Charles Darwin

Darwin's study

Darwin

Branch

Man's Oneness with Nature

Hegel

No news is good news

Revolution in Europe

KARL MARX

POLARIZATION OF THE CLASSES

The Means of subsistence

The POWER of IDEAS

SHACKLED BY VALUE SYSTESM

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Yo, Ho, Neighbour....!

BERTRAND RUSSELL

Checking the Facts

LIVING TO THE FULL

Auto

Church

Prayer

Beagle

Beagle

Charles Darwin

What is a Primitive World

Down House

Darwin's old study at Down

Mirror Test

The LEGACY of SCHOPENHAUER

ABOVE AND BEYOND

Representation and Reality

THE NATURE OF EXPERIENCE

DECLARATIONS OF THE RIGHTS OF MAN

INTELLECTUALS GATHERING AT THE CAFE D'ALEXANDRE, P…

THE STROMING OF THE BASTIEEL

A LADY AT HER MIRROR, JEAN RAOUX (1720s)

RULED BY THE HEART

YALE UNIVERISTY

Knowledge of the External World

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

63 visits

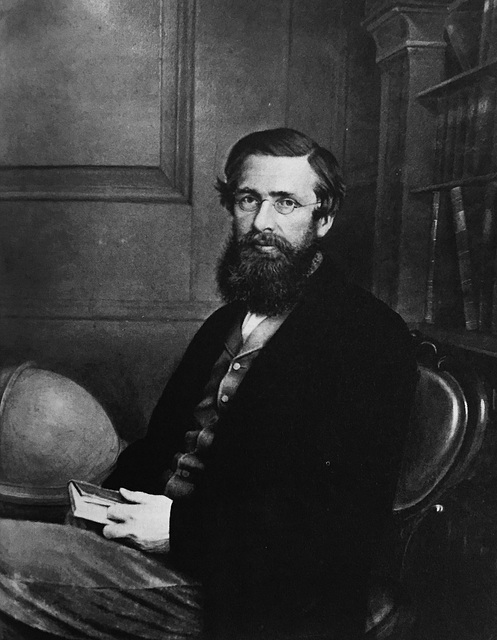

Alfred Wallace, aged 46, in 1869

Erhard Bernstein, Paolo Tanino have particularly liked this photo

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

After arrival in Singapore in April 1854 Wallace collected briefly in the highlands near Malacca while learning to speak Malay, and then moved on to Borneo, where he was the guest of Sir James Brooke en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Brooke#:~:text=Sir%20James%20Brooke%2C%20Rajah%20of,until%20his%20death%20in%201868. In a burst of private enterprise at the turn of the century Sir James had taken possession of Sarawak, a territory on the north west Coast of the island, where he had set himself up as the first of what would prove to be a long line of white rajahs. Wallace was delighted to stay in the rajah’s court while engaging guides and preparing for his expedition into th interior. Moreover, the elderly Sir James much enjoyed company of this intelligent, well informed young man, whose tongue was loosed in this less than expert company. ‘He pleased, instructed and delighted us by his clever and inexhaustible flow of talk -- really good talk,’ the rajah’s secretary recalled. “The Rajah was pleased to have so clever a man with him and it excited his mind and brought out his brilliant ideas. A favorite topic, apparently, was evolution

During one or two excursions up country to collect specimens, Wallace occasionally stayed I a Dyak long-house thespicerouteend.com/dayak-longhouse-kapuas-putussibau-kalimantan enjoying the lively and helpful way in which such a large number of families succeeded in livingly amicably together. When he was temporarily immoblised by the rainy season and lent a little house by the rajah, Wallace began to ponder over the problem which, he later reported, ‘was rarely absent’ from his thought. No one, it seemed had thought of combining facts about geographical distribution, his own speciality, with facts about the succession of species in time, so well presented by Lyell, in the hope of casting light on the way in which species had come into existence. He therefore drafted an easy entitled ‘On the Law which has regulated the Introduction of New Species’, and early in 1855 sent it off by the mailboat via Singapore toLondon, addressed to the editor of ‘The Annals and Magazine of Natural History’ There it duly appeared in September that year. In lucid, cogent prose, Wallace had reviewed all the geographical and geological evidence pointing to the historical occurrene of evolution. He had ventured nothing, however, on how evolution might have proceeded. Although Darwin was an avid reader of journals, he seems not have seen this number and it was lef to Lyell to draw his attention to it. Hardly anyone else in England was the least interested, however, and such news as reached Wallace from his agent suggested it had fallen completely flat. ~ Page 324

There followed for Darwin an appalling conflict between his desire for priority and fame and his sense of honour. Wallace’s paper clearly deserved publication and this he must arrange. At the same time his own 1844 essay, read by Hooker many years previously, showed that he had developed the very said ideas independently of Wallace. Yet he had had no plans to publish anything until his big book was complete. Would it therefore be honourable to rush into print now? . . . .

The solution to the dilemma is well known Lyell and Hooker, though keenly alive to darwin’s twenty years gestation, ruled it a dead-heat. Wallace’s papers together with an extract from Darwin’s essay (with part of the sketch he had sent Asa Gray the previous autumn) should be presented together as a meeting of the Linnean Society and then published in its journal. . . . . Both Lyell and Hooker spoke briefly, impressing on the audience the need to give the papers serious attention; ‘but’ in Hooker’s words:

there was no semblance of discussion. The interest excited was intense, but the subject too novel and too ominous for the Old School to enter the lists before armouring. It was talked over after the meeting, ‘with bated breath’. Lyell’s approval, and perhaps in a small way mine, as his lieutenant in the affair, rather overawed those Fellows who would otherwise have flown out against the doctrine, and this because we have th vantage ground of being familiar with the authors and their themes.

Publication took place the following August. Thereafter, when writing to Wallace, Darwin always referred to “out theory’. Conversely Wallace keenly aware of th twenty years during which Darwin had been working on the problem and collecting the evidence, never failed to give precedence to Darwin. They became close friends, and their correspondence reveals how many were their agreements and how unexpected their few differences. Thus ended one of the happiest stories in the history of science. ~ Page 332

people.wku.edu/charles.smith/wallace/S301.htm

Using this principle of adaptive parsimony, Wllace felt that the human brain was far more advanced, more capable of feats of gratuitous complexity, than our ancestors could have required. He was stuck by the fact, for example that individuals of the “barbarian races,” exposed to the intellectual extravagances of European civilization quickly rose to the occasion, becoming fluent in new languages, capable of absorbing the accoutrements of high society and elaborate refinement of Victorian art, music, literature, and the like.

In 1869, Wallace wrote that “natural selection could only have endowed the savate with a brain a little superior to that of an ape, whereas he actually possesses one but very little inferior to that of the average member of our learned societies.” The problem, as Wallace saw it, was that the human brain appears to be “an instrument. . . developed in advance of the needs of its possessor.” His evidence was the fact that “savages” -- given the opportunity -- could learn to grasp European music, art, literature, and philosophy , and yet they didn’t employ these subtleties in their own, natural state. ~ Page142