Savage Sideshow: Exhibiting Africans as Freaks

Lizzie Shephard

Under Siege

The Port Chicago Explosion and Mutiny

Stevedore --- New Orleans 1885

Pla-Mor Roller Skating Rink

Harlem's Dunbar Bank

Berry & Ross Doll Company

To Protect and Serve

More Than A Difference of Opinion

Burning Death of Henry Smith

Henry Louis Aaron

Elwood Palmer Cooper

Councilman L.O. Payne's All Female Basketball Team

Girls Dance Team

And She's A True Blue Triangle Girl

Lulu White

A Day in the Life of Cake Sellers

Eyes Magazine

Camp Nizhoni

Unfair Grounds

Hiding in Plain Sight: The Johnston Family

The Rhinelander Trial

A Harlem Street

The Baker Family

Nacirema Club Members

Searching for Eugene Williams

Charles Collins: His 1902 Murder Became a Hallmar…

Mrs. A. J. Goode

Hannah Elias: The Black Enchantress Who Was At One…

Call and Post Newsboys

Wrightsville Survivors

Martha Peterson: Woman in the Iron Coffin

Mary Alexander

You're Not Welcome Here

Mississipppi Goddamn

Frankie and Johnny were lovers ......

The Killing of Eugene Williams

The Benjamin's Last Family Portrait

Thomas P Kelly vs. Josephine Kelly

Great American Foot Race: The Bunion Derby

Enterprising Women

Maria P Williams

Little Cake Walkers

Florence Mills

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

52 visits

Get Out! Reverse Freedom Rides

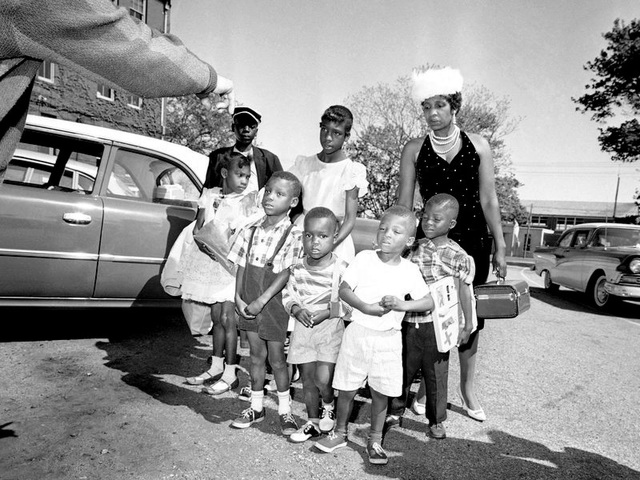

Lela Mae Williams and seven of her nine children on arrival in Hyannis. [Frank C. Curtin / Assoc. Press].

After three days on a Greyhound bus, Lela Mae Williams was just an hour from her destination—Hyannis, Massachusetts—when she asked the bus driver to pull over. She needed to change into her finest clothes. She had been promised the Kennedy family would be waiting for her.

It was late on a Wednesday afternoon, nearly 60 years ago, when that Greyhound bus from Little Rock, Arkansas, pulled into Hyannis. It slowed to a stop near the summer home of President John F. Kennedy and his family. When the doors opened, Lela Mae and her nine youngest children stepped onto the pavement.

"She was going to have a job, and she was going to be able to support her family," one of Lela Mae's daughters, Betty Williams, remembered in a recent interview. Before coming north to Massachusetts, Lela Mae had been promised a good job, good housing and a presidential welcome.

But President Kennedy was not there to meet her. And there was no job or permanent housing waiting for her in Hyannis. Instead, Lela Mae and the others were unwitting pawns in a segregationist game.

The Reverse Freedom Rides of 1962 were a deliberate parody of the Freedom Rides organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) the previous year. Also called the Freedom Rides North, African American "participants" in the Reverse Freedom Rides were offered free one-way transportation and the promise of free housing and guaranteed employment to Northern cities. George Singelmann of the Greater New Orleans Citizens' Council orchestrated the Reverse Freedom Rides, which served as the Citizens' Councils' means of testing the sincerity of Northern liberals' quest for equality for African Americans. This attempt to embarrass Northern critics of the Citizens' Councils was a way of, in Singelmann's words,

"telling the North to put up or shut up."

Within a week, the first of more than a dozen black Louisiana residents began arriving in Redwood Falls, the tiny Minnesota farm town where Parsons grew up. Initiated and fueled by George Singelmann of the White Citizens Council in New Orleans, the so-called Reverse Freedom Rides were a segregationist publicity stunt that eventually purchased one-way bus and train tickets for 200 to 300 African-American people to cities like New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles.

Originally, the plan was to send impoverished black families to Washington, D.C. "because that is the seat of the government and if they wanted to have the Negroes, we would help them," Singelmann, who died in 1990, said in a 1973 interview, part of an Amistad Research Center collection on the topic assembled by author Garry Boulard.

The summer of 1962 was an unusual one on Cape Cod. Along with the influx of vacationers, nearly fifty African Americans from the South, arrived by bus on Main Street Hyannis with the promises of finding jobs, housing, a new life and a welcome from President John F. Kennedy.

"The many champions of the Negro race in the northern cities will certainly welcome you and help you get settled," a flier said about the bus rides.

In an attempt to embarrass then-President John F. Kennedy for what was seen as his support of the civil rights movement.

Instead of meeting Kennedy, however, they were met by a concerned citizens committee, who had learned of the efforts of southern segregationists to get black people out of their towns by giving them a bus ticket, $5 and the addresses of welfare departments and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in northern cities.

Still, many travelers seized the chance to leave a region plagued with high unemployment. The first family to leave New Orleans, Louis and Dorothy Boyd and their eight children, arrived the day before Easter in 1962, and still lives in New Jersey.

The Williams family from Arkansas stayed in the North, too. "It was the right thing to do. I thank my mother," said Gloria Williams, who lives in Boston now, within walking distance of her mother and siblings, but was a teenager when her family got off the bus in Hyannis. Her mother, Lela Mae Williams, then 36, brought her nine youngest children from the small town of Huttig, Ark. in May and then sent for her older children Gloria and Betty. All received bus fare from the Little Rock segregationist citizens council.

"I didn't know what they were doing," Williams said. "I was terribly young. But my mother decided she was going to make a better life for her children. And she did."

Distinguishable only by who purchased their tickets, these riders became part of the so-called Second Great Migration, which spanned from 1941 to 1970. During that time, 5 million black Southerners moved to cities in the Midwest, North and the West. A Brookings Institution analysis of U.S. Census data found that between 1965 and 1970, 4,886 black New Orleanians became part of the migration.

New Orleanian Junius Eli, who died in 2004, was 19 at the time and skipped his college classes to take the 44-hour bus ride to New York as a lark of sorts, said his sister Ernestine Bradley. So when her brother phoned home, he met with disapproval. "My mother said something like, 'Boy, you better get yourself back home,'" Bradley said.

Eli arrived on a bus with six other men in May 1962, in the early days of the rides.

Eli and others found jobs and were housed at the Harlem YMCA. But 10 days later, Eli followed his mother's advice, thanks to a $44 train ticket paid for by North Carolina columnist Harry Golden, a critic of the rides.

"When the families initially arrived, they had hope," said Arthur Dunphy, 76, a National Guard captain called to duty to run a compound on nearby Camp Edwards that took care of the travelers until they got on their feet. There, he said, they were housed in unused barracks with only Army blankets separating families and movies shown at night by soldiers who volunteered to run the projector.

The buildings have since been demolished but when Dunphy returns to the base, he sometimes walks by the concrete foundations of the barracks where the families lived. "It's like ghosts coming out of the walls, the stories of that time," he said.

"The families weren't looking for anything we didn't want: a better opportunity for yourself and your kids," Dunphy said. "The citizens councils treated them like pawns. But they were just nice people, looking for a better life."

Sources: Amistad Research Center (Andrew Salinas); wickedlocal.com (article by Susan Vaughn, Jan 2013); The Times-Picayune (article by Katy Reckdah, May 2011);

After three days on a Greyhound bus, Lela Mae Williams was just an hour from her destination—Hyannis, Massachusetts—when she asked the bus driver to pull over. She needed to change into her finest clothes. She had been promised the Kennedy family would be waiting for her.

It was late on a Wednesday afternoon, nearly 60 years ago, when that Greyhound bus from Little Rock, Arkansas, pulled into Hyannis. It slowed to a stop near the summer home of President John F. Kennedy and his family. When the doors opened, Lela Mae and her nine youngest children stepped onto the pavement.

"She was going to have a job, and she was going to be able to support her family," one of Lela Mae's daughters, Betty Williams, remembered in a recent interview. Before coming north to Massachusetts, Lela Mae had been promised a good job, good housing and a presidential welcome.

But President Kennedy was not there to meet her. And there was no job or permanent housing waiting for her in Hyannis. Instead, Lela Mae and the others were unwitting pawns in a segregationist game.

The Reverse Freedom Rides of 1962 were a deliberate parody of the Freedom Rides organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) the previous year. Also called the Freedom Rides North, African American "participants" in the Reverse Freedom Rides were offered free one-way transportation and the promise of free housing and guaranteed employment to Northern cities. George Singelmann of the Greater New Orleans Citizens' Council orchestrated the Reverse Freedom Rides, which served as the Citizens' Councils' means of testing the sincerity of Northern liberals' quest for equality for African Americans. This attempt to embarrass Northern critics of the Citizens' Councils was a way of, in Singelmann's words,

"telling the North to put up or shut up."

Within a week, the first of more than a dozen black Louisiana residents began arriving in Redwood Falls, the tiny Minnesota farm town where Parsons grew up. Initiated and fueled by George Singelmann of the White Citizens Council in New Orleans, the so-called Reverse Freedom Rides were a segregationist publicity stunt that eventually purchased one-way bus and train tickets for 200 to 300 African-American people to cities like New York, Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles.

Originally, the plan was to send impoverished black families to Washington, D.C. "because that is the seat of the government and if they wanted to have the Negroes, we would help them," Singelmann, who died in 1990, said in a 1973 interview, part of an Amistad Research Center collection on the topic assembled by author Garry Boulard.

The summer of 1962 was an unusual one on Cape Cod. Along with the influx of vacationers, nearly fifty African Americans from the South, arrived by bus on Main Street Hyannis with the promises of finding jobs, housing, a new life and a welcome from President John F. Kennedy.

"The many champions of the Negro race in the northern cities will certainly welcome you and help you get settled," a flier said about the bus rides.

In an attempt to embarrass then-President John F. Kennedy for what was seen as his support of the civil rights movement.

Instead of meeting Kennedy, however, they were met by a concerned citizens committee, who had learned of the efforts of southern segregationists to get black people out of their towns by giving them a bus ticket, $5 and the addresses of welfare departments and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in northern cities.

Still, many travelers seized the chance to leave a region plagued with high unemployment. The first family to leave New Orleans, Louis and Dorothy Boyd and their eight children, arrived the day before Easter in 1962, and still lives in New Jersey.

The Williams family from Arkansas stayed in the North, too. "It was the right thing to do. I thank my mother," said Gloria Williams, who lives in Boston now, within walking distance of her mother and siblings, but was a teenager when her family got off the bus in Hyannis. Her mother, Lela Mae Williams, then 36, brought her nine youngest children from the small town of Huttig, Ark. in May and then sent for her older children Gloria and Betty. All received bus fare from the Little Rock segregationist citizens council.

"I didn't know what they were doing," Williams said. "I was terribly young. But my mother decided she was going to make a better life for her children. And she did."

Distinguishable only by who purchased their tickets, these riders became part of the so-called Second Great Migration, which spanned from 1941 to 1970. During that time, 5 million black Southerners moved to cities in the Midwest, North and the West. A Brookings Institution analysis of U.S. Census data found that between 1965 and 1970, 4,886 black New Orleanians became part of the migration.

New Orleanian Junius Eli, who died in 2004, was 19 at the time and skipped his college classes to take the 44-hour bus ride to New York as a lark of sorts, said his sister Ernestine Bradley. So when her brother phoned home, he met with disapproval. "My mother said something like, 'Boy, you better get yourself back home,'" Bradley said.

Eli arrived on a bus with six other men in May 1962, in the early days of the rides.

Eli and others found jobs and were housed at the Harlem YMCA. But 10 days later, Eli followed his mother's advice, thanks to a $44 train ticket paid for by North Carolina columnist Harry Golden, a critic of the rides.

"When the families initially arrived, they had hope," said Arthur Dunphy, 76, a National Guard captain called to duty to run a compound on nearby Camp Edwards that took care of the travelers until they got on their feet. There, he said, they were housed in unused barracks with only Army blankets separating families and movies shown at night by soldiers who volunteered to run the projector.

The buildings have since been demolished but when Dunphy returns to the base, he sometimes walks by the concrete foundations of the barracks where the families lived. "It's like ghosts coming out of the walls, the stories of that time," he said.

"The families weren't looking for anything we didn't want: a better opportunity for yourself and your kids," Dunphy said. "The citizens councils treated them like pawns. But they were just nice people, looking for a better life."

Sources: Amistad Research Center (Andrew Salinas); wickedlocal.com (article by Susan Vaughn, Jan 2013); The Times-Picayune (article by Katy Reckdah, May 2011);

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter