Orrin C Evans

Wendell Phillips Dabney

Robert H McNeill

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Mr. Hendricks

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

Michael Francis Blake

Robert J Wilkinson

G. Grant Williams

William Still

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

Hugh M Burkett

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazar…

Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

The Freeman Girls

Mary Jane Conner

Sylvia Conner

Captured Faces

Henry Bibb

The Inalienable Right to be Free

Jim Hercules

Freedom with the Joneses

Sara Baro Colcher

Matthew Anderson

William Monroe Trotter

James E Reed

Henry Lee Price

Frederick Douglass

Samuel R. Lowery: First Black Lawyer to Argue a C…

Edward Elder Cooper

Columbus Ohio's First African American Aviator

James Forten

James Alexander Chiles

Randolph Miller

Earliest Sit-Ins

A Pioneer Aviator: Emory Conrad Malick

Louis Charles Roudanez

Our Composite Nationality: An 1869 Speech by Frede…

Building His Destiny

William C Goodridge

No Justice Just Grief: What Happened in Groveland

The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll

Trouble in Levittown

A Town Called Africville

Justice Delayed Justice Denied

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

42 visits

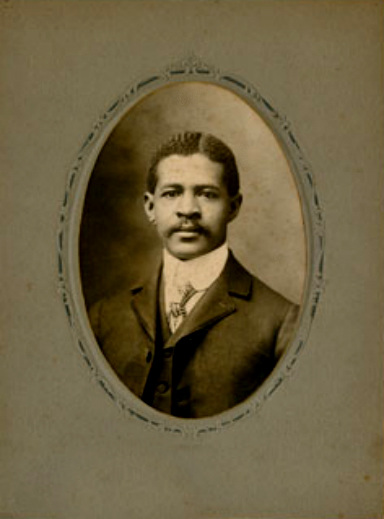

Dr. William A 'Bud' Burns

West Dayton’s historic Wright-Dunbar neighborhood scantly resembles its turn-of-the-century appearance—19th century buildings rest alongside modern storefronts and the rumble of automobiles has long replaced the click-clack of horse hooves on unpaved roads.

But it was here in a late 1880s Italianate-style house at 219 N. Summit St. (now Paul Laurence Dunbar Street) that Dr. William A. “Bud” Burns, Dayton’s first licensed African American doctor, cared for Paul Laurence Dunbar, the world’s first renowned African American poet, as he lay dying of tuberculosis.

Both Burns and Dunbar attended Central High School on Wilkinson and Fourth streets in downtown Dayton. Dunbar was in a small class of 27 students (alongside Orville Wright), and though Burns was a year younger he and Dunbar were two of the only African-American students at Central High. They formed an ineffable bond.

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s story has been told ceaselessly. At a time when racism prevented African Americans from obtaining even the most plebeian positions Dunbar rose as an international literary star. But while Dunbar saw the glare of publicity Burns altered history in his own right.

“William Burns was, in a truer, greater sense than Paul, the friend and leader of his race in Dayton,” wrote author Charlotte Reeve Conover in her 1907 book, Of Some Dayton Saints and Prophets. “Dunbar represented unattainable things; Burns the attainable.”

Losing his parents early in life, Burns was brought up by Capt. Charles B. Stivers, a Civil War veteran, Central High School principal and the namesake of Stivers School for the Arts. And it was Stivers that first encouraged Burns to pursue medicine.

In 1893, Burns studied under Dr. J.C. Reeve of Dayton before paying his way through Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Returning to Dayton he opened his West Fifth Street office caring for patients of all backgrounds, including his childhood friend Paul Laurence Dunbar.

But sadly, in May 1899, after collapsing from pneumonia while giving a reading in New York City, Dunbar began requiring more intensive treatment. Now internationally famous the poet developed tuberculosis; he became dependent on alcohol (prescribed to alleviate his pain) and sought fresh air on distant health retreats before settling back home in Dayton in 1903.

Burns joined Dunbar on one of his health retreats to the Catskill Mountains and he stood by the poet’s side as he struggled to stay alive. But, tragically, it was Burns—not Dunbar—that first met the mercurial hands of death.

After a brief two-week battle with typhoid fever Burns died on Nov. 19, 1905, at the age of 32. “The Dayton Academy of Medicine held a called meeting Sunday afternoon at their quarters in the Ludlow Street Arcade,” wrote the Dayton Evening Herald on Nov. 20, 1905. “No member of the Academy was held in higher esteem than was Dr. Burns.”

Burns’ death not only shocked the medical community but the city of Dayton as a whole. And no one took the news harder than Dunbar. “Paul never seemed to recover from Bud’s death,” wrote author Anne Honious in her book, What Dreams We Have. “A friend noted that after the funeral Dunbar more often seemed discouraged in his fight against tuberculosis.”

Paul Laurence Dunbar died on Feb. 9, 1906, at the age of 33, less than three months after his boyhood friend and doctor, William A. Burns. Both men are buried at Woodland Cemetery and Arboretum in Dayton; Burns in section 33, Dunbar in section 101. Here they lie. Two old friends. Two guiding lights. Reunited in the end.

Source: Dayton Magazine: Doctor to a Poet article by

Leo DeLuca

But it was here in a late 1880s Italianate-style house at 219 N. Summit St. (now Paul Laurence Dunbar Street) that Dr. William A. “Bud” Burns, Dayton’s first licensed African American doctor, cared for Paul Laurence Dunbar, the world’s first renowned African American poet, as he lay dying of tuberculosis.

Both Burns and Dunbar attended Central High School on Wilkinson and Fourth streets in downtown Dayton. Dunbar was in a small class of 27 students (alongside Orville Wright), and though Burns was a year younger he and Dunbar were two of the only African-American students at Central High. They formed an ineffable bond.

Paul Laurence Dunbar’s story has been told ceaselessly. At a time when racism prevented African Americans from obtaining even the most plebeian positions Dunbar rose as an international literary star. But while Dunbar saw the glare of publicity Burns altered history in his own right.

“William Burns was, in a truer, greater sense than Paul, the friend and leader of his race in Dayton,” wrote author Charlotte Reeve Conover in her 1907 book, Of Some Dayton Saints and Prophets. “Dunbar represented unattainable things; Burns the attainable.”

Losing his parents early in life, Burns was brought up by Capt. Charles B. Stivers, a Civil War veteran, Central High School principal and the namesake of Stivers School for the Arts. And it was Stivers that first encouraged Burns to pursue medicine.

In 1893, Burns studied under Dr. J.C. Reeve of Dayton before paying his way through Western Reserve University in Cleveland. Returning to Dayton he opened his West Fifth Street office caring for patients of all backgrounds, including his childhood friend Paul Laurence Dunbar.

But sadly, in May 1899, after collapsing from pneumonia while giving a reading in New York City, Dunbar began requiring more intensive treatment. Now internationally famous the poet developed tuberculosis; he became dependent on alcohol (prescribed to alleviate his pain) and sought fresh air on distant health retreats before settling back home in Dayton in 1903.

Burns joined Dunbar on one of his health retreats to the Catskill Mountains and he stood by the poet’s side as he struggled to stay alive. But, tragically, it was Burns—not Dunbar—that first met the mercurial hands of death.

After a brief two-week battle with typhoid fever Burns died on Nov. 19, 1905, at the age of 32. “The Dayton Academy of Medicine held a called meeting Sunday afternoon at their quarters in the Ludlow Street Arcade,” wrote the Dayton Evening Herald on Nov. 20, 1905. “No member of the Academy was held in higher esteem than was Dr. Burns.”

Burns’ death not only shocked the medical community but the city of Dayton as a whole. And no one took the news harder than Dunbar. “Paul never seemed to recover from Bud’s death,” wrote author Anne Honious in her book, What Dreams We Have. “A friend noted that after the funeral Dunbar more often seemed discouraged in his fight against tuberculosis.”

Paul Laurence Dunbar died on Feb. 9, 1906, at the age of 33, less than three months after his boyhood friend and doctor, William A. Burns. Both men are buried at Woodland Cemetery and Arboretum in Dayton; Burns in section 33, Dunbar in section 101. Here they lie. Two old friends. Two guiding lights. Reunited in the end.

Source: Dayton Magazine: Doctor to a Poet article by

Leo DeLuca

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter