Wendell Phillips Dabney

Robert H McNeill

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Mr. Hendricks

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

Michael Francis Blake

Robert J Wilkinson

G. Grant Williams

William Still

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

Hugh M Burkett

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazar…

Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

The Freeman Girls

Mary Jane Conner

Sylvia Conner

Captured Faces

Henry Bibb

The Inalienable Right to be Free

Jim Hercules

Freedom with the Joneses

Sara Baro Colcher

George O. Brown

Dr. William A 'Bud' Burns

Matthew Anderson

William Monroe Trotter

James E Reed

Henry Lee Price

Frederick Douglass

Samuel R. Lowery: First Black Lawyer to Argue a C…

Edward Elder Cooper

Columbus Ohio's First African American Aviator

James Forten

James Alexander Chiles

Randolph Miller

Earliest Sit-Ins

A Pioneer Aviator: Emory Conrad Malick

Louis Charles Roudanez

Our Composite Nationality: An 1869 Speech by Frede…

Building His Destiny

William C Goodridge

No Justice Just Grief: What Happened in Groveland

The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll

Trouble in Levittown

A Town Called Africville

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

39 visits

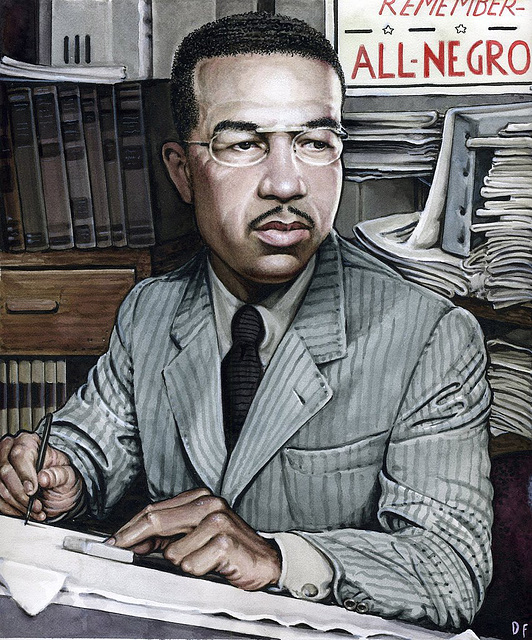

Orrin C Evans

When Orrin C. Evans died in 1971 at the age of 68 he was eulogized in the New York Times as ‘the dean of black reporters’. From our vantage point of another quarter century, we can also say he was the father of black comic books.

Mr Evans was born in 1902 in Steeleton, Pennsylvania, the eldest son of George J. Evans Sr, and Maude Wilson Evans. Mr Evans Sr., was employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad, his wife was the first black person to graduate from the Williamsport Teachers’ College,and the family lived in white neighborhoods. However, despite this stable home life the every day realities of Northern racism were never far from their door. Mr Evans Sr. passed for white in order to provide a better living for his family than the menial jobs available to blacks would allow, but this forced him to carry the pretense to the inevitable ends of hiding the darker skinned Orrin in a back room while Maude donned an apron and pretended to be a maid when friends from his work dropped by. On other occasions, his father was not able to acknowledge Orrin at his workplace. Years later Orrin was visibly moved when relating these episodes. As Orrin’s friend, Claude Lewis wrote in 1971 ‘There was no National Association for the Advancement of Colored People back then, there was no Urban League. Like others of his time, Orrin Evans was out there on his own. And what he had to suffer was more than anyone I know could endure’.

His first job was on the Sportsman’s Magazine at age 17, and his first real newspaper experience was with the Philadelphia Tribune, the oldest black paper in the country. From there, in the early nineteen-thirties, he decided to break the color barrier and landed a writing position on the Philadelphia Record, becoming the first black writer to cover general assignments for a mainstream white newspaper in the United States. In 1944 at the Record he wrote a series of articles about segregation in the armed services, which were read into the congressional record, and helped end the practice. He won an honorable mention in that year’s Hayword Hale Broun award, but also drew some unwelcome attention. To criticize the government during wartime, even to point out the obvious hypocrisy of segregating troops putting their lives on the line to defend a country where democracy supposedly makes all men equal was considered treasonous by some and he and his family received death threats. His daughter Hope remembers their house being protected in a 24 hour a day vigil by a congregation of Orrin’s friends, both black and white, until the threats subsided.

This was not the only time Orrin was threatened because of his color and position. Once at the Philadelphia Police Precinct at 55th and Pine a police sergeant pulled his revolver and ordered him out of the station, not believing a black man had any legitimate place on the front side of the bars, and the national hero and Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh once held up a press conference during the infamous kidnapping of his son to have Orrin ousted because he was black.

For Orrin to note the lack of black heroes in the popular culture was a singular feat in itself. As Claude Lewis said in a recent interview ‘We weren’t very conscious about being left out, it was just the way things were. We identified with Superman, Batman, Submariner and the rest of them without giving much thought to it. If you’ve never seen a black hero you don’t spend a lot of time wondering where they are. Today you would, but back then, there were no blacks in ads. It just didn’t happen’. Orrin wanted to change all this. He considered himself an urban American born in the twentieth century, fully integrated into the western world. He and his wife were long time supporters of the NAACP and the Urban League. The works of WEB Du Bois spoke more to him than did those of Marcus Garvey. He possessed a library said to be possibly the finest in the black community with volumes not only of Afrocentric interest or white commentaries on what was termed ‘the Negro problem’, but a library that represented his own wide range of interests, and he wanted to produce a comic that would reflect these values.

All Negro Comics # 1 carries a cover date of June 1947. No information about the press run or distribution remains, but it is believed that the comic was distributed outside of the Philadelphia area.

A second issue was planned and the art completed, but when Orrin was ready to publish he found that his source for newsprint would no longer sell to him, nor would any of the other vendors he contacted. Though Orrin was unyielding in his support of integration and civil rights he was moderate in his methods of achieving these goals. He believed in the general fairness of the system he had been born into. He was not a man given to conspiratorial thinking, but his family remembers that his belief was that there was pressure being placed on the newsprint wholesalers by bigger publishers and distributors who didn’t welcome any intrusions on their established territories.

Orrin Evans returned to the newspaper business. He was an editor at the Chester Times, and later at the Philadelphia Bulletin, where he worked with Claude Lewis who recently said ‘Orrin had many contacts throughout the city of Philadelphia and the region. He knew the people who were running the city and he knew the people who were at the bottom, and he was equally at ease in either community. He was well liked and well versed and that made him a very valuable person in a newsroom’. During his lifetime Mr Evans was featured in articles in Jet and Ebony magazines. He was a director of the Philadelphia Press Association, and an officer of the Newspaper Guild of Greater Philadelphia. In 1966 he won the Inter Urban League of Pennsylvania Achievement Award. He covered more National Urban League and NAACP conventions than any other reporter and the month before his death he was honored in a resolution at the annual NAACP convention in Minneapolis and a scholarship was created in his name.

Illustration by Drew Friedman

Sources: Interviews Hope Evans Boyd, George J. Evans Jr, Claude Lewis, George Evans. Article Philadelphia Tribune 15 Feb 77, Pg 21: Orrin Evans, A Black Who Refused to Be Bitter.

Entry In Black and White (reference) Pg 306, Obituary NY Times 8 Aug 7, Pg 58, Obituary Philadelphia Bulletin 8 Aug 71

Charles Lindburg reference is from American Swastika by Charles Higham, Doubleday Publishers,1985. Garden City, NY., TomChristopher.com.

Mr Evans was born in 1902 in Steeleton, Pennsylvania, the eldest son of George J. Evans Sr, and Maude Wilson Evans. Mr Evans Sr., was employed by the Pennsylvania Railroad, his wife was the first black person to graduate from the Williamsport Teachers’ College,and the family lived in white neighborhoods. However, despite this stable home life the every day realities of Northern racism were never far from their door. Mr Evans Sr. passed for white in order to provide a better living for his family than the menial jobs available to blacks would allow, but this forced him to carry the pretense to the inevitable ends of hiding the darker skinned Orrin in a back room while Maude donned an apron and pretended to be a maid when friends from his work dropped by. On other occasions, his father was not able to acknowledge Orrin at his workplace. Years later Orrin was visibly moved when relating these episodes. As Orrin’s friend, Claude Lewis wrote in 1971 ‘There was no National Association for the Advancement of Colored People back then, there was no Urban League. Like others of his time, Orrin Evans was out there on his own. And what he had to suffer was more than anyone I know could endure’.

His first job was on the Sportsman’s Magazine at age 17, and his first real newspaper experience was with the Philadelphia Tribune, the oldest black paper in the country. From there, in the early nineteen-thirties, he decided to break the color barrier and landed a writing position on the Philadelphia Record, becoming the first black writer to cover general assignments for a mainstream white newspaper in the United States. In 1944 at the Record he wrote a series of articles about segregation in the armed services, which were read into the congressional record, and helped end the practice. He won an honorable mention in that year’s Hayword Hale Broun award, but also drew some unwelcome attention. To criticize the government during wartime, even to point out the obvious hypocrisy of segregating troops putting their lives on the line to defend a country where democracy supposedly makes all men equal was considered treasonous by some and he and his family received death threats. His daughter Hope remembers their house being protected in a 24 hour a day vigil by a congregation of Orrin’s friends, both black and white, until the threats subsided.

This was not the only time Orrin was threatened because of his color and position. Once at the Philadelphia Police Precinct at 55th and Pine a police sergeant pulled his revolver and ordered him out of the station, not believing a black man had any legitimate place on the front side of the bars, and the national hero and Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh once held up a press conference during the infamous kidnapping of his son to have Orrin ousted because he was black.

For Orrin to note the lack of black heroes in the popular culture was a singular feat in itself. As Claude Lewis said in a recent interview ‘We weren’t very conscious about being left out, it was just the way things were. We identified with Superman, Batman, Submariner and the rest of them without giving much thought to it. If you’ve never seen a black hero you don’t spend a lot of time wondering where they are. Today you would, but back then, there were no blacks in ads. It just didn’t happen’. Orrin wanted to change all this. He considered himself an urban American born in the twentieth century, fully integrated into the western world. He and his wife were long time supporters of the NAACP and the Urban League. The works of WEB Du Bois spoke more to him than did those of Marcus Garvey. He possessed a library said to be possibly the finest in the black community with volumes not only of Afrocentric interest or white commentaries on what was termed ‘the Negro problem’, but a library that represented his own wide range of interests, and he wanted to produce a comic that would reflect these values.

All Negro Comics # 1 carries a cover date of June 1947. No information about the press run or distribution remains, but it is believed that the comic was distributed outside of the Philadelphia area.

A second issue was planned and the art completed, but when Orrin was ready to publish he found that his source for newsprint would no longer sell to him, nor would any of the other vendors he contacted. Though Orrin was unyielding in his support of integration and civil rights he was moderate in his methods of achieving these goals. He believed in the general fairness of the system he had been born into. He was not a man given to conspiratorial thinking, but his family remembers that his belief was that there was pressure being placed on the newsprint wholesalers by bigger publishers and distributors who didn’t welcome any intrusions on their established territories.

Orrin Evans returned to the newspaper business. He was an editor at the Chester Times, and later at the Philadelphia Bulletin, where he worked with Claude Lewis who recently said ‘Orrin had many contacts throughout the city of Philadelphia and the region. He knew the people who were running the city and he knew the people who were at the bottom, and he was equally at ease in either community. He was well liked and well versed and that made him a very valuable person in a newsroom’. During his lifetime Mr Evans was featured in articles in Jet and Ebony magazines. He was a director of the Philadelphia Press Association, and an officer of the Newspaper Guild of Greater Philadelphia. In 1966 he won the Inter Urban League of Pennsylvania Achievement Award. He covered more National Urban League and NAACP conventions than any other reporter and the month before his death he was honored in a resolution at the annual NAACP convention in Minneapolis and a scholarship was created in his name.

Illustration by Drew Friedman

Sources: Interviews Hope Evans Boyd, George J. Evans Jr, Claude Lewis, George Evans. Article Philadelphia Tribune 15 Feb 77, Pg 21: Orrin Evans, A Black Who Refused to Be Bitter.

Entry In Black and White (reference) Pg 306, Obituary NY Times 8 Aug 7, Pg 58, Obituary Philadelphia Bulletin 8 Aug 71

Charles Lindburg reference is from American Swastika by Charles Higham, Doubleday Publishers,1985. Garden City, NY., TomChristopher.com.

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter