aviator: Emory Conrad Malick

Louis Charles Roudanez

Our Composite Nationality: An 1869 Speech by Frede…

Building His Destiny

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

44 visits

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

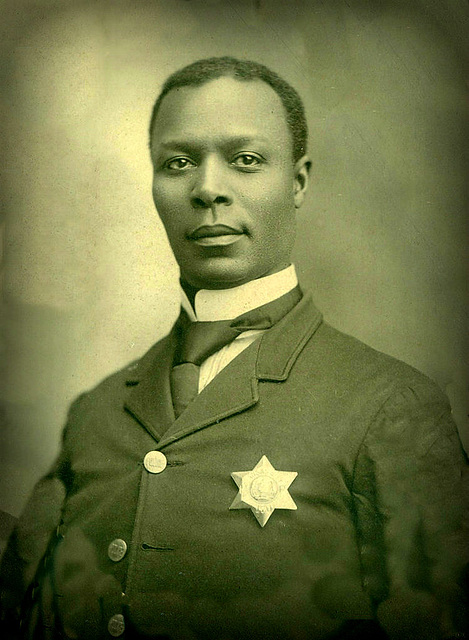

Here Tillman appears in uniform when he was with the Kansas City Police Department.

Born during slavery on March 15, 1858 in Evansville, Indiana, Lafayette Alonzo Tillman would be fortunate not to experience the harshness of the peculiar institution less than 100 miles away to the “South” in the state of Kentucky. Evansville was one of a number of gateway cities in Indiana that provided access to the Underground Railroad, assisting runaway slaves with food, shelter and safe passage to Canada. Information about Tillman’s childhood is fragmented, but there are a number of reflections accounting the death of his father when Tillman was five years old, as well as an assessment of his academic success within the public school system of Indiana. What is more, Tillman’s abilities and scholastic achievements provided him with the foundation he would need in pursuit of a college education at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, and at Wayland Seminary School in Washington, D.C.

At Wayland, Tillman studied theology in preparation to become a Baptist minister, while simultaneously developing his musical talent as a singer. Professor James Storum, the African American educator who became the first principal at Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute in 1883, encouraged this ability. By the late 1870s, Tillman’s strength as a bass soloist and his virtuous nature attracted a number of prominent singing groups ready to take advantage of his rich voice and his gentlemanly decorum. African American singing groups such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers and the Tuskegee Institute Choir entertained both blacks and whites, and served as nationally and internationally recognized ambassadors who educated white patrons about African American culture through song and intimate interactions.

Performing with the New Orleans University Singers and the Donovan Tennesseeans of Philadelphia, Tillman was provided a number of opportunities to tour the eastern and midwestern United States, as well as Europe. (In 1884, in the “Blue Room” at the White House, Tillman and his New Orleans University Singers performed for then-President of the United States, Grover Cleveland. In the special program, Tillman performed his solo “The Laughing Song.”) In 1880, while traveling through the Midwest and performing at both black and white churches, Tillman and the Tennesseeans performed in Kansas City, where his proficiency as a singer gained him local fame as an entertainer. Tillman’s apparent fondness for the growing town and its 7,914 African Americans prompted his move to Kansas City. In 1881 he began a career as an entrepreneur, opening a restaurant at 105 East 12th Street, in the heart of the African American community.

By 1896, Tillman had married Amy Dods of St. Louis, Missouri, closed his restaurant, opened his own barber shop and had begun pursuing his interest in law at Kansas City Law School. The 1890s are recognized as the beginning of segregation in America. Blacks in general and black men in particular were being lynched at a rate of 100 per year. Thus the ideological foundation of Jim Crow in the United States served to shape the experiences of a majority of black men and women within the nation’s imagined borders.

In 1898 Tillman achieved the rank of Quarter-Master Sergeant in Company “K” of the 7th Regiment of the United States Volunteers. He was never deployed to the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, but nevertheless demonstrated his commitment to excellence as a soldier. This would be accounted for by his superior officers who had full faith in his abilities and recognized and applauded his outstanding leadership qualities. This was a turning point for Tillman’s career. Indeed, because of his commitment to excellence he would be honored by the Aurora Democratic Club of Kansas City, which boasted a membership roster that included Alderman James Pendergast, brother of future Kansas City “Boss,” Tom Pendergast. Acknowledging Tillman’s achievements, the Aurora Democratic Club presented the Sergeant with a uniform and an engraved sword which is inscribed: “Presented to Lieutenant L.A. Tillman/49th Regt/In recognition of his high personal character and fidelity to principle by his Kansas City friends and fellow members of Aurora Democratic Club.” The local recognition would secure Tillman’s future in Kansas City, and contribute to his future success in the military.

During the 1899 “Filipino Insurrection” by citizens of the Philippines against U.S. rule, Tillman received an appointment as First Lieutenant of the Forty-Ninth Volunteer Infantry from President William McKinley. Tillman would likely have been stationed in Manila at the same time as Lieutenant Charles Young, the third African American graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point, and before World War I the highest ranked African American solider in the US military. After serving two years in Luzon in the Philippines, Tillman was honorably discharged and he returned to Kansas City.

Tillman’s life and career both refuted and denied any notion of black inferiority and ineptitude. Having gained and maintained a reputation for loyalty, bravery and respectability, Tillman’s connections to influential white Kansas Citians provided him with the needed recommendations to qualify him to the Board of Police Commissioners as a worthy police officer candidate. He was the third black police officer to serve in the Kansas City Police force, after William F. Davis and Robert Alexander. He served with distinction from 1903 until his death in 1914 [from chronic intestinal nephritis]. The range of contributions made by Tillman through his public presence and authority, as well as the degree to which his representation of black potentiality and respectability accelerated the future development of the African American community in Kansas City, has yet to be fully understood.

He and his wife (Amy L Tillman, 1863 - 1943), are buried in Highland Cemetery, Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri.

Bio: Pellom McDaniels I, PhD., Assistant Professor of History and American Studies, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Photo: Lafayette Alonzo Tillman Collection at the Kansas City Museum

Born during slavery on March 15, 1858 in Evansville, Indiana, Lafayette Alonzo Tillman would be fortunate not to experience the harshness of the peculiar institution less than 100 miles away to the “South” in the state of Kentucky. Evansville was one of a number of gateway cities in Indiana that provided access to the Underground Railroad, assisting runaway slaves with food, shelter and safe passage to Canada. Information about Tillman’s childhood is fragmented, but there are a number of reflections accounting the death of his father when Tillman was five years old, as well as an assessment of his academic success within the public school system of Indiana. What is more, Tillman’s abilities and scholastic achievements provided him with the foundation he would need in pursuit of a college education at Oberlin College in Oberlin, Ohio, and at Wayland Seminary School in Washington, D.C.

At Wayland, Tillman studied theology in preparation to become a Baptist minister, while simultaneously developing his musical talent as a singer. Professor James Storum, the African American educator who became the first principal at Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute in 1883, encouraged this ability. By the late 1870s, Tillman’s strength as a bass soloist and his virtuous nature attracted a number of prominent singing groups ready to take advantage of his rich voice and his gentlemanly decorum. African American singing groups such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers and the Tuskegee Institute Choir entertained both blacks and whites, and served as nationally and internationally recognized ambassadors who educated white patrons about African American culture through song and intimate interactions.

Performing with the New Orleans University Singers and the Donovan Tennesseeans of Philadelphia, Tillman was provided a number of opportunities to tour the eastern and midwestern United States, as well as Europe. (In 1884, in the “Blue Room” at the White House, Tillman and his New Orleans University Singers performed for then-President of the United States, Grover Cleveland. In the special program, Tillman performed his solo “The Laughing Song.”) In 1880, while traveling through the Midwest and performing at both black and white churches, Tillman and the Tennesseeans performed in Kansas City, where his proficiency as a singer gained him local fame as an entertainer. Tillman’s apparent fondness for the growing town and its 7,914 African Americans prompted his move to Kansas City. In 1881 he began a career as an entrepreneur, opening a restaurant at 105 East 12th Street, in the heart of the African American community.

By 1896, Tillman had married Amy Dods of St. Louis, Missouri, closed his restaurant, opened his own barber shop and had begun pursuing his interest in law at Kansas City Law School. The 1890s are recognized as the beginning of segregation in America. Blacks in general and black men in particular were being lynched at a rate of 100 per year. Thus the ideological foundation of Jim Crow in the United States served to shape the experiences of a majority of black men and women within the nation’s imagined borders.

In 1898 Tillman achieved the rank of Quarter-Master Sergeant in Company “K” of the 7th Regiment of the United States Volunteers. He was never deployed to the Philippines during the Spanish-American War, but nevertheless demonstrated his commitment to excellence as a soldier. This would be accounted for by his superior officers who had full faith in his abilities and recognized and applauded his outstanding leadership qualities. This was a turning point for Tillman’s career. Indeed, because of his commitment to excellence he would be honored by the Aurora Democratic Club of Kansas City, which boasted a membership roster that included Alderman James Pendergast, brother of future Kansas City “Boss,” Tom Pendergast. Acknowledging Tillman’s achievements, the Aurora Democratic Club presented the Sergeant with a uniform and an engraved sword which is inscribed: “Presented to Lieutenant L.A. Tillman/49th Regt/In recognition of his high personal character and fidelity to principle by his Kansas City friends and fellow members of Aurora Democratic Club.” The local recognition would secure Tillman’s future in Kansas City, and contribute to his future success in the military.

During the 1899 “Filipino Insurrection” by citizens of the Philippines against U.S. rule, Tillman received an appointment as First Lieutenant of the Forty-Ninth Volunteer Infantry from President William McKinley. Tillman would likely have been stationed in Manila at the same time as Lieutenant Charles Young, the third African American graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point, and before World War I the highest ranked African American solider in the US military. After serving two years in Luzon in the Philippines, Tillman was honorably discharged and he returned to Kansas City.

Tillman’s life and career both refuted and denied any notion of black inferiority and ineptitude. Having gained and maintained a reputation for loyalty, bravery and respectability, Tillman’s connections to influential white Kansas Citians provided him with the needed recommendations to qualify him to the Board of Police Commissioners as a worthy police officer candidate. He was the third black police officer to serve in the Kansas City Police force, after William F. Davis and Robert Alexander. He served with distinction from 1903 until his death in 1914 [from chronic intestinal nephritis]. The range of contributions made by Tillman through his public presence and authority, as well as the degree to which his representation of black potentiality and respectability accelerated the future development of the African American community in Kansas City, has yet to be fully understood.

He and his wife (Amy L Tillman, 1863 - 1943), are buried in Highland Cemetery, Kansas City, Jackson County, Missouri.

Bio: Pellom McDaniels I, PhD., Assistant Professor of History and American Studies, University of Missouri-Kansas City

Photo: Lafayette Alonzo Tillman Collection at the Kansas City Museum

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter