Josephine Braham Johnson

Lewis Hayden

Nancy Weston

Elisa Greenwell

Malvina 'Viney' Russell

"We Are Literally Slaves" An Early 20th Century B…

Mr. and Mrs. Henson

The Cazenovia Anti-Fugitive Slave Act Convention,…

From Slavery to Freedom to Prosperity

Picking Cotton on Alex Knox's Plantation

A Loving Daughter: Nellie Arnold Plummer

John Roy Lynch

Alvin Coffey

Enslaved No More: Wallace Turnage

Pedro Tovookan Parris

The 1st by 17 Years: The Story of Harry S. Murphy,…

Segregated to the Anteroom

Standing Tall Amid the Glares

We Finish to Begin

Give Me An 'A'!

Bertha Josephine Blue

McIntire's Childrens Home Baseball Team

Edith Irby Jones

Behind Union Lines

Isabella Gibbons

William 'Billy' Walker

Addison White

Ezekiel Gillespie

Adam Francis Plummer

Randolph Miller

Emancipators

Thomas W Burton, MD

Cudjoe Kossula Lewis: "The Last African-American A…

Caroline's Escape

David Ware

Wanderers No More

James Collins Johnson: Princeton's Property No Mor…

Howard Henriques Smith

Hero of Richmond Theater Disaster

The Story of James Henry Brooks

Ann Bicknell Ellis

Nelson Gant

John H Nichols

Wiley Hinds

Samuel Harper and Jane Hamilton

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

28 visits

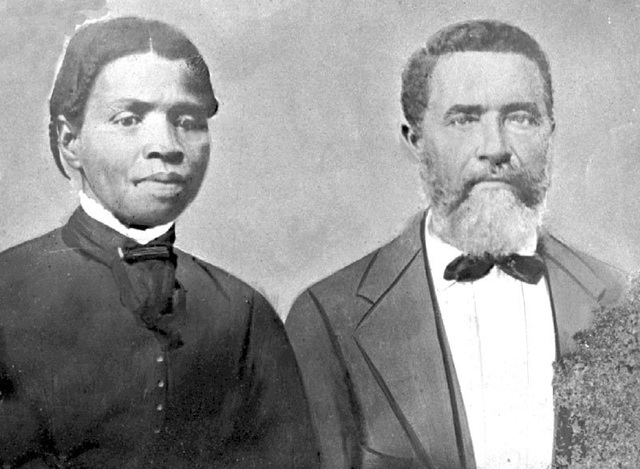

Mr. and Mrs. Hancock

Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock were among the first generation of newly freed to purchase and farm their own land in Travis County after the Civil War. Photograph, likely taken sometime between 1889 and 1899.

In an area now overrun by the busy interchange of Loop 1 and Parmer Lane in north Austin lie the remnants of what was once a thriving community of former African American slaves. Prominent in that community were Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock who, after emancipation, bought land, established a farm, and raised a family. Their story and that of their descendants and neighbors has been brought to life through archeological and historical investigations.

Rubin Hancock, his wife, Elizabeth, and many of their family members, were enslaved by a prominent Austin judge, John Hancock. Little is known about their early life, other than that they were all born into slavery. Rubin in Alabama and Elizabeth in Tennessee during the 1840s. Although Texas did not recognize slave marriages (which otherwise would have resulted in written records), it is known that the two were married, or committed as life partners, before they gained their freedom. More is known about the life and philosophies of the judge. Despite his reliance on slavery, Judge Hancock was adamantly opposed to Texas' secession from the Union. After being elected to the state legislature in 1860 as a Unionist, he was removed from office when he refused to swear allegiance to the Confederacy.

The 1860 Census entry for Judge Hancock notes his ownership of 15 slaves. Although none were individually listed, it is likely that Rubin Hancock and his brothers Orange, Salem, and Peyton were among them at that time. It is also likely, according to family histories, that the four men were half-brothers of the judge. Their considerable duties would have included clearing land, planting, and working a 300-acre dairy farm; maintaining cattle and other livestock on the judge's extensive ranch lands; and building a variety of structures.

The end of the Civil War in 1865 brought emancipation for slaves, announced in Texas on June 19, 1865. Sometime after that, Rubin and his three brothers bought land in the area north of Austin, making them landowners at a time when many others—Whites and African-Americans alike—were sharecroppers and tenants. With few resources available beyond their own strength and determination and the possible assistance of Rubin's former master, the judge—Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock established a productive farm, raised a family of five children, and helped establish a small but stable community of African-American farmers.

Known as Duval, the community was bound by family ties and a strong church, St. Stephen's Missionary Baptist, in which social gatherings, school classes for African-American children, and worship services were held. The coming of the A&NW railroad through the Hancock farm in 1881 meant an influx of families into the area and the new recreational resort of Summers Grove (later Waters Park). It also provided a means of transport for farm products, such as cotton from Rubin Hancock's fields, to nearby markets.

As was the case for many farm families of the time, life was difficult, with seemingly unending chores for adults and children alike. There was no running water or electricity; water was hauled from a well, and all cooking was done on a cast iron wood stove, for which wood had to be chopped each day. Kerosene lanterns provided lighting for the small house. The family raised cows and pigs, grew cotton and corn, and maintained a large vegetable garden and fruit trees. Surplus was sold to local store owners or sold in Austin.

According to family stories, the children found entertainment by playing baseball, marbles, and dominoes using handmade pieces made of cardboard. On Sundays, they attended Sunday school and church picnics at St. Paul's Baptist Church. Evenings often were filled with singing and socials with neighboring friends and relatives.

Elizabeth Hancock died in 1899. Rubin Hancock lived and continued to work the farm until well into his sixties, leaving finally to live with his daughter, Susie, until his death in 1916. The three surviving children, all daughters, kept the farm until 1942, when the house was moved off the site.

All of the Hancock brothers were able to own and work their own farms. Each registered to vote and each married and raised a family—members of which still prosper in the Austin area. All was created by the will and effort of a group of people who had just come out of the bonds of slavery. Freedom was sweet and they made the most of it.

Little remains today of the small communities that once dotted the landscape in north Austin, save for a few street signs bearing some of their names. Over the past 100 years, northwest Travis county has changed from a rural area to one of the fastest growing urban areas in the United States. When a highway extension was planned in the area of Duval Road and Loop 1, archeologists from the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) surveyed the area for evidence of significant cultural remains. They also examined old maps and records, and it was through these means that they learned of the Hancock farmstead. During the process, numerous descendants of the Hancock family, were contacted, and they attended the dedication ceremony for an historical marker at the site.

Sources: University of Texas at Austin; Photo courtesy of Lillian Robinson

In an area now overrun by the busy interchange of Loop 1 and Parmer Lane in north Austin lie the remnants of what was once a thriving community of former African American slaves. Prominent in that community were Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock who, after emancipation, bought land, established a farm, and raised a family. Their story and that of their descendants and neighbors has been brought to life through archeological and historical investigations.

Rubin Hancock, his wife, Elizabeth, and many of their family members, were enslaved by a prominent Austin judge, John Hancock. Little is known about their early life, other than that they were all born into slavery. Rubin in Alabama and Elizabeth in Tennessee during the 1840s. Although Texas did not recognize slave marriages (which otherwise would have resulted in written records), it is known that the two were married, or committed as life partners, before they gained their freedom. More is known about the life and philosophies of the judge. Despite his reliance on slavery, Judge Hancock was adamantly opposed to Texas' secession from the Union. After being elected to the state legislature in 1860 as a Unionist, he was removed from office when he refused to swear allegiance to the Confederacy.

The 1860 Census entry for Judge Hancock notes his ownership of 15 slaves. Although none were individually listed, it is likely that Rubin Hancock and his brothers Orange, Salem, and Peyton were among them at that time. It is also likely, according to family histories, that the four men were half-brothers of the judge. Their considerable duties would have included clearing land, planting, and working a 300-acre dairy farm; maintaining cattle and other livestock on the judge's extensive ranch lands; and building a variety of structures.

The end of the Civil War in 1865 brought emancipation for slaves, announced in Texas on June 19, 1865. Sometime after that, Rubin and his three brothers bought land in the area north of Austin, making them landowners at a time when many others—Whites and African-Americans alike—were sharecroppers and tenants. With few resources available beyond their own strength and determination and the possible assistance of Rubin's former master, the judge—Rubin and Elizabeth Hancock established a productive farm, raised a family of five children, and helped establish a small but stable community of African-American farmers.

Known as Duval, the community was bound by family ties and a strong church, St. Stephen's Missionary Baptist, in which social gatherings, school classes for African-American children, and worship services were held. The coming of the A&NW railroad through the Hancock farm in 1881 meant an influx of families into the area and the new recreational resort of Summers Grove (later Waters Park). It also provided a means of transport for farm products, such as cotton from Rubin Hancock's fields, to nearby markets.

As was the case for many farm families of the time, life was difficult, with seemingly unending chores for adults and children alike. There was no running water or electricity; water was hauled from a well, and all cooking was done on a cast iron wood stove, for which wood had to be chopped each day. Kerosene lanterns provided lighting for the small house. The family raised cows and pigs, grew cotton and corn, and maintained a large vegetable garden and fruit trees. Surplus was sold to local store owners or sold in Austin.

According to family stories, the children found entertainment by playing baseball, marbles, and dominoes using handmade pieces made of cardboard. On Sundays, they attended Sunday school and church picnics at St. Paul's Baptist Church. Evenings often were filled with singing and socials with neighboring friends and relatives.

Elizabeth Hancock died in 1899. Rubin Hancock lived and continued to work the farm until well into his sixties, leaving finally to live with his daughter, Susie, until his death in 1916. The three surviving children, all daughters, kept the farm until 1942, when the house was moved off the site.

All of the Hancock brothers were able to own and work their own farms. Each registered to vote and each married and raised a family—members of which still prosper in the Austin area. All was created by the will and effort of a group of people who had just come out of the bonds of slavery. Freedom was sweet and they made the most of it.

Little remains today of the small communities that once dotted the landscape in north Austin, save for a few street signs bearing some of their names. Over the past 100 years, northwest Travis county has changed from a rural area to one of the fastest growing urban areas in the United States. When a highway extension was planned in the area of Duval Road and Loop 1, archeologists from the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT) surveyed the area for evidence of significant cultural remains. They also examined old maps and records, and it was through these means that they learned of the Hancock farmstead. During the process, numerous descendants of the Hancock family, were contacted, and they attended the dedication ceremony for an historical marker at the site.

Sources: University of Texas at Austin; Photo courtesy of Lillian Robinson

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter