Nelson Gant

Ann Bicknell Ellis

The Story of James Henry Brooks

Hero of Richmond Theater Disaster

Howard Henriques Smith

James Collins Johnson: Princeton's Property No Mor…

Wanderers No More

David Ware

Caroline's Escape

Cudjoe Kossula Lewis: "The Last African-American A…

Thomas W Burton, MD

Emancipators

Randolph Miller

Adam Francis Plummer

Ezekiel Gillespie

Addison White

William 'Billy' Walker

Isabella Gibbons

Behind Union Lines

Mr. and Mrs. Hancock

Josephine Braham Johnson

Lewis Hayden

Nancy Weston

Wiley Hinds

Samuel Harper and Jane Hamilton

Frederick Foote, Sr.

3X Great Grandson Remembers

The Gardners

Nancy Green

Caldonia Fackler 'Cal' Johnson

Please Hear Our Prayers

The Truth's Daughter

Edmondson Sisters

George W Lowther

The Woman Who Escaped Enslavement by President Geo…

No Longer Hidden

Ellen Craft

Ruth Cox Adams

Siah Hulett Carter: Escape on the Monitor

Letter from a Freed Man: Jourdan Anderson

John Dabney

George O. Brown

Sara Baro Colcher

Freedom with the Joneses

Jim Hercules

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

29 visits

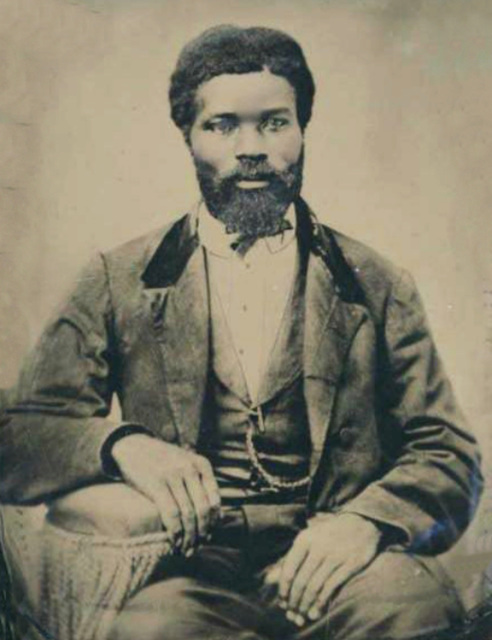

John H Nichols

Escape from Slavery Through

The Dismal Swamp — The Experience

of John Nichols, A Lewiston Citizen

By L. C. Bateman

Lewiston Journal Illustrated Magazine

(magazine article published April 16, 1921)

How many of our people know that a former North Carolina slave is now living in Lewiston as one of its highly respected citizens? This is John H. Nichols of Central Avenue. Mr. Nichols made a wonderful escape in the early months of 1862 and crossed the entire Dismal Swamp without chart or compass, reaching the lines of the Union armies when but fourteen years of age. Born and reared a slave, he had an instinctive love of freedom and when yet but a child made his way through the horrors of the famous swamp immortalized by the genius of Tom Moore and reached a freedom of which he had hardly dared to hope.

The great body of southern slaves were made free by the Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln and remained on the old plantation, but here was a young lad taking the most dangerous chances in a vast swamp of which he knew but little beyond the fact that it was as pathless as the sea, reeking with poisonous vipers and inhabited only by wild animals and venomous snakes. For nearly three days and nights he worked his way through the tangled underbrush, much of the time crawling on his hands and knees and listening to the hissing vipers that he disturbed. It is difficult at this distance of time to fully realize what this meant. No wonder that he values the liberty that he gained by such a desperate adventure.

But what are we to think of the causes that lead to such a condition of affairs? A so-called Christian nation dealing with human beings as with cattle and swine! And yet there are those around us today who believed and supported such an infamous system, and who are still obdurate in opposing every God given movement to benefit mankind! Thank God for such men as William Lloyrd Garrison and Wendell Phillips who dared to brave the storms of hatred in breaking down a system so vile and inhuman.

Mr. Nichols was born in Paspatance [Pasquotank] County, North Carolina, at the foot of the Dismal Swamp. His parents were slaves but his mother had died while he was yet a child, while the father had been sold to another man who owned a plantation but a short distance away, and this was but another infamous feature of the system of slavery. Parents were separated from their children and from each other and sent where they could never again meetin fraternal and parental clasp. It was a terrible system and one upon which the curse of God was bound to descend.

It was a short time since that the writer visited Mr. Nichols in his home and heard, from his own lips, of his early life as a slave, a story that no romance could surpass.

“The name of my master was Dempsey Richardson, and as a slave I took his name while I was on his plantation. That was the custom among the slaves. I had formerly been the property of his father, Ivory Richardson, but when he died all the slaves went to the son with the other property. I can remember back to a few years before the war, but when father was sold I began to realize that slavery was the greatest curse on God’s earth. And yet my case was not one of the hardest by any means as my master was really a kind man.

“Father was on a plantation but a mile or two away and I could see him now and then on Sunday or during the evening. Mother was dead and all the relatives I had were two uncles who were owned several miles away.

“I want to do my master full justice and I will say that he was reasonably kind to his slaves of whom he owned about thirty in all. The slave owners were much like the cattle owners here. Some were kind and others were cruel. The man who took care of his slaves got the most work out of them. You know there are men here who lick their cattle and horses but the horses do not do as much work and the cows do not give as much milk when they are beaten.

“We did not raise cotton on our plantation. It was wheat, corn, and potatoes. I was too young to do the hardest work but was compelled to learn all kinds of work on the plantation. I was an active and willing boy and for that reason got but few whippings.

“I was never whipped but once severely, and I have still got a scar on my side where the lash fell. The boss of the farm did it and used a hickory stick. They also used rawhide whips and these were even worse when laid on the bare flesh.

“The slaves all lived in little cabins of two rooms each and were huddled closely together. We were compelled to work from sun to sun but had our evenings for amusement when not too tired. I used to hire out now and then to work evenings and got a little money in that way. Some of the older ones earned enough money in this way to buy their freedom when they grew older but these cases were rare. The average price of a slave was nearly $1,000, but this depended upon his strength and ability to work.

“It was said that I was worth $600, as I was young. My master was offered that amount for me but refused to sell as I was a promising boy. It was something terrible to be always expecting to be sold and go farther South.

“In those days a slave had no way to learn what was going on as they could neither read nor write and only knew what was told them. About 1862 we found out that a war was going on between the North and the South but we did not know what I meant. We were told by the whites that the Yankees were coming to take us to Cuba to work on sugar plantations but we did not want to go there. Some of the white men did not believe this but they did not dare to tell us. A few of these whites did not believe in slavery but they had to keep still if they valued their lives.

“After a time the war was known to everyone, but my master said they would whip the Yankees in a very few weeks. Six months was the very longest it would take to do this. Of course we didn’t know but that he was telling us the truth.”

As it came to be understood that Northern armies were on the other side of the Dismal Swamp it was whispered around among the slaves that there was a chance to escape. The father of young Nichols was one of the men who planned the scheme to cross the big swamp. Of course all the plantations for miles around had . . . slaves. Says Mr. Nichols:

“I lived in a cabin just back of my master’s home and there were twelve or fifteen of these cabins in all. Father lived only a short distance away and he made it his way to see all the slaves in that vicinity. All were so anxious to escape that they kept the secret very closely. News came to us now and then of the great armies less than 50 miles away and that only gave us courage to make the attempt.

“A colored man in the vicinity was familiar with the Dismal Swamp and he agreed to guide the party through for $300. This amount was raised among the Negroes who were in the scheme and paid over to the Negro guide. All kept quiet until all the plans were made and the time had come to make the attempt.

“It was a dark night, and we were assembled on the edge of the swamp. We were to start at midnight and follow a lumberman’s trail until the following morning. One by one the slaves silently left their cabins and by twelve o’clock nearly 300 men and women were ready for the plunge into the swamp but our guide was not there according to promise.

“A hurried council was held among the men and it was decided that the guide had played us false. As father had planned the whole scheme and knew something about the swamp he was chosen the leader and he at once advised making the start without the guide to whom the money had been paid. If the colored guide had merely played false but kept his mouth shut we would have made the escape a success but at the last moment he had told my master and the alarm was at once sounded. All the white men in the vicinity gathered and arming themselves started on our track.

“By the time the whites reached our starting point we had a start of several hours and were a long distance on our way. We were following an old canal that had been used to bring lumber out of the swamp and the first night was easy traveling. By morning the whites were up with us and then all was confusion. We were unarmed and the trail was growing worse. A parley was held and the slaves decided to return rather than be shot. A few of the boldest refused and plunged into the thicket. I was among them, and never did I run faster in my life.

“As the whites had captured the greatest number they had no relish to follow us into the deep forest. In all, there were seven of us, and these were soon separated and I found myself alone. It was a terrible experience for a boy my age. All trace of a road was lost and I was compelled to crawl on my hands and knees in order to get through the tangled jungle.

“It was 30 miles across the Dismal Swamp but I had a little hoe cake that I had brought with me and this kept up my strength. At night I laid down to sleep and so exhausted I was that I actually did sleep a little. I could hear the hissing of snakes and the scream of a panther and perhaps you can judge of my feelings. Moccasin snakes and vipers were around me and I could hear them although it was too dark to see them. I saw a few wild cats but these kept shy of me.

“Perhaps what terrified me more than all else was the fear of ghosts. The Negro slaves had been kept in ignorance and were very superstitious. They all believed in ghosts, good and bad, and I as a boy had been taught to believe in them. That first night in the darkness of that terrible swamp was something that I remember only with a shudder but cannot describe. In the morning I started on again as best I could.

“I always had a keen sense of location and a knowledge of the sun and stars. I knew that the settlement of Deep Creek [Virginia, at the northern end of the Dismal Swamp Canal ] was ahead of me and if I could make the so-called shingle bridge on the way the rest would be easy. This was a bridge over which shingles were taken across a stream by the lumberman. I had heard that Yankee soldiers were at Deep Creek and I had faith to believe that I could reach there before my strength failed.

“It was an awful journey and if I had to live it over again I doubt if the trip would be made. I knew, however, that if caught I would be sent to Georgia to wear my life away, as the song goes. My father’s name was Jim Hinton, that being the name of his master, and I knew that he must be somewhere near me and that only added to my agony. As a matter of fact I never heard from him again and supposed that he must have perished in the Dismal Swamp. He was one of the seven who broke away from the whites after being captured in the swamp.

“We were told that we would be taken to Georgia in great hay racks each drawn by four or six mules, and we made up our minds that we had rather die and it seemed like death to cross that Dismal Swamp. Father was a strongman and I was a child but God smiled on me! Our masters thought if they could get us to Georgia that we would be safe until after the Yankees were whipped.

“I have always felt more bitter against that colored traitor than against our masters. They were after us the same as you would go after your cattle if they broke out of the pasture, while this Negro guide was a slave himself, and yet didn’t want to see us escape after taking $300 to guide us to the foot of the shingle bridge. He promised faithfully to guide us to safety and then notified the whites when we started.

“Well, I fear that I may tire you with this story, as I am tiring myself. I had slept a little, but the next night got no sleep at all. I was sort of delirious. I was constantly expecting bloodhounds on my track but fortunately these did not come.

The whites seemed to have no hounds with them and probably thought that as they had captured most of their property it was not worthwhile following the few who fled into the jungle.

“I had got so accustomed to snakes that I had little fear of them. The moccasins were more dangerous than the rattlers but I was not attacked by any of them. The rattler never chases a person and only strikes when you come near to him when coiled up. I would like to see all the snakes in the Dismal Swamp gathered in one spot big enough to hold them. It would be a wonderful sight, but I saw enough on that journey to last me through my life.

“To make a long story short, much of my trip was traced by the old canal, and I knew that would bring me out somewhere in time. After nearly three days in the wilderness I came out near a settlement called Portsmouth [just across the state line in Virginia], and there found some Union pickets on guard.

“One by one the other slaves came straggling in until there were six of us who had started on that fearful journey. The soldiers told us to go into the woods and build a fire and they would give us something to cook. After that we must report to the Provost Marshall. This we did and he gave us a permit to go on a boat to Harrison Landing. There we entered government service driving mules and doing other service work like handling ammunition.

“That gave us two great advantages. It first gave us security from our former masters and it also gave us plenty to eat and better than we ever had in our old slave cabins. I remained in the service until the closeof the war working between Portsmouth, Virginia, and Deep Creek, North Carolina. We were virtually right on the line of the two states and at times went as far as Culpepper Courthouse.

“I told you that I thought father died in the swamp but there is some doubt about that. One of my uncles afterwards told me that father was in Norfolk and wanted to have come come to him, but I refused as I felt safer with the army.

“I came to Maine at the close of the war with a party of colored men brought by Dr. [Alonzo] Garcelon [who had been an army surgeon]. He was in Lewiston [Maine] at the time and was anxious to get a colored man and woman to work on his farm. Some of his friends also wanted to get colored men. These were Dr. Kilbourne and Dr. Oakes of Auburn, Dr. Martin and Dr. Bradford of Lewiston and Dr. Garcelon undertook to bring on several ex-slaves from the South.

“This he did as he had the power to get them a free pass North. Garcelon was very kind to us when we reached Lewiston. He picked Bill Davis and his wife himself while I went to Colonel Ham and later to Dr. Martin. It was a good thing for us all to come to Lewiston, although I should like to go back to the old plantation once more before I die. I have an idea that I should see some of my old slave friends and it would be a wonderful meeting.

“Yes! I should like to visit my old home once more. My master is now dead but no doubt other members of the family are still living and I should have a pride in showing myself to them as a man and not as a slave. I do not know how they now feel about the system of slavery but I have no hard feelings towards them. They were brought up and educated to the system as something sacred and were sincere in their belief and willing to defend it with their blood. I would like to see the old plantation where I worked as a child, and would even like to go once more in the Dismal Swamp.

“Here are two hickory canes from the very road that we started in when escaping. Ex-Mayor [of Lewiston) Frank Morey owns a farm near the spot and when he was last down there he went into the swamp and cut these canes for me. He brought them back home and presented them to me in person. You cannot realize how much I value them or how grateful I feel to Mr. Morey. There are but few men who would have been thoughtful enough to do such a thing. To me they are dearer than the finest ebony gold headed cane. Mr. Morey owns a fine plantation there and has been on the same place where I lived as a slave. His place is nearer to Norfolk than where I lived.”

Mr. Nichols married Miss Marguerite Brooks of St. Andrews, New Brunswick, and to the couple thirteen children have been born. Of these but three are now living. Some of these died in early childhood and never realized the hardships of their father in slavery. There are six grandchildren and one of these, Elmer Russell, has been brought up by his grandparents. He is now eleven years of age, a student in the Lewiston schools and a very bright boy.

For many years Mr. Nichols has earned a living doing housecleaning and other odd jobs for people, and has won the good opinion and friendship of all he has served. He is a man of strong religious feeling and a constant attendant of the United Baptist Church where he and his family are highly regarded members.

In speaking to the Journal he said: “I thank God that my children were all born in freedom. Of all the horrors of slavery the selling of children from their parents was the worst. My usage as a slave was heaven [compared] to what some others endured. I have witnessed scenes so pathetic that they would move the heart of a stone. And yet when a child was torn away from its mother she never dared to show her grief. Do you wonder that I love the North with its glorious air of freedom? I can never be too thankful that I was brought to Lewiston by Dr. Garcelon. He was a noble man and I revere his memory.”

And who could believe that but a half century ago there were men here in Maine who would have consigned John H. Nichols to perpetual slavery? Truly, truth is stranger than fiction!

Sources: Abbe Museum; Maine Historical Society; Maine Maritime Museum; Northeast Harbor Maritime Museum; Northeast Harbor Library; Penobscot Marine Museum; Maine Granite Industry Historical Society Museum; Escape through the Dismal Swamp (Oct. 2019) davidcecelski.com

The Dismal Swamp — The Experience

of John Nichols, A Lewiston Citizen

By L. C. Bateman

Lewiston Journal Illustrated Magazine

(magazine article published April 16, 1921)

How many of our people know that a former North Carolina slave is now living in Lewiston as one of its highly respected citizens? This is John H. Nichols of Central Avenue. Mr. Nichols made a wonderful escape in the early months of 1862 and crossed the entire Dismal Swamp without chart or compass, reaching the lines of the Union armies when but fourteen years of age. Born and reared a slave, he had an instinctive love of freedom and when yet but a child made his way through the horrors of the famous swamp immortalized by the genius of Tom Moore and reached a freedom of which he had hardly dared to hope.

The great body of southern slaves were made free by the Emancipation Proclamation of Abraham Lincoln and remained on the old plantation, but here was a young lad taking the most dangerous chances in a vast swamp of which he knew but little beyond the fact that it was as pathless as the sea, reeking with poisonous vipers and inhabited only by wild animals and venomous snakes. For nearly three days and nights he worked his way through the tangled underbrush, much of the time crawling on his hands and knees and listening to the hissing vipers that he disturbed. It is difficult at this distance of time to fully realize what this meant. No wonder that he values the liberty that he gained by such a desperate adventure.

But what are we to think of the causes that lead to such a condition of affairs? A so-called Christian nation dealing with human beings as with cattle and swine! And yet there are those around us today who believed and supported such an infamous system, and who are still obdurate in opposing every God given movement to benefit mankind! Thank God for such men as William Lloyrd Garrison and Wendell Phillips who dared to brave the storms of hatred in breaking down a system so vile and inhuman.

Mr. Nichols was born in Paspatance [Pasquotank] County, North Carolina, at the foot of the Dismal Swamp. His parents were slaves but his mother had died while he was yet a child, while the father had been sold to another man who owned a plantation but a short distance away, and this was but another infamous feature of the system of slavery. Parents were separated from their children and from each other and sent where they could never again meetin fraternal and parental clasp. It was a terrible system and one upon which the curse of God was bound to descend.

It was a short time since that the writer visited Mr. Nichols in his home and heard, from his own lips, of his early life as a slave, a story that no romance could surpass.

“The name of my master was Dempsey Richardson, and as a slave I took his name while I was on his plantation. That was the custom among the slaves. I had formerly been the property of his father, Ivory Richardson, but when he died all the slaves went to the son with the other property. I can remember back to a few years before the war, but when father was sold I began to realize that slavery was the greatest curse on God’s earth. And yet my case was not one of the hardest by any means as my master was really a kind man.

“Father was on a plantation but a mile or two away and I could see him now and then on Sunday or during the evening. Mother was dead and all the relatives I had were two uncles who were owned several miles away.

“I want to do my master full justice and I will say that he was reasonably kind to his slaves of whom he owned about thirty in all. The slave owners were much like the cattle owners here. Some were kind and others were cruel. The man who took care of his slaves got the most work out of them. You know there are men here who lick their cattle and horses but the horses do not do as much work and the cows do not give as much milk when they are beaten.

“We did not raise cotton on our plantation. It was wheat, corn, and potatoes. I was too young to do the hardest work but was compelled to learn all kinds of work on the plantation. I was an active and willing boy and for that reason got but few whippings.

“I was never whipped but once severely, and I have still got a scar on my side where the lash fell. The boss of the farm did it and used a hickory stick. They also used rawhide whips and these were even worse when laid on the bare flesh.

“The slaves all lived in little cabins of two rooms each and were huddled closely together. We were compelled to work from sun to sun but had our evenings for amusement when not too tired. I used to hire out now and then to work evenings and got a little money in that way. Some of the older ones earned enough money in this way to buy their freedom when they grew older but these cases were rare. The average price of a slave was nearly $1,000, but this depended upon his strength and ability to work.

“It was said that I was worth $600, as I was young. My master was offered that amount for me but refused to sell as I was a promising boy. It was something terrible to be always expecting to be sold and go farther South.

“In those days a slave had no way to learn what was going on as they could neither read nor write and only knew what was told them. About 1862 we found out that a war was going on between the North and the South but we did not know what I meant. We were told by the whites that the Yankees were coming to take us to Cuba to work on sugar plantations but we did not want to go there. Some of the white men did not believe this but they did not dare to tell us. A few of these whites did not believe in slavery but they had to keep still if they valued their lives.

“After a time the war was known to everyone, but my master said they would whip the Yankees in a very few weeks. Six months was the very longest it would take to do this. Of course we didn’t know but that he was telling us the truth.”

As it came to be understood that Northern armies were on the other side of the Dismal Swamp it was whispered around among the slaves that there was a chance to escape. The father of young Nichols was one of the men who planned the scheme to cross the big swamp. Of course all the plantations for miles around had . . . slaves. Says Mr. Nichols:

“I lived in a cabin just back of my master’s home and there were twelve or fifteen of these cabins in all. Father lived only a short distance away and he made it his way to see all the slaves in that vicinity. All were so anxious to escape that they kept the secret very closely. News came to us now and then of the great armies less than 50 miles away and that only gave us courage to make the attempt.

“A colored man in the vicinity was familiar with the Dismal Swamp and he agreed to guide the party through for $300. This amount was raised among the Negroes who were in the scheme and paid over to the Negro guide. All kept quiet until all the plans were made and the time had come to make the attempt.

“It was a dark night, and we were assembled on the edge of the swamp. We were to start at midnight and follow a lumberman’s trail until the following morning. One by one the slaves silently left their cabins and by twelve o’clock nearly 300 men and women were ready for the plunge into the swamp but our guide was not there according to promise.

“A hurried council was held among the men and it was decided that the guide had played us false. As father had planned the whole scheme and knew something about the swamp he was chosen the leader and he at once advised making the start without the guide to whom the money had been paid. If the colored guide had merely played false but kept his mouth shut we would have made the escape a success but at the last moment he had told my master and the alarm was at once sounded. All the white men in the vicinity gathered and arming themselves started on our track.

“By the time the whites reached our starting point we had a start of several hours and were a long distance on our way. We were following an old canal that had been used to bring lumber out of the swamp and the first night was easy traveling. By morning the whites were up with us and then all was confusion. We were unarmed and the trail was growing worse. A parley was held and the slaves decided to return rather than be shot. A few of the boldest refused and plunged into the thicket. I was among them, and never did I run faster in my life.

“As the whites had captured the greatest number they had no relish to follow us into the deep forest. In all, there were seven of us, and these were soon separated and I found myself alone. It was a terrible experience for a boy my age. All trace of a road was lost and I was compelled to crawl on my hands and knees in order to get through the tangled jungle.

“It was 30 miles across the Dismal Swamp but I had a little hoe cake that I had brought with me and this kept up my strength. At night I laid down to sleep and so exhausted I was that I actually did sleep a little. I could hear the hissing of snakes and the scream of a panther and perhaps you can judge of my feelings. Moccasin snakes and vipers were around me and I could hear them although it was too dark to see them. I saw a few wild cats but these kept shy of me.

“Perhaps what terrified me more than all else was the fear of ghosts. The Negro slaves had been kept in ignorance and were very superstitious. They all believed in ghosts, good and bad, and I as a boy had been taught to believe in them. That first night in the darkness of that terrible swamp was something that I remember only with a shudder but cannot describe. In the morning I started on again as best I could.

“I always had a keen sense of location and a knowledge of the sun and stars. I knew that the settlement of Deep Creek [Virginia, at the northern end of the Dismal Swamp Canal ] was ahead of me and if I could make the so-called shingle bridge on the way the rest would be easy. This was a bridge over which shingles were taken across a stream by the lumberman. I had heard that Yankee soldiers were at Deep Creek and I had faith to believe that I could reach there before my strength failed.

“It was an awful journey and if I had to live it over again I doubt if the trip would be made. I knew, however, that if caught I would be sent to Georgia to wear my life away, as the song goes. My father’s name was Jim Hinton, that being the name of his master, and I knew that he must be somewhere near me and that only added to my agony. As a matter of fact I never heard from him again and supposed that he must have perished in the Dismal Swamp. He was one of the seven who broke away from the whites after being captured in the swamp.

“We were told that we would be taken to Georgia in great hay racks each drawn by four or six mules, and we made up our minds that we had rather die and it seemed like death to cross that Dismal Swamp. Father was a strongman and I was a child but God smiled on me! Our masters thought if they could get us to Georgia that we would be safe until after the Yankees were whipped.

“I have always felt more bitter against that colored traitor than against our masters. They were after us the same as you would go after your cattle if they broke out of the pasture, while this Negro guide was a slave himself, and yet didn’t want to see us escape after taking $300 to guide us to the foot of the shingle bridge. He promised faithfully to guide us to safety and then notified the whites when we started.

“Well, I fear that I may tire you with this story, as I am tiring myself. I had slept a little, but the next night got no sleep at all. I was sort of delirious. I was constantly expecting bloodhounds on my track but fortunately these did not come.

The whites seemed to have no hounds with them and probably thought that as they had captured most of their property it was not worthwhile following the few who fled into the jungle.

“I had got so accustomed to snakes that I had little fear of them. The moccasins were more dangerous than the rattlers but I was not attacked by any of them. The rattler never chases a person and only strikes when you come near to him when coiled up. I would like to see all the snakes in the Dismal Swamp gathered in one spot big enough to hold them. It would be a wonderful sight, but I saw enough on that journey to last me through my life.

“To make a long story short, much of my trip was traced by the old canal, and I knew that would bring me out somewhere in time. After nearly three days in the wilderness I came out near a settlement called Portsmouth [just across the state line in Virginia], and there found some Union pickets on guard.

“One by one the other slaves came straggling in until there were six of us who had started on that fearful journey. The soldiers told us to go into the woods and build a fire and they would give us something to cook. After that we must report to the Provost Marshall. This we did and he gave us a permit to go on a boat to Harrison Landing. There we entered government service driving mules and doing other service work like handling ammunition.

“That gave us two great advantages. It first gave us security from our former masters and it also gave us plenty to eat and better than we ever had in our old slave cabins. I remained in the service until the closeof the war working between Portsmouth, Virginia, and Deep Creek, North Carolina. We were virtually right on the line of the two states and at times went as far as Culpepper Courthouse.

“I told you that I thought father died in the swamp but there is some doubt about that. One of my uncles afterwards told me that father was in Norfolk and wanted to have come come to him, but I refused as I felt safer with the army.

“I came to Maine at the close of the war with a party of colored men brought by Dr. [Alonzo] Garcelon [who had been an army surgeon]. He was in Lewiston [Maine] at the time and was anxious to get a colored man and woman to work on his farm. Some of his friends also wanted to get colored men. These were Dr. Kilbourne and Dr. Oakes of Auburn, Dr. Martin and Dr. Bradford of Lewiston and Dr. Garcelon undertook to bring on several ex-slaves from the South.

“This he did as he had the power to get them a free pass North. Garcelon was very kind to us when we reached Lewiston. He picked Bill Davis and his wife himself while I went to Colonel Ham and later to Dr. Martin. It was a good thing for us all to come to Lewiston, although I should like to go back to the old plantation once more before I die. I have an idea that I should see some of my old slave friends and it would be a wonderful meeting.

“Yes! I should like to visit my old home once more. My master is now dead but no doubt other members of the family are still living and I should have a pride in showing myself to them as a man and not as a slave. I do not know how they now feel about the system of slavery but I have no hard feelings towards them. They were brought up and educated to the system as something sacred and were sincere in their belief and willing to defend it with their blood. I would like to see the old plantation where I worked as a child, and would even like to go once more in the Dismal Swamp.

“Here are two hickory canes from the very road that we started in when escaping. Ex-Mayor [of Lewiston) Frank Morey owns a farm near the spot and when he was last down there he went into the swamp and cut these canes for me. He brought them back home and presented them to me in person. You cannot realize how much I value them or how grateful I feel to Mr. Morey. There are but few men who would have been thoughtful enough to do such a thing. To me they are dearer than the finest ebony gold headed cane. Mr. Morey owns a fine plantation there and has been on the same place where I lived as a slave. His place is nearer to Norfolk than where I lived.”

Mr. Nichols married Miss Marguerite Brooks of St. Andrews, New Brunswick, and to the couple thirteen children have been born. Of these but three are now living. Some of these died in early childhood and never realized the hardships of their father in slavery. There are six grandchildren and one of these, Elmer Russell, has been brought up by his grandparents. He is now eleven years of age, a student in the Lewiston schools and a very bright boy.

For many years Mr. Nichols has earned a living doing housecleaning and other odd jobs for people, and has won the good opinion and friendship of all he has served. He is a man of strong religious feeling and a constant attendant of the United Baptist Church where he and his family are highly regarded members.

In speaking to the Journal he said: “I thank God that my children were all born in freedom. Of all the horrors of slavery the selling of children from their parents was the worst. My usage as a slave was heaven [compared] to what some others endured. I have witnessed scenes so pathetic that they would move the heart of a stone. And yet when a child was torn away from its mother she never dared to show her grief. Do you wonder that I love the North with its glorious air of freedom? I can never be too thankful that I was brought to Lewiston by Dr. Garcelon. He was a noble man and I revere his memory.”

And who could believe that but a half century ago there were men here in Maine who would have consigned John H. Nichols to perpetual slavery? Truly, truth is stranger than fiction!

Sources: Abbe Museum; Maine Historical Society; Maine Maritime Museum; Northeast Harbor Maritime Museum; Northeast Harbor Library; Penobscot Marine Museum; Maine Granite Industry Historical Society Museum; Escape through the Dismal Swamp (Oct. 2019) davidcecelski.com

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter