Great American Foot Race: The Bunion Derby

Thomas P Kelly vs. Josephine Kelly

The Benjamin's Last Family Portrait

The Killing of Eugene Williams

Frankie and Johnny were lovers ......

Mississipppi Goddamn

You're Not Welcome Here

Mary Alexander

Martha Peterson: Woman in the Iron Coffin

Wrightsville Survivors

Call and Post Newsboys

Hannah Elias: The Black Enchantress Who Was At One…

Mrs. A. J. Goode

Charles Collins: His 1902 Murder Became a Hallmar…

Searching for Eugene Williams

Nacirema Club Members

The Baker Family

A Harlem Street

Get Out! Reverse Freedom Rides

Savage Sideshow: Exhibiting Africans as Freaks

Lizzie Shephard

Under Siege

The Port Chicago Explosion and Mutiny

Maria P Williams

Little Cake Walkers

Florence Mills

Emma Louise Hyers

Florence Mills: Harlem Jazz Queen

Belle Davis

First African American to perform at the White Hou…

Adelaide Hall

John W. Isham's The Octoroons

Birdie Gilmore

Charles S Gilpin

Inventor of Tap: William Henry Juba

Mamie Flowers: The Bronze Melba

Judy Pace

The First Black Child Movie Star

Angelina Weld Grimké

Sheila Guyse

Diana Sands

Elizabeth Welch

Theodore Drury

The first 'Carmen Jones' Muriel Smith

Margot Webb

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

29 visits

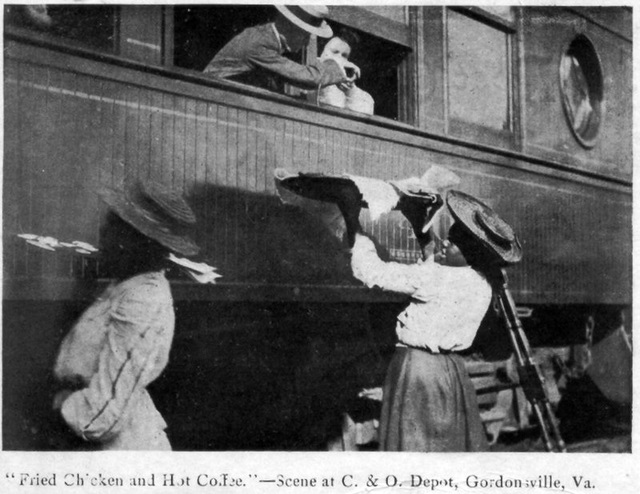

Enterprising Women

Waiter carriers pass food to passengers on a train stopping in Gordonsville, Virginia, in this undated photo. After the Civil War, local African American women found a route to financial freedom by selling their famous fried chicken and other home-made goods track-side. [Photo: Town of Gordonsville]

Fried chicken is a racially fraught food. Historically, it's been associated with racist depictions of African-Americans, and today, some still wield the fried-chicken-eating stereotype as an insult. But in some cases, the food itself has provided a path toward financial freedom for blacks.

Take the town of Gordonsville, Virginia, for example. As Lauren Ober of NPR member station WAMU recently reported, in the latter half of the 1800s, the town gained fame as the "Fried Chicken Capital of the World." And the reasons why date back to the rise of the railroad.

By the time the Civil War broke out, the town was a main stop on two rail lines. It was also a major transportation hub for produce coming from Virginia's Shenandoah Valley.

But those trains didn't have dining cars, and local African-American women found a business opportunity in hungry passengers. The women would cook up fried chicken, biscuits, pies and other tasty goods and sell them from the train platform, passing the food over to passengers through the open windows.

These vendors, known as waiter carriers because they had to transport the food a long way to get to the station, developed a reputation for their culinary skills, according to Psyche Williams-Forson, an associate professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland.

"Some people would deliberately chart their way through Gordonsville because they knew they would encounter these women and those particular foodstuffs," Williams-Forson tells Ober.

For the waiter carriers of Gordonsville, fried chicken became an avenue of economic empowerment after the Civil War. The title of Williams-Forson's 2006 book, "Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food and Power," is a nod to this entrepreneurial legacy: Bella Winston, an 80-year-old former waiter carrier, who learned the trade from her mother, told a local newspaper in 1970, "My mother paid for this place with chicken legs."

That degree of economic independence was rare for African-Americans post-emancipation, Gordonsville Mayor Bob Coiner tells Ober:

"At the end of the Civil War, when we have new freedoms for people, they're put in a position where they need jobs," says Coiner, whose family has lived in Gordonsville for many generations. "The situation was bad before, but you could count on the situation. Now it was a big unknown."

The waiter carriers were part of a larger tradition of African-American women who found economic independence — in some cases even buying their own freedom — through their cooking skills. Indeed, one of the first cookbooks published by a black woman in America was put out by an ex-slave woman in 1881.

Williams-Forson writes that the historical record is sparse when it comes to Gordonsville's fried chicken vendors. But, she tells Ober, "I think it's important to talk about it, because it reflects some level of agency that some African-Americans were able to exhibit during that horrible institution."

Of course, fried chicken is a particularly racially charged dish. To wit: the Coon Chicken Inn, a restaurant chain begun in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1925, that was popular for its fried chicken. The decor was as racist as the name. The caricature of a black man with grotesquely oversized red, open, smiling lips, a porter's hat askew on his head, was ubiquitous: on silverware, menus, matchbooks and other advertising. Customers had to walk through a giant version of those grinning lips to enter the restaurants.

"Back in those days ... it wasn't nothing to see such mockery. Black folks was always being mocked," according to former headwaiter Roy Hawkins, whose recollections of working there appear in Williams-Forson's book.

As for the waiter carriers of Gordonsville, their trade disappeared in the first half of the 20th century, as dining cars were added to trains and government regulations cracked down on track-side food vendors. But their legacy lives on in Gordonsville, which hosts an annual fried chicken contest.

Gravy the Podcast (Fried Chicken a Complicated Comfort Food)

www.southernfoodways.org/gravy/fried-chicken-a-complicate...

Sources: Lauren Ober's report on Gordonsville's fried chicken tradition aired on member supported radio station WAMU in Washington, D.C. You can listen to a longer version of that story, which details other ways that African American women have found economic empowerment through food, from Gravy, the podcast from the Southern Foodways Alliance.

Fried chicken is a racially fraught food. Historically, it's been associated with racist depictions of African-Americans, and today, some still wield the fried-chicken-eating stereotype as an insult. But in some cases, the food itself has provided a path toward financial freedom for blacks.

Take the town of Gordonsville, Virginia, for example. As Lauren Ober of NPR member station WAMU recently reported, in the latter half of the 1800s, the town gained fame as the "Fried Chicken Capital of the World." And the reasons why date back to the rise of the railroad.

By the time the Civil War broke out, the town was a main stop on two rail lines. It was also a major transportation hub for produce coming from Virginia's Shenandoah Valley.

But those trains didn't have dining cars, and local African-American women found a business opportunity in hungry passengers. The women would cook up fried chicken, biscuits, pies and other tasty goods and sell them from the train platform, passing the food over to passengers through the open windows.

These vendors, known as waiter carriers because they had to transport the food a long way to get to the station, developed a reputation for their culinary skills, according to Psyche Williams-Forson, an associate professor of American Studies at the University of Maryland.

"Some people would deliberately chart their way through Gordonsville because they knew they would encounter these women and those particular foodstuffs," Williams-Forson tells Ober.

For the waiter carriers of Gordonsville, fried chicken became an avenue of economic empowerment after the Civil War. The title of Williams-Forson's 2006 book, "Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food and Power," is a nod to this entrepreneurial legacy: Bella Winston, an 80-year-old former waiter carrier, who learned the trade from her mother, told a local newspaper in 1970, "My mother paid for this place with chicken legs."

That degree of economic independence was rare for African-Americans post-emancipation, Gordonsville Mayor Bob Coiner tells Ober:

"At the end of the Civil War, when we have new freedoms for people, they're put in a position where they need jobs," says Coiner, whose family has lived in Gordonsville for many generations. "The situation was bad before, but you could count on the situation. Now it was a big unknown."

The waiter carriers were part of a larger tradition of African-American women who found economic independence — in some cases even buying their own freedom — through their cooking skills. Indeed, one of the first cookbooks published by a black woman in America was put out by an ex-slave woman in 1881.

Williams-Forson writes that the historical record is sparse when it comes to Gordonsville's fried chicken vendors. But, she tells Ober, "I think it's important to talk about it, because it reflects some level of agency that some African-Americans were able to exhibit during that horrible institution."

Of course, fried chicken is a particularly racially charged dish. To wit: the Coon Chicken Inn, a restaurant chain begun in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1925, that was popular for its fried chicken. The decor was as racist as the name. The caricature of a black man with grotesquely oversized red, open, smiling lips, a porter's hat askew on his head, was ubiquitous: on silverware, menus, matchbooks and other advertising. Customers had to walk through a giant version of those grinning lips to enter the restaurants.

"Back in those days ... it wasn't nothing to see such mockery. Black folks was always being mocked," according to former headwaiter Roy Hawkins, whose recollections of working there appear in Williams-Forson's book.

As for the waiter carriers of Gordonsville, their trade disappeared in the first half of the 20th century, as dining cars were added to trains and government regulations cracked down on track-side food vendors. But their legacy lives on in Gordonsville, which hosts an annual fried chicken contest.

Gravy the Podcast (Fried Chicken a Complicated Comfort Food)

www.southernfoodways.org/gravy/fried-chicken-a-complicate...

Sources: Lauren Ober's report on Gordonsville's fried chicken tradition aired on member supported radio station WAMU in Washington, D.C. You can listen to a longer version of that story, which details other ways that African American women have found economic empowerment through food, from Gravy, the podcast from the Southern Foodways Alliance.

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter