The 1st by 17 Years: The Story of Harry S. Murphy,…

Segregated to the Anteroom

Standing Tall Amid the Glares

We Finish to Begin

Give Me An 'A'!

Bertha Josephine Blue

McIntire's Childrens Home Baseball Team

Edith Irby Jones

One Little Girl

Tennessee Town Kindergarten

Julie Hayden

Graduates of Oberlin

A Solitary Figure

Garnet High School Basketball Team

An Invaluable Lesson Outside the Classroom

Undeterred

Spelman Grads Class of 1892

Garnet High School Students

Vivian Malone-Jones

A Revolutionary Hero: Agrippa Hull

First Draftee of WWI: Leo A. Pinckney

Private Redder

The Murder of Henry Marrow

Enslaved No More: Wallace Turnage

Alvin Coffey

John Roy Lynch

A Loving Daughter: Nellie Arnold Plummer

Picking Cotton on Alex Knox's Plantation

From Slavery to Freedom to Prosperity

The Cazenovia Anti-Fugitive Slave Act Convention,…

Mr. and Mrs. Henson

"We Are Literally Slaves" An Early 20th Century B…

Malvina 'Viney' Russell

Elisa Greenwell

Nancy Weston

Lewis Hayden

Josephine Braham Johnson

Mr. and Mrs. Hancock

Behind Union Lines

Isabella Gibbons

William 'Billy' Walker

Addison White

Ezekiel Gillespie

Adam Francis Plummer

Randolph Miller

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

43 visits

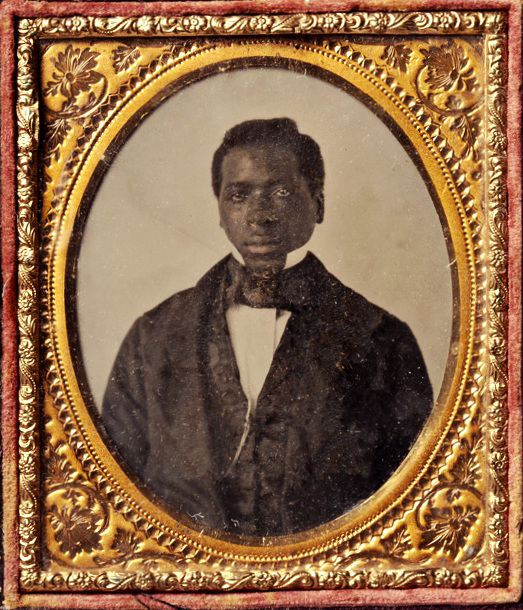

Pedro Tovookan Parris

Parris was born around 1833 on the Eastern coast of Africa, likely in the region of Tanzania or Mozambique. He was abducted when he was about 10 years old during a night raid on his village by a neighboring tribe, according to an early biography. He later recalled seeing his grandmother screaming after him as he was carried away.

Though Congress had outlawed importing slaves in 1808, the slave trade persisted as a fundamental part of the plantation system in the southern United States. Many northerners were involved through trans-Atlantic shipping, manufacturing of goods made with cotton grown in the South and other economic, social and political ties.

Meanwhile, Great Britain, which had outlawed slavery in 1833, was patrolling the Atlantic to block the slave trade from western Africa, which pushed some traders around the Cape of Good Hope to bring slaves from eastern Africa.

Branded and enslaved, Parris traveled to Rio de Janeiro in January 1845 aboard the Porpoise, a leased brig that was built in Brunswick and captained by Cyrus Libby of Scarborough. It was owned by Brunswick businessman George Frost Richardson.

Once in Rio, the disgruntled crew of the Porpoise reported Libby as a slave trader and the ship was seized by George William Gordon, U.S. consul in Brazil.

In a sworn statement recorded by Gordon, Parris said through a translator that he had been treated as a slave, serving at the captain’s table, and had been instructed to say that he was free if anyone ever inquired.

Despite the testimony of Parris and other crew members, Libby was acquitted in 1846. During the trial, Parris got to know Virgil D. Parris, a U.S. marshal and former Maine congressman who took a liking to the friendly boy. When the trial was over, the marshal brought the boy to live at his home in Portland.

Sometime after that, he began calling himself Pedro Tovookan Parris. The first name he likely acquired from Portuguese-speaking slave traders, McNamara said. The middle name is believed to be his original African name. The last name he took from the family that welcomed him when he had few options as a young black man from a foreign country without a family, English skills or work experience.

Exactly what his status was when he lived with the Parrises is unclear. He wasn’t a slave, but he wasn’t exactly free.

Still, the Parrises sent Pedro Tovookan Parris to school, where he learned to read and write English and studied mathematics. He also sang songs from his childhood in Africa and learned to paint, including a 6-foot-long watercolor banner that depicted his journey from Brazil to Maine.

McNamara believes Parris used the banner when he spent six weeks campaigning for George Gordon, the former U.S. consul in Brazil who rescued him from slavery. Gordon ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts in 1856 as a member of the short-lived American or Know-Nothing Party, which opposed slavery and its expansion, as well as immigrants, Catholics and any “foreign pauper” workers who would take jobs away from native-born Americans.

“It was a complicated and tumultuous time in American politics,” McNamara said. “New political parties were rising and established parties were splitting. It’s a period that has real resonance today.”

Parris lived in the house on Paris Hill until his death from pneumonia in April 1860, according to a biography written by Percival J. Parris, who was a boy when the former slave lived with his family. The native of Africa was about 27 years old.

“He was as much attached to the members of the family as they were to him, and he was a general favorite in town,” Percival Parris wrote. “This fact, combined with that of his having been captured as a slave and the strong antislavery sentiment in Maine at that time, probably account for his funeral being one of the most fully attended that had been held in the village.”

An obituary in the local newspaper concluded, “Few have gone from our midst whose loss is more generally or sincerely mourned.” He was buried in the family plot, with a marble marker on his grave. The Civil War started one year later.

“It’s clear that he was fondly embraced by the family and the community, but he was still very much a worker,” McNamara said. “He never established an independent life. I’m just sad he died when he did, because in the years after the Civil War, his life might have taken a whole different route.”

Pedro Tovookan Parris' grave sits off to the side in a private graveyard where the rest of the Parris family is also buried.

Source: Historic New England, Pedro Tovookan Papers; Press Herald "Story of Paris Hill man connects Maine to ‘complexities’ of slave trade," by Kelley Bouchard (July 18, 2018)

Though Congress had outlawed importing slaves in 1808, the slave trade persisted as a fundamental part of the plantation system in the southern United States. Many northerners were involved through trans-Atlantic shipping, manufacturing of goods made with cotton grown in the South and other economic, social and political ties.

Meanwhile, Great Britain, which had outlawed slavery in 1833, was patrolling the Atlantic to block the slave trade from western Africa, which pushed some traders around the Cape of Good Hope to bring slaves from eastern Africa.

Branded and enslaved, Parris traveled to Rio de Janeiro in January 1845 aboard the Porpoise, a leased brig that was built in Brunswick and captained by Cyrus Libby of Scarborough. It was owned by Brunswick businessman George Frost Richardson.

Once in Rio, the disgruntled crew of the Porpoise reported Libby as a slave trader and the ship was seized by George William Gordon, U.S. consul in Brazil.

In a sworn statement recorded by Gordon, Parris said through a translator that he had been treated as a slave, serving at the captain’s table, and had been instructed to say that he was free if anyone ever inquired.

Despite the testimony of Parris and other crew members, Libby was acquitted in 1846. During the trial, Parris got to know Virgil D. Parris, a U.S. marshal and former Maine congressman who took a liking to the friendly boy. When the trial was over, the marshal brought the boy to live at his home in Portland.

Sometime after that, he began calling himself Pedro Tovookan Parris. The first name he likely acquired from Portuguese-speaking slave traders, McNamara said. The middle name is believed to be his original African name. The last name he took from the family that welcomed him when he had few options as a young black man from a foreign country without a family, English skills or work experience.

Exactly what his status was when he lived with the Parrises is unclear. He wasn’t a slave, but he wasn’t exactly free.

Still, the Parrises sent Pedro Tovookan Parris to school, where he learned to read and write English and studied mathematics. He also sang songs from his childhood in Africa and learned to paint, including a 6-foot-long watercolor banner that depicted his journey from Brazil to Maine.

McNamara believes Parris used the banner when he spent six weeks campaigning for George Gordon, the former U.S. consul in Brazil who rescued him from slavery. Gordon ran unsuccessfully for governor of Massachusetts in 1856 as a member of the short-lived American or Know-Nothing Party, which opposed slavery and its expansion, as well as immigrants, Catholics and any “foreign pauper” workers who would take jobs away from native-born Americans.

“It was a complicated and tumultuous time in American politics,” McNamara said. “New political parties were rising and established parties were splitting. It’s a period that has real resonance today.”

Parris lived in the house on Paris Hill until his death from pneumonia in April 1860, according to a biography written by Percival J. Parris, who was a boy when the former slave lived with his family. The native of Africa was about 27 years old.

“He was as much attached to the members of the family as they were to him, and he was a general favorite in town,” Percival Parris wrote. “This fact, combined with that of his having been captured as a slave and the strong antislavery sentiment in Maine at that time, probably account for his funeral being one of the most fully attended that had been held in the village.”

An obituary in the local newspaper concluded, “Few have gone from our midst whose loss is more generally or sincerely mourned.” He was buried in the family plot, with a marble marker on his grave. The Civil War started one year later.

“It’s clear that he was fondly embraced by the family and the community, but he was still very much a worker,” McNamara said. “He never established an independent life. I’m just sad he died when he did, because in the years after the Civil War, his life might have taken a whole different route.”

Pedro Tovookan Parris' grave sits off to the side in a private graveyard where the rest of the Parris family is also buried.

Source: Historic New England, Pedro Tovookan Papers; Press Herald "Story of Paris Hill man connects Maine to ‘complexities’ of slave trade," by Kelley Bouchard (July 18, 2018)

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter