Frankie and Johnny were lovers ......

Mississipppi Goddamn

You're Not Welcome Here

Mary Alexander

Martha Peterson: Woman in the Iron Coffin

Wrightsville Survivors

Call and Post Newsboys

Hannah Elias: The Black Enchantress Who Was At One…

Mrs. A. J. Goode

Charles Collins: His 1902 Murder Became a Hallmar…

Searching for Eugene Williams

Nacirema Club Members

The Baker Family

A Harlem Street

Get Out! Reverse Freedom Rides

Savage Sideshow: Exhibiting Africans as Freaks

Lizzie Shephard

Under Siege

The Port Chicago Explosion and Mutiny

Stevedore --- New Orleans 1885

Pla-Mor Roller Skating Rink

Harlem's Dunbar Bank

Berry & Ross Doll Company

The Benjamin's Last Family Portrait

Thomas P Kelly vs. Josephine Kelly

Great American Foot Race: The Bunion Derby

Enterprising Women

Maria P Williams

Little Cake Walkers

Florence Mills

Emma Louise Hyers

Florence Mills: Harlem Jazz Queen

Belle Davis

First African American to perform at the White Hou…

Adelaide Hall

John W. Isham's The Octoroons

Birdie Gilmore

Charles S Gilpin

Inventor of Tap: William Henry Juba

Mamie Flowers: The Bronze Melba

Judy Pace

The First Black Child Movie Star

Angelina Weld Grimké

Sheila Guyse

Diana Sands

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

66 visits

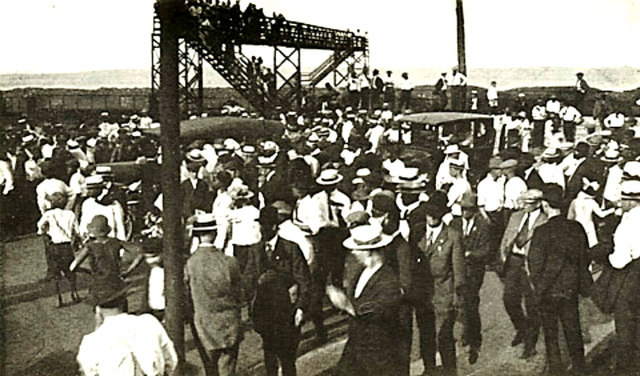

The Killing of Eugene Williams

The photograph depicts a white mob leaving Chicago's 29th Street Beach. The site of the stoning and subsequent drowning of 17 yr old Eugene Williams. The incident touched off the Chicago Race Riot.

1919 Chicago Race Riot, On the afternoon of July 27, 1919, Eugene Williams, a black youth, drowned off the 29th Street Beach. A stone throwing melee between blacks and whites on the beach prevented the boy from coming ashore safely. After clinging to a railroad tie for a lengthy period, he drowned when he no longer had the strength to hold on. This was the finding of the Cook County Coroner's Office after an inquest was held into the cause of his death.

William Tuttle, Jr.'s book, Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919, includes a 1969 interview with an eyewitness. This witness was one of the boys swimming and playing with Eugene Williams in Lake Michigan between 26th Street and the 29th Street Beach. He recalled having rocks thrown at them by a single white male standing on a breakwater 75 feet from their raft. Eugene was struck in the forehead and as his friend attempted to aid him, Eugene panicked and drowned.

The man on the breakwater left, running toward the 29th Street Beach. By this time rioting had already erupted there precipitated by vocal and physical demonstrations against a group of blacks who wanted to use the beach in defiance of its tacit designation as a "white" beach. The rioting escalated when a white police officer refused to arrest the white man, by now identified as the perpetrator of the separate incident near 26th Street. Instead he arrested a black individual. Anger over this, coupled with rumors and innuendos that spread in both camps regarding Eugene Williams' death led to 5 days of rioting in Chicago that ultimately claimed the lives of 23 blacks and 15 whites, with 291 wounded. The Coroner's Office spent 70 day sessions and 20 night sessions on inquest work and in examining 450 witnesses. Those findings, reported in the Coroner's Report of 1919 are followed by his recommendations to deal with the festering social and economic conditions that were the underlying factors of the riots. Anita Gonzalez & Ian Granick

Growing Racial Tensions, The "Red Summer" of 1919 marked the culmination of steadily growing tensions surrounding the great migration of African Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North that took place during World War I. When the war ended in late 1918, thousands of servicemen returned home from fighting in Europe to find that their jobs in factories, warehouses and mills had been filled by newly arrived Southern blacks or immigrants. Amid financial insecurity, racial and ethnic prejudices ran rampant. Meanwhile, African-American veterans who had risked their lives fighting for the causes of freedom and democracy found themselves denied basic rights such as adequate housing and equality under the law, leading them to become increasingly militant.

In this fraught atmosphere, the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan organization revived its violent activities in the South, including 64 lynchings in 1918 and 83 in 1919. In the summer of 1919, race riots would break out in Washington, D.C.; Knoxville, Tennessee; Longview, Texas; Phillips County, Arkansas; Omaha, Nebraska and--most dramatically--Chicago. The city's African-American population had increased from 44,000 in 1909 to more than 100,000 as of 1919. Competition for jobs in the city's stockyards was particularly intense, pitting African Americans against whites (both native-born and immigrants). Tensions ran highest on the city's South Side, where the great majority of black residents lived, many of them in old, dilapidated housing and without adequate services.

A Drowning in Lake Michigan, On July 27, 1919, a 17-year-old African American boy named Eugene Williams was swimming with friends in Lake Michigan when he crossed the unofficial barrier (located at 29th Street) between the city's "white" and "black" beaches. A group of white men threw stones at Williams, hitting him, and he drowned. When police officers arrived on the scene, they refused to arrest the white man whom black eyewitnesses pointed to as the responsible party. Angry crowds began to gather on the beach, and reports of the incident--many distorted or exaggerated spread quickly.

Violence soon broke out between gangs and mobs of black and white, concentrated in the South Side neighborhood surrounding the stockyards. After police were unable to quell the riots, the state militia was called in on the fourth day, but the fighting continued until August 3. Shootings, beatings and arson attacks eventually left 15 whites and 23 blacks dead, and more than 500 more people (around 60 percent black) injured. An additional 1,000 black families were left homeless after rioters torched their residences.

Lasting Impact, In the aftermath of the rioting, some suggested implementing zoning laws to formally segregate housing in Chicago, or restrictions preventing blacks from working alongside whites in the stockyards and other industries. Such measures were rejected by African-American and liberal white voters, however. City officials instead organized the Chicago Commission on Race Relations to look into the root causes of the riots and find ways to combat them. The commission, which included six white men and six black, suggested several key issues —including competition for jobs, inadequate housing options for blacks, inconsistent law enforcement and pervasive racial discrimination—but improvement in these areas would be slow in the years to come.

President Woodrow Wilson publicly blamed whites for being the instigators of race-related riots in both Chicago and Washington, D.C., and introduced efforts to foster racial harmony, including voluntary organizations and congressional legislation. In addition to drawing attention to the growing tensions in America's urban centers, the riots in Chicago and other cities in the summer of 1919 marked the beginning of a growing willingness among African Americans to fight for their rights in the face of oppression and injustice.

Sources: "Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919" by William Tuttle, Jr., Atheneum Press, NY, 1970], [history.com]

1919 Chicago Race Riot, On the afternoon of July 27, 1919, Eugene Williams, a black youth, drowned off the 29th Street Beach. A stone throwing melee between blacks and whites on the beach prevented the boy from coming ashore safely. After clinging to a railroad tie for a lengthy period, he drowned when he no longer had the strength to hold on. This was the finding of the Cook County Coroner's Office after an inquest was held into the cause of his death.

William Tuttle, Jr.'s book, Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919, includes a 1969 interview with an eyewitness. This witness was one of the boys swimming and playing with Eugene Williams in Lake Michigan between 26th Street and the 29th Street Beach. He recalled having rocks thrown at them by a single white male standing on a breakwater 75 feet from their raft. Eugene was struck in the forehead and as his friend attempted to aid him, Eugene panicked and drowned.

The man on the breakwater left, running toward the 29th Street Beach. By this time rioting had already erupted there precipitated by vocal and physical demonstrations against a group of blacks who wanted to use the beach in defiance of its tacit designation as a "white" beach. The rioting escalated when a white police officer refused to arrest the white man, by now identified as the perpetrator of the separate incident near 26th Street. Instead he arrested a black individual. Anger over this, coupled with rumors and innuendos that spread in both camps regarding Eugene Williams' death led to 5 days of rioting in Chicago that ultimately claimed the lives of 23 blacks and 15 whites, with 291 wounded. The Coroner's Office spent 70 day sessions and 20 night sessions on inquest work and in examining 450 witnesses. Those findings, reported in the Coroner's Report of 1919 are followed by his recommendations to deal with the festering social and economic conditions that were the underlying factors of the riots. Anita Gonzalez & Ian Granick

Growing Racial Tensions, The "Red Summer" of 1919 marked the culmination of steadily growing tensions surrounding the great migration of African Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North that took place during World War I. When the war ended in late 1918, thousands of servicemen returned home from fighting in Europe to find that their jobs in factories, warehouses and mills had been filled by newly arrived Southern blacks or immigrants. Amid financial insecurity, racial and ethnic prejudices ran rampant. Meanwhile, African-American veterans who had risked their lives fighting for the causes of freedom and democracy found themselves denied basic rights such as adequate housing and equality under the law, leading them to become increasingly militant.

In this fraught atmosphere, the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan organization revived its violent activities in the South, including 64 lynchings in 1918 and 83 in 1919. In the summer of 1919, race riots would break out in Washington, D.C.; Knoxville, Tennessee; Longview, Texas; Phillips County, Arkansas; Omaha, Nebraska and--most dramatically--Chicago. The city's African-American population had increased from 44,000 in 1909 to more than 100,000 as of 1919. Competition for jobs in the city's stockyards was particularly intense, pitting African Americans against whites (both native-born and immigrants). Tensions ran highest on the city's South Side, where the great majority of black residents lived, many of them in old, dilapidated housing and without adequate services.

A Drowning in Lake Michigan, On July 27, 1919, a 17-year-old African American boy named Eugene Williams was swimming with friends in Lake Michigan when he crossed the unofficial barrier (located at 29th Street) between the city's "white" and "black" beaches. A group of white men threw stones at Williams, hitting him, and he drowned. When police officers arrived on the scene, they refused to arrest the white man whom black eyewitnesses pointed to as the responsible party. Angry crowds began to gather on the beach, and reports of the incident--many distorted or exaggerated spread quickly.

Violence soon broke out between gangs and mobs of black and white, concentrated in the South Side neighborhood surrounding the stockyards. After police were unable to quell the riots, the state militia was called in on the fourth day, but the fighting continued until August 3. Shootings, beatings and arson attacks eventually left 15 whites and 23 blacks dead, and more than 500 more people (around 60 percent black) injured. An additional 1,000 black families were left homeless after rioters torched their residences.

Lasting Impact, In the aftermath of the rioting, some suggested implementing zoning laws to formally segregate housing in Chicago, or restrictions preventing blacks from working alongside whites in the stockyards and other industries. Such measures were rejected by African-American and liberal white voters, however. City officials instead organized the Chicago Commission on Race Relations to look into the root causes of the riots and find ways to combat them. The commission, which included six white men and six black, suggested several key issues —including competition for jobs, inadequate housing options for blacks, inconsistent law enforcement and pervasive racial discrimination—but improvement in these areas would be slow in the years to come.

President Woodrow Wilson publicly blamed whites for being the instigators of race-related riots in both Chicago and Washington, D.C., and introduced efforts to foster racial harmony, including voluntary organizations and congressional legislation. In addition to drawing attention to the growing tensions in America's urban centers, the riots in Chicago and other cities in the summer of 1919 marked the beginning of a growing willingness among African Americans to fight for their rights in the face of oppression and injustice.

Sources: "Race Riot: Chicago in the Red Summer of 1919" by William Tuttle, Jr., Atheneum Press, NY, 1970], [history.com]

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter