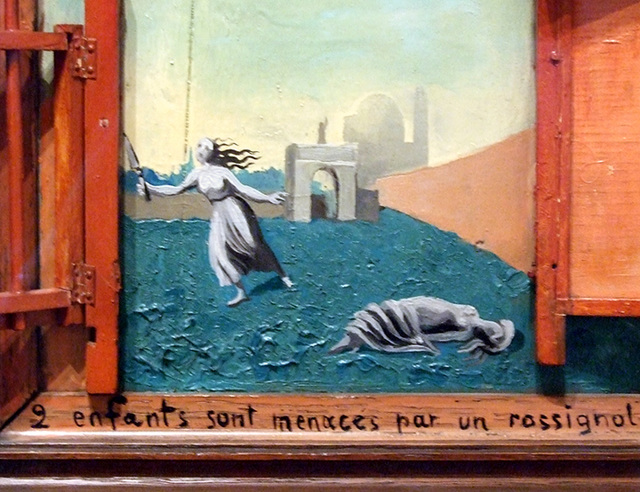

Detail of Two Children are Menanced by a Nightinga…

Detail of the Chariot by Giacometti in the Museum…

The Chariot by Giacometti in the Museum of Modern…

White Cabinet and White Table by Broodthaers in th…

White Cabinet and White Table by Broodthaers in th…

Detail of the Eggs in White Cabinet and White Tabl…

Detail of the Eggs in White Cabinet and White Tabl…

Detail of Street, Dresden by Kirchner in the Museu…

Detail of Street, Dresden by Kirchner in the Museu…

Detail of Street, Dresden by Kirchner in the Museu…

The False Mirror by Magritte in the Museum of Mode…

The False Mirror by Magritte in the Museum of Mode…

Street, Berlin by Kirchner in the Museum of Modern…

Street, Berlin by Kirchner in the Museum of Modern…

Detail of Street, Berlin by Kirchner in the Museum…

Detail of Street, Berlin by Kirchner in the Museum…

Jacques Lipchitz by Diego Rivera in the Museum of…

Grapes by Juan Gris in the Museum of Modern Art, A…

Evening, Honfleur by Seurat in the Museum of Moder…

Detail of Evening, Honfleur by Seurat in the Museu…

Woman Plaiting Her Hair by Picasso in the Museum o…

The Blue Window by Matisse in the Museum of Modern…

L'Estaque by Cezanne in the Museum of Modern Art,…

Goldfish and Sculpture by Matisse in the Museum of…

Fruit Dish by Picasso in the Museum of Modern Art,…

La Japonaise by Matisse in the Museum of Modern Ar…

L'Estaque by Derain in the Museum of Modern Art, A…

L'Estaque by Derain in the Museum of Modern Art, A…

La Japonaise by Matisse in the Museum of Modern Ar…

Playthings of the Prince by DeChirico in the Museu…

Goldfish and Palette by Matisse in the Museum of M…

Goldfish and Palette by Matisse in the Museum of M…

Periwinkles/ Moroccan Garden by Matisse in the Mus…

Subject from a Dyer's Shop by Popova in the Museum…

Woman with a Book by Leger in the Museum of Modern…

Three Musicians by Picasso in the Museum of Modern…

Three Musicians by Picasso in the Museum of Modern…

Seated Bather by Picasso in the Museum of Modern A…

Seated Bather by Picasso in the Museum of Modern A…

The Mirror by Leger in the Museum of Modern Art, A…

The Mirror by Leger in the Museum of Modern Art, A…

Nude with Joined Hands by Picasso in the Museum of…

Nude with Joined Hands by Picasso in the Museum of…

OOF by Edward Ruscha in the Museum of Modern Art,…

Flag by Jasper Johns in the Museum of Modern Art,…

Location

Lat, Lng:

You can copy the above to your favourite mapping app.

Address: unknown

You can copy the above to your favourite mapping app.

Address: unknown

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

900 visits

Detail of Two Children are Menanced by a Nightingale by Ernst in the Museum of Modern Art, August 2007

Max Ernst. (French, born Germany. 1891-1976). Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale. 1924. Oil on wood with painted wood elements and frame, 27 1/2 x 22 1/2 x 4 1/2" (69.8 x 57.1 x 11.4 cm). Purchase.

Gallery label text

Dada, June 18–September 11, 2006

Made in 1924, the year of Surrealism’s founding, Ernst described this work as "the last consequence of his [sic] early collages—and a kind of farewell to a technique..." He later gave two possible autobiographical references for the nightingale: the death of his sister in 1897, and a fevered hallucination he recalled in which the wood grain of a panel near his bed took on "successively the aspect of an eye, a nose, a bird’s head, a menacing nightingale, a spinning top, and so on."

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art , MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 105

In Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, a girl, frightened by the bird's flight (birds appear often in Ernst's work), brandishes a knife; another faints away. A man carrying a baby balances on the roof of a hut, which, like the work's gate (which makes sense in the picture) and knob (which does not), is a three–dimensional supplement to the canvas. This combination of unlike elements, flat and volumetric, extends the collage technique, which Ernst cherished for its "systematic displacement." "He who speaks of collage," the artist believed, "speaks of the irrational." But even if the scene were entirely a painted illusion, it would have a hallucinatory unreality, and indeed Ernst linked his work of this period to childhood memories and dreams.

Ernst was one of many artists who emerged from service in World War I deeply alienated from the conventional values of his European world. In truth, his alienation predated the war; he would later describe himself when young as avoiding "any studies which might degenerate into bread winning," preferring "those considered futile by his professors—predominantly painting. Other futile pursuits: reading seditious philosophers and unorthodox poetry." The war years, however, focused Ernst's revolt and put him in contact with kindred spirits in the Dada movement. He later became a leader in the emergence of Surrealism.

Publication excerpt

John Russell, The Meanings of Modern Art, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1981, p. 206

It was Max Ernst, in 1924, who best fulfilled the Surrealist's mandate. Ernst did it above all in the construction called Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, which starts from one of those instincts of irrational panic which we suppress in our waking lives. Only in dreams can a diminutive songbird scare the daylights out of us; only in dreams can the button of an alarm bell swell to the size of a beach ball and yet remain just out of our reach. Two Children incorporates elements from traditional European painting: perspectives that give an illusion of depth, a subtly atmospheric sky, formalized poses that come straight from the Old Masters, a distant architecture of dome and tower and triumphal arch. But it also breaks out of the frame, in literal terms: the alarm or doorbell, the swinging gate on its hinge and the blind-walled house are three-dimensional constructions, physical objects in the real world. We are both in, and out of, painting; in, and out of, art; in and out of, a world subject to rational interpretation. Where traditional painting subdues disbelief by presenting us with a world unified on its own terms, Max Ernst in the Two Children breaks the contract over and over again. We have reason to disbelieve the plight of his two children. Implausible in itself, it is set out in terms which eddy between those of fine art and those of the toyshop. Nothing "makes sense" in the picture. Yet the total experience is undeniably meaningful; Ernst has re-created a sensation painfully familiar to us from our dreams but never before quite recaptured in art—that of total di

Gallery label text

Dada, June 18–September 11, 2006

Made in 1924, the year of Surrealism’s founding, Ernst described this work as "the last consequence of his [sic] early collages—and a kind of farewell to a technique..." He later gave two possible autobiographical references for the nightingale: the death of his sister in 1897, and a fevered hallucination he recalled in which the wood grain of a panel near his bed took on "successively the aspect of an eye, a nose, a bird’s head, a menacing nightingale, a spinning top, and so on."

Publication excerpt

The Museum of Modern Art , MoMA Highlights, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, revised 2004, originally published 1999, p. 105

In Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, a girl, frightened by the bird's flight (birds appear often in Ernst's work), brandishes a knife; another faints away. A man carrying a baby balances on the roof of a hut, which, like the work's gate (which makes sense in the picture) and knob (which does not), is a three–dimensional supplement to the canvas. This combination of unlike elements, flat and volumetric, extends the collage technique, which Ernst cherished for its "systematic displacement." "He who speaks of collage," the artist believed, "speaks of the irrational." But even if the scene were entirely a painted illusion, it would have a hallucinatory unreality, and indeed Ernst linked his work of this period to childhood memories and dreams.

Ernst was one of many artists who emerged from service in World War I deeply alienated from the conventional values of his European world. In truth, his alienation predated the war; he would later describe himself when young as avoiding "any studies which might degenerate into bread winning," preferring "those considered futile by his professors—predominantly painting. Other futile pursuits: reading seditious philosophers and unorthodox poetry." The war years, however, focused Ernst's revolt and put him in contact with kindred spirits in the Dada movement. He later became a leader in the emergence of Surrealism.

Publication excerpt

John Russell, The Meanings of Modern Art, New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1981, p. 206

It was Max Ernst, in 1924, who best fulfilled the Surrealist's mandate. Ernst did it above all in the construction called Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale, which starts from one of those instincts of irrational panic which we suppress in our waking lives. Only in dreams can a diminutive songbird scare the daylights out of us; only in dreams can the button of an alarm bell swell to the size of a beach ball and yet remain just out of our reach. Two Children incorporates elements from traditional European painting: perspectives that give an illusion of depth, a subtly atmospheric sky, formalized poses that come straight from the Old Masters, a distant architecture of dome and tower and triumphal arch. But it also breaks out of the frame, in literal terms: the alarm or doorbell, the swinging gate on its hinge and the blind-walled house are three-dimensional constructions, physical objects in the real world. We are both in, and out of, painting; in, and out of, art; in and out of, a world subject to rational interpretation. Where traditional painting subdues disbelief by presenting us with a world unified on its own terms, Max Ernst in the Two Children breaks the contract over and over again. We have reason to disbelieve the plight of his two children. Implausible in itself, it is set out in terms which eddy between those of fine art and those of the toyshop. Nothing "makes sense" in the picture. Yet the total experience is undeniably meaningful; Ernst has re-created a sensation painfully familiar to us from our dreams but never before quite recaptured in art—that of total di

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

Sign-in to write a comment.