Another Forgotten Lady: Ida Forsyne

The Well

Norton & Margot

Aida Overton Walker

Etta Moten Barnett

Dora Dean of Johnson & Dean

Their Act Packed A Wallop

First Black Actress to win an Emmy for Outstanding…

Florence Mills

Margot Webb

The first 'Carmen Jones' Muriel Smith

Theodore Drury

Elizabeth Welch

Diana Sands

Sheila Guyse

Angelina Weld Grimké

The First Black Child Movie Star

Judy Pace

Mamie Flowers: The Bronze Melba

Inventor of Tap: William Henry Juba

Charles S Gilpin

Birdie Gilmore

John W. Isham's The Octoroons

Sir Duke's Baby Sis: Ruth Ellington

A Fool And His Money: Earliest Surviving American…

Joseph Downing

Dudley and Grady

Abbie Mitchell

Claudia McNeil

The Great Florence Mills

Billy Kersands

Isabel Washington

James Baldwin

Pearl Hobson

In Memoriam: Minnie Brown

Anita Reynolds: A Life Unpublished

Edna Alexander

The 4 Black Diamonds

William 'Billy' McClain

Hattie McIntosh

Hiding in Plain Site: Joveddah de Rajah & Co.

Aida Overton Walker

Frederick J Piper

Hyers Sisters

Barbara McNair

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

39 visits

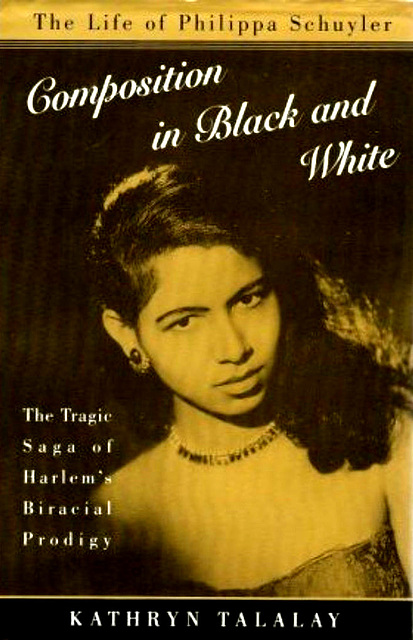

Philippa Schuyler

So Young, So Gifted, So Sad

The Washington Post

Article By Carolyn See

Bruno Bernard, Photographer

Nov. 24, 1995

This one's a heartbreaker. This one will make you wring your hands about America, what it means to be a woman, and what it means to be black. In case you ever harbored any utopian ideals about how -- with hard work and good intentions -- we might make this a better country, this book will certainly disabuse you of any daydreams in that regard. Also, if you ever had any mushy, personal thoughts about fame -- how, if you ever managed to get your picture in Time magazine, you could transcend your own personal history and achieve a secular heaven of success -- this book will disabuse you of that, too.

Philippa Duke Schuyler was born in 1931 to a black journalist father and a wealthy Southern white mother who sold themselves on the idea that only by miscegenation could the race question in America be solved. (Or, more accurately, Josephine, the mom, wrote that down in her diary. George Schuyler may have had another whole agenda.) Josephine had gone from man to man and wanted to make a statement, put some kind of meaning in her life. She married that black man, scandalized her folks, fed her daughter on raw liver and brains and began keeping scrapbooks on her "hybrid experiment."

The raw liver must have worked because in no time Philippa was walking, talking, reading, writing. Her IQ tested out at 180, and by age 4 she was playing Mozart. Her dad was already fooling around with the ladies, but her mother had found her life's work, the creation of a musical genius.

Here, Philippa's story takes a terrible turn. Her mother whipped her regularly. She never had any friends because she hardly ever got to go to school. When she did go, she was years ahead of the other kids, and she was the only person "of color" for miles around. Thanks to her journalist father, she had her picture in the magazines as a talented "Negro" prodigy, but in day-to-day life it was only Philippa and her mother, locked in an isolated, manipulative struggle. Even her piano teachers, who might have offered her various windows onto the world, were dismissed by her mother as soon as there was any emotional attachment between them and Philippa.

The prodigy and her mother went on tour. The reviews were almost always good. But both Philippa and her mother were incredibly slow learners about the nature of the outside world: As a woman, Philippa would have a terribly hard time making it as a concert pianist; as a mulatto she would find it almost impossible. She would do well enough as a child prodigy, but there would come a time when she would hit the wall.

Had her mother turned out a genius or a freak of nature? Kathryn Talalay, the author of this sad and thoughtful biography, doesn't jump to conclusions; she just lets the story play out. When Philippa is presented, in her early teens, with the scrapbooks that chronicle her life, she's horrified; she understands that from her parents' point of view, she's been a genetic experiment. She can't even take credit for her own "genius" since her mother has been so relentlessly pulling the strings in her life. But she has no recourse; her whole existence has been playing the piano, dolling up in the spotlight and then either working for, with, or against her mother. There is no way out.

After Philippa is grown, her touring takes her through South America, Europe, Africa. She's well received, but her life is at once adventurous and intensely narrow. She rarely has the time to have fun or even see where she's touring. In Africa, she's tormented by all that it means to be black. She sees women toiling, disregarded, disrespected. Indeed, as time goes by, she decides she really isn't black. "I am not a Negro!" she writes her mother, and using mental sleight-of-hand, she decides that her father came from Madagascar, and that she's really "Malay-American-Indian and European."

So desperate was she not to be "colored" that she took out a passport in another name, Felipa Monterro y Schuyler, suggesting that she had an Iberian heritage. Her politics had by this time become so strange that she lectured regularly to the John Birch Society. She had strings of suitors who treated her badly, and the one man who loved her she couldn't abide. She was, in a phrase, totally screwed up. She was unable to resolve the elements of black and white in her own life, unable to shake off her demon mother, unable to love or be loved. She died in 1967 in a helicopter accident in Vietnam, where she had gone in her new career as a reporter. And yet, for hundreds, thousands of black kids in the '40s and '50s, she was a role model, a reason to take piano lessons. This is a bleak, extraordinarily weird American life. Kathryn Talalay has done a gorgeous job with this unique material.

The Washington Post

Article By Carolyn See

Bruno Bernard, Photographer

Nov. 24, 1995

This one's a heartbreaker. This one will make you wring your hands about America, what it means to be a woman, and what it means to be black. In case you ever harbored any utopian ideals about how -- with hard work and good intentions -- we might make this a better country, this book will certainly disabuse you of any daydreams in that regard. Also, if you ever had any mushy, personal thoughts about fame -- how, if you ever managed to get your picture in Time magazine, you could transcend your own personal history and achieve a secular heaven of success -- this book will disabuse you of that, too.

Philippa Duke Schuyler was born in 1931 to a black journalist father and a wealthy Southern white mother who sold themselves on the idea that only by miscegenation could the race question in America be solved. (Or, more accurately, Josephine, the mom, wrote that down in her diary. George Schuyler may have had another whole agenda.) Josephine had gone from man to man and wanted to make a statement, put some kind of meaning in her life. She married that black man, scandalized her folks, fed her daughter on raw liver and brains and began keeping scrapbooks on her "hybrid experiment."

The raw liver must have worked because in no time Philippa was walking, talking, reading, writing. Her IQ tested out at 180, and by age 4 she was playing Mozart. Her dad was already fooling around with the ladies, but her mother had found her life's work, the creation of a musical genius.

Here, Philippa's story takes a terrible turn. Her mother whipped her regularly. She never had any friends because she hardly ever got to go to school. When she did go, she was years ahead of the other kids, and she was the only person "of color" for miles around. Thanks to her journalist father, she had her picture in the magazines as a talented "Negro" prodigy, but in day-to-day life it was only Philippa and her mother, locked in an isolated, manipulative struggle. Even her piano teachers, who might have offered her various windows onto the world, were dismissed by her mother as soon as there was any emotional attachment between them and Philippa.

The prodigy and her mother went on tour. The reviews were almost always good. But both Philippa and her mother were incredibly slow learners about the nature of the outside world: As a woman, Philippa would have a terribly hard time making it as a concert pianist; as a mulatto she would find it almost impossible. She would do well enough as a child prodigy, but there would come a time when she would hit the wall.

Had her mother turned out a genius or a freak of nature? Kathryn Talalay, the author of this sad and thoughtful biography, doesn't jump to conclusions; she just lets the story play out. When Philippa is presented, in her early teens, with the scrapbooks that chronicle her life, she's horrified; she understands that from her parents' point of view, she's been a genetic experiment. She can't even take credit for her own "genius" since her mother has been so relentlessly pulling the strings in her life. But she has no recourse; her whole existence has been playing the piano, dolling up in the spotlight and then either working for, with, or against her mother. There is no way out.

After Philippa is grown, her touring takes her through South America, Europe, Africa. She's well received, but her life is at once adventurous and intensely narrow. She rarely has the time to have fun or even see where she's touring. In Africa, she's tormented by all that it means to be black. She sees women toiling, disregarded, disrespected. Indeed, as time goes by, she decides she really isn't black. "I am not a Negro!" she writes her mother, and using mental sleight-of-hand, she decides that her father came from Madagascar, and that she's really "Malay-American-Indian and European."

So desperate was she not to be "colored" that she took out a passport in another name, Felipa Monterro y Schuyler, suggesting that she had an Iberian heritage. Her politics had by this time become so strange that she lectured regularly to the John Birch Society. She had strings of suitors who treated her badly, and the one man who loved her she couldn't abide. She was, in a phrase, totally screwed up. She was unable to resolve the elements of black and white in her own life, unable to shake off her demon mother, unable to love or be loved. She died in 1967 in a helicopter accident in Vietnam, where she had gone in her new career as a reporter. And yet, for hundreds, thousands of black kids in the '40s and '50s, she was a role model, a reason to take piano lessons. This is a bleak, extraordinarily weird American life. Kathryn Talalay has done a gorgeous job with this unique material.

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter