Lauretta Green Butler

Daisy Turner

Emma Louise Hyers

Walker & May

McIntosh and King

Mae Virginia Cowdery

Pearl Hobson

Billie Allen

Gertrude Saunders

Valaida Snow: Overlooked No More

Hyers Sisters: Emma and Anna

Arabella Fields: The Black Nightingale

Marion Smart

Lorain High School Yearbook Photo

Lillian Evanti in Costume as Lakmé

Jackie Ormes: Creator of Torchy Brown

Queen of Swing: Norma Miller

Cole and Wiley

Barbara McNair

Hyers Sisters

Frederick J Piper

Aida Overton Walker

Hiding in Plain Site: Joveddah de Rajah & Co.

Bessie L Gillam

Something Good Negro Kiss

Aida Overton Walker

Juanita Moore

Drag King: Miss Florence Hines

Mattie Wilkes

The Josephine Baker of Berlin: Ruth Bayton

Katherine Dunham performing in Floyd's Guitar Blue…

She Made Cartoon TV History: Patrice Holloway

Oscar Micheaux: America's First Black Director

Aida Overton Walker

Ernest Hogan

W. Henry Thomas

Jennie Scheper

Gertrude Saunders

An Easter Lily

The Creole Nightingale

Arabella Fields: The Black Nightingale

The Cakewalking Couple: Johnson and Dean

Anna Madah Hyers

Eartha Kitt

The Magicians: Armstrong Family

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

35 visits

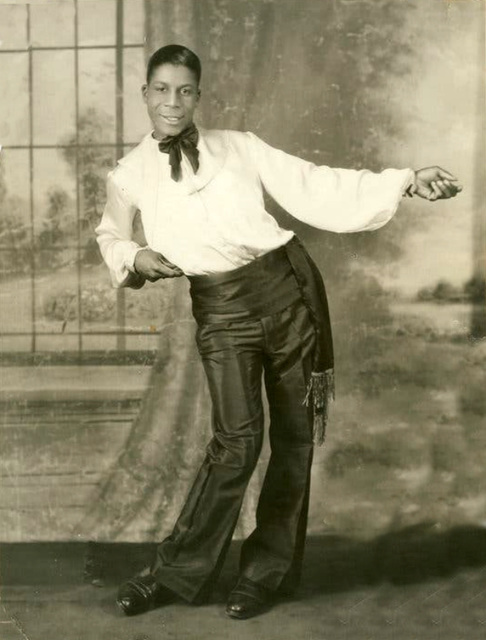

Snakehips: Earl Tucker

Overlooked is a series of obituaries about remarkable people whose deaths, beginning in 1851, went unreported in The New York Times.

There are many mysteries about the dancer Earl Tucker, but the meaning of his stage name isn’t one of them. To understand why he was called Snakehips, you have only to watch him move.

Take his solo routine in the 1930 short film “Crazy House.” About 30 seconds in, Tucker rolls his hips to one side. He rolls them so far that his torso tilts in counterbalance, his ankles sickle over, and his whole body bends into an S-curve of improbable depth.

He reverses the shape — first churning slowly, then at twice and four times the speed, the smaller, quicker undulations making him slither sideways on one foot. His trailing leg embroiders the glide with lariat-like curlicues, but what draws a viewer’s eye, hypnotically, is the motor: the spiraling, snaking motion of those hips.

By the time he appeared in the film, Snakehips Tucker was already a name attraction in Harlem nightclubs like the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn, and he had appeared to acclaim on Broadway and in Paris. He died on May 14, 1937, when he was just thirty-one.

The cause, as described in his obituary in The Baltimore Afro-American, was a “mysterious illness.” Neither that obituary nor those in other African-American newspapers — the mainstream press did not report the death — included many biographical facts about Tucker. Back then, obscurity wasn’t unusual for black entertainers, but the articles praised him as one of the most imitated artists of the day.

Tucker’s influence didn’t end with his death. Elvis Presley, who was born two years before Tucker died, probably never saw him dance, yet he scandalized 1950s America with a more timid version of Tucker’s below-the-waist action, making girls in the audience scream. Elvis the Pelvis also took on the moniker “Ol’ Snakehips.”

Later, Tucker’s loose kicks and unwinding spins found an echo in the signature moves of Michael Jackson. Some hip-hop dancers who came across video footage of Tucker were said to have experienced a shock of recognition: This guy was doing some of their steps decades before they were.

Even if these dancers didn’t imitate Tucker directly, they drew on a style that he had heightened and popularized. He could also tap dance and do the Charleston, but it was the hip rotations and the shaking that distinguished him from black male dancers of his day, in part because the moves were associated with the sexually charged ones of female dancers; “shake” dancers were known to shimmy and grind.

(This gender distinction still held when Elvis came on the scene, prompting hostile journalists to liken him disparagingly to burlesque ladies doing the hoochie coochie.)

Duke Ellington, who hired Tucker to dance with his band at the Cotton Club and elsewhere, once speculated that Tucker had come from “tidewater Maryland, one of those primitive lost colonies where they practice pagan rituals and their dancing style evolved from religious seizures.”

Tucker was, in fact, discovered in Maryland, dancing in the streets of Baltimore, and Ellington’s claim is probably accurate in other ways: What Ellington called “pagan rituals,” scholars would identify as African spiritual practices that informed African-American culture. Tucker’s trembling was most likely related to dances of spiritual possession, which became part of Pentecostal, Sanctified and Holiness traditions.

In the film “Crazy House,” Tucker does his shaking while rubbing his hands together, as if he were shivering in the cold while skating on ice. The addition of sleigh bells to the bouncy music underlined the idea.

Whatever its source, his dancing was entertainment that played to the illicit appeal of Harlem nightclubs. (Ellington’s art was promoted as “jungle music.”) When Tucker appeared on Broadway in the all-black revue “Blackbirds of 1928,” the program described his act as his “conception of the low down dance.”

That low-down quality was in contrast to the upright tapping of the show’s star, Bill Robinson. Zora Neale Hurston, in her now-canonical 1934 essay “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” cited only two dancers by name: Robinson and Tucker. She used both as exemplars of the “lack of symmetry that makes Negro dancing so difficult for white dancers to learn.”

But it’s easy to imagine that Hurston was still thinking of Tucker when she wrote: “Negro dancing is dynamic suggestion. No matter how violent it may appear to the beholder, every posture gives the impression that the dancer will do much more.”

Reviewers tended to describe Tucker’s “double-jointed” dancing with euphemisms or expressions of disbelief. (His death may have been shrouded in euphemisms, too; “mysterious illness” was sometimes code for syphilis.) It took a French critic — who was less squeamish about sex and had different attitudes about race — to hail Tucker as “a marvelous artist who knows all the dances of the universe.”

The best information about Tucker comes from the interviews with black entertainers that Marshall and Jean Stearns conducted in the 1960s for their seminal book “Jazz Dance” (1968). Marshall Stearns himself could remember his embarrassment when, as a white college student in the late-1920s, he took a date to hear Ellington’s band at the Cotton Club and encountered the “murderously naughty” Tucker. He spent most of his energy “trying not to look shocked,” he said.

Writing in the more freewheeling cultural context of the 1960s, Stearns mocked that response as puritanical; citing the mambo and rock ’n’ roll dances, he judged that Tucker’s pelvic skill had come “too early.”

Today, Tucker’s dancing would be considered less disturbing than other aspects of his behavior. The entertainers interviewed by the Stearnses remembered Snakehips as a heavy gambler and “a mean guy” with a violent temper who was nevertheless popular with women. Newspaper reports about the “bad boy of Harlem” covered his arrests as often as his performances.

In one instance he was charged with stabbing a fellow gambler in the abdomen with a penknife. Another time, the charge was “forcing his attentions” on a 15-year-old girl. Yet another time, it was rape. All these charges seem to have been dropped, as was the assault charge filed by his dance partner, Bessie Dudley. A few years later, newspapers reported that he had stabbed the performer Lavinia Mack, and that she had stabbed him back.

A gossip columnist for The Pittsburgh Courier wrote — falsely — that Tucker died from that stabbing. It must have seemed true to Tucker’s character that he would meet his end in such a violent manner. Whatever the cause, when he died, he left behind his wife and a 10-year-old son.

What remains, beyond these fragmented memories, are a few seconds of him at the end of the 1935 musical short “Symphony in Black” and his two-minute routine in “Crazy House,” a comedy set in the Lame Brain Sanitarium. He doesn’t look so menacing there. His snaps and claps draw attention to a musicality that runs through all his hip rolling, through his every sinking to the ground and miraculously rubbery recovery. He wasn’t a contortionist. He was a dancer, one of a kind.

Tucker's style of dancing in a 1935 musical short called "Symphony in Black" www.youtube.com/watch?v=7U4ww-MmAY4&t=49s

Source: New York Times: Overlooked No More (article written by Brian Seibert) Dec. 18, 2019

There are many mysteries about the dancer Earl Tucker, but the meaning of his stage name isn’t one of them. To understand why he was called Snakehips, you have only to watch him move.

Take his solo routine in the 1930 short film “Crazy House.” About 30 seconds in, Tucker rolls his hips to one side. He rolls them so far that his torso tilts in counterbalance, his ankles sickle over, and his whole body bends into an S-curve of improbable depth.

He reverses the shape — first churning slowly, then at twice and four times the speed, the smaller, quicker undulations making him slither sideways on one foot. His trailing leg embroiders the glide with lariat-like curlicues, but what draws a viewer’s eye, hypnotically, is the motor: the spiraling, snaking motion of those hips.

By the time he appeared in the film, Snakehips Tucker was already a name attraction in Harlem nightclubs like the Cotton Club and Connie’s Inn, and he had appeared to acclaim on Broadway and in Paris. He died on May 14, 1937, when he was just thirty-one.

The cause, as described in his obituary in The Baltimore Afro-American, was a “mysterious illness.” Neither that obituary nor those in other African-American newspapers — the mainstream press did not report the death — included many biographical facts about Tucker. Back then, obscurity wasn’t unusual for black entertainers, but the articles praised him as one of the most imitated artists of the day.

Tucker’s influence didn’t end with his death. Elvis Presley, who was born two years before Tucker died, probably never saw him dance, yet he scandalized 1950s America with a more timid version of Tucker’s below-the-waist action, making girls in the audience scream. Elvis the Pelvis also took on the moniker “Ol’ Snakehips.”

Later, Tucker’s loose kicks and unwinding spins found an echo in the signature moves of Michael Jackson. Some hip-hop dancers who came across video footage of Tucker were said to have experienced a shock of recognition: This guy was doing some of their steps decades before they were.

Even if these dancers didn’t imitate Tucker directly, they drew on a style that he had heightened and popularized. He could also tap dance and do the Charleston, but it was the hip rotations and the shaking that distinguished him from black male dancers of his day, in part because the moves were associated with the sexually charged ones of female dancers; “shake” dancers were known to shimmy and grind.

(This gender distinction still held when Elvis came on the scene, prompting hostile journalists to liken him disparagingly to burlesque ladies doing the hoochie coochie.)

Duke Ellington, who hired Tucker to dance with his band at the Cotton Club and elsewhere, once speculated that Tucker had come from “tidewater Maryland, one of those primitive lost colonies where they practice pagan rituals and their dancing style evolved from religious seizures.”

Tucker was, in fact, discovered in Maryland, dancing in the streets of Baltimore, and Ellington’s claim is probably accurate in other ways: What Ellington called “pagan rituals,” scholars would identify as African spiritual practices that informed African-American culture. Tucker’s trembling was most likely related to dances of spiritual possession, which became part of Pentecostal, Sanctified and Holiness traditions.

In the film “Crazy House,” Tucker does his shaking while rubbing his hands together, as if he were shivering in the cold while skating on ice. The addition of sleigh bells to the bouncy music underlined the idea.

Whatever its source, his dancing was entertainment that played to the illicit appeal of Harlem nightclubs. (Ellington’s art was promoted as “jungle music.”) When Tucker appeared on Broadway in the all-black revue “Blackbirds of 1928,” the program described his act as his “conception of the low down dance.”

That low-down quality was in contrast to the upright tapping of the show’s star, Bill Robinson. Zora Neale Hurston, in her now-canonical 1934 essay “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” cited only two dancers by name: Robinson and Tucker. She used both as exemplars of the “lack of symmetry that makes Negro dancing so difficult for white dancers to learn.”

But it’s easy to imagine that Hurston was still thinking of Tucker when she wrote: “Negro dancing is dynamic suggestion. No matter how violent it may appear to the beholder, every posture gives the impression that the dancer will do much more.”

Reviewers tended to describe Tucker’s “double-jointed” dancing with euphemisms or expressions of disbelief. (His death may have been shrouded in euphemisms, too; “mysterious illness” was sometimes code for syphilis.) It took a French critic — who was less squeamish about sex and had different attitudes about race — to hail Tucker as “a marvelous artist who knows all the dances of the universe.”

The best information about Tucker comes from the interviews with black entertainers that Marshall and Jean Stearns conducted in the 1960s for their seminal book “Jazz Dance” (1968). Marshall Stearns himself could remember his embarrassment when, as a white college student in the late-1920s, he took a date to hear Ellington’s band at the Cotton Club and encountered the “murderously naughty” Tucker. He spent most of his energy “trying not to look shocked,” he said.

Writing in the more freewheeling cultural context of the 1960s, Stearns mocked that response as puritanical; citing the mambo and rock ’n’ roll dances, he judged that Tucker’s pelvic skill had come “too early.”

Today, Tucker’s dancing would be considered less disturbing than other aspects of his behavior. The entertainers interviewed by the Stearnses remembered Snakehips as a heavy gambler and “a mean guy” with a violent temper who was nevertheless popular with women. Newspaper reports about the “bad boy of Harlem” covered his arrests as often as his performances.

In one instance he was charged with stabbing a fellow gambler in the abdomen with a penknife. Another time, the charge was “forcing his attentions” on a 15-year-old girl. Yet another time, it was rape. All these charges seem to have been dropped, as was the assault charge filed by his dance partner, Bessie Dudley. A few years later, newspapers reported that he had stabbed the performer Lavinia Mack, and that she had stabbed him back.

A gossip columnist for The Pittsburgh Courier wrote — falsely — that Tucker died from that stabbing. It must have seemed true to Tucker’s character that he would meet his end in such a violent manner. Whatever the cause, when he died, he left behind his wife and a 10-year-old son.

What remains, beyond these fragmented memories, are a few seconds of him at the end of the 1935 musical short “Symphony in Black” and his two-minute routine in “Crazy House,” a comedy set in the Lame Brain Sanitarium. He doesn’t look so menacing there. His snaps and claps draw attention to a musicality that runs through all his hip rolling, through his every sinking to the ground and miraculously rubbery recovery. He wasn’t a contortionist. He was a dancer, one of a kind.

Tucker's style of dancing in a 1935 musical short called "Symphony in Black" www.youtube.com/watch?v=7U4ww-MmAY4&t=49s

Source: New York Times: Overlooked No More (article written by Brian Seibert) Dec. 18, 2019

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter