Carlotta Stewart-Lai

Lille Belle Armstrong

Vintage Lady

Mattie McGhee

Vintage Woman

Lucy Davis

Vintage Miss

Vintage Lady

Young Miss

Octavia Parker Ferguson

Mildred Hanson Baker

Memories

Lady and her Companion

Miss Nelly Hill

Vintage Miss

Vintage Ladies

Vintage Lady

Vintage Lady

Vintage Lady

Vintage Lady

Vintage Woman

Hand Painted Miss

Vintage Miss

Tate Travel Club

Detroit's Wall of Shame

No Rest for the Weary

The Crossing Guard

Easy Rider

Mr. Harris

An Engaging Couple

Vintage Couple

Vintage Couple

Vintage Couple

Cap n Kid

Sallie Venning Holden and Louise Venning

Jacob and Sophia Redder

Sheppard Family

Vintage Couple

Alexander Four

Vintage Couple

Sepia Couple

Family Portrait

Sisters in Sepia

Kim and Jennie

The Powell Men

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

56 visits

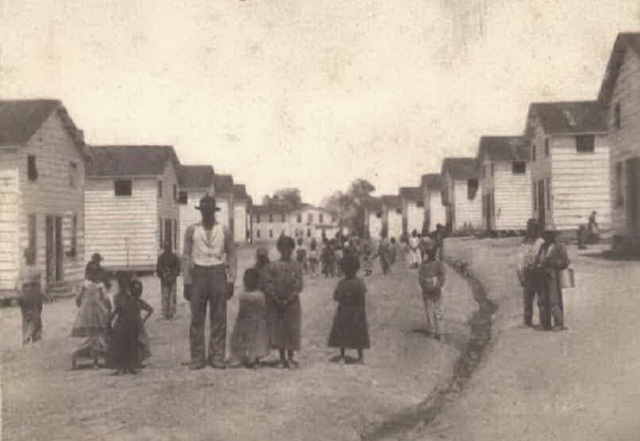

Freedman's Village

African American residents of the Freedman's Village in Arlington, Virginia.

Charter buses roll up to Arlington National Cemetery every day, depositing tourists who scramble uphill to see the eternal flame on President John F. Kennedy's grave. People stream in all directions, toward the Tomb of the Unknowns or to remember at tombstones of loved ones lost to war. Few, however, head downhill to a quiet corner near the Iwo Jima Memorial.

There are no memorials to ancient battles, no ornate headstones honoring long-dead dignitaries. There are only rows of small unassuming white tombstones, many engraved with names like George, Toby and Rose. They are the only visible reminders that part of the nation's most storied burial ground sits atop what used to be a thriving black town — "Freedman's Village," built on land confiscated from Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. There's nothing there now to tell visitors that formerly enslaved men, women and children once lived there.

Arlington National Cemetery was established on land confiscated from Lee and his family in 1861 after the general took command of the Confederate forces. The Civil War leaders of the Union buried dead soldiers on the property in hopes that Lee would never want to return. The federal government turned some land about half a mile north of Lee's mansion into a town specifically for freed slaves, referred to as contraband, who had nowhere to go.

Freedman's Village was no ramshackle camp. At its height, more than 1,100 former slaves lived in a collection of 50 one-and-a-half story duplexes surrounding a central pond. Although the town was supposed to be temporary, the freed slaves put up churches, stores, a hospital, mess hall, a school, an "old people's home" and a laundry — to make a life for themselves. "I think it would have very much resembled a town anywhere in America today with that population. They had the same needs as anywhere, and they sustained themselves by working," said Thomas Sherlock, historian at Arlington National Cemetery.

Living in Freedman's Village wasn't free. Workers with government jobs on nearby farms or those doing construction were paid $10 a week, but half their salary was turned over to the federal government to pay for running the town. Everyone else who lived on site was charged between $1 and $3 rent.

Dignitaries from around the nation came to see — and sometimes stay — with residents. The most famous was Sojourner Truth, the fiery black abolitionist and preacher, who spent about a year at Freedman's Village as a counselor and teacher.

Truth taught courage and urged residents to stand up to nearby white landowners who had taken to raiding the village to kidnap children for slave labor. Freedman's Village parents who had reported the kidnappings earlier had been thrown in jail. But when authorities came to jail Truth for encouraging parents to keep complaining, she swore to "make this nation rock like a cradle" if they tried to silence her. They backed down, and the raids soon ended.

Life was difficult. Virginia residents resented the villagers, and threats were made against their lives. Eventually, the village site, with a spectacular view of the nation's capital and the Potomac River, became more and more desirable for development. Despite impassioned protests from the freed slaves, the federal government paid the residents $75,000 for the buildings and property, and tore down the town in 1900.

"Unfortunately our government didn't see the historic value of some of those things," Sherlock said. Saving the city would have been a "gift to the American people to remember the struggles which seem like was a long time ago, but 150 years is not that long ago," Sherlock said.

Several former villagers later held prominent positions around the former town's site. William Syphax was elected to the Virginia General Assembly. When Blacksmith William A. Rowe, left Freedman's Village, he became the first black policeman in Arlington County, Va., and later held other county posts.

Arlington National Cemetery holds little to tell people that Freedman's Village ever existed. There's a model of the town inside Arlington House, Lee's former home, but no markers or plaques on the town's site. The only trace of Freedman's Village left on the grounds are the lonely graves in Section 27 near the Iwo Jima Memorial.

Walking among the gravestones, you can see the word "citizen" on some, and "civilian" on others — a recent addition. Originally, Freedman's Village residents were buried with the word contraband on their gravestones.

"As time went on and the headstones started to deteriorate and they were being replaced, the historian saw fit to give them the honor they were due and affirmed their status as civilians." More people should know about the struggles of the villagers, we hope people will "continue to tell their stories, to bring their stories to light, in part really to give them back their dignity that the institution of slavery robbed from them but also to let the current generation know the sacrifices they made and the triumphs they had over extremely adverse circumstances," Parks said. (James Parks great grandfather lived in Freedman's Village).

Sources: Oshkosh Public Museum, Associated Press, Jesse J Holland (Apr. 2010)

Charter buses roll up to Arlington National Cemetery every day, depositing tourists who scramble uphill to see the eternal flame on President John F. Kennedy's grave. People stream in all directions, toward the Tomb of the Unknowns or to remember at tombstones of loved ones lost to war. Few, however, head downhill to a quiet corner near the Iwo Jima Memorial.

There are no memorials to ancient battles, no ornate headstones honoring long-dead dignitaries. There are only rows of small unassuming white tombstones, many engraved with names like George, Toby and Rose. They are the only visible reminders that part of the nation's most storied burial ground sits atop what used to be a thriving black town — "Freedman's Village," built on land confiscated from Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee. There's nothing there now to tell visitors that formerly enslaved men, women and children once lived there.

Arlington National Cemetery was established on land confiscated from Lee and his family in 1861 after the general took command of the Confederate forces. The Civil War leaders of the Union buried dead soldiers on the property in hopes that Lee would never want to return. The federal government turned some land about half a mile north of Lee's mansion into a town specifically for freed slaves, referred to as contraband, who had nowhere to go.

Freedman's Village was no ramshackle camp. At its height, more than 1,100 former slaves lived in a collection of 50 one-and-a-half story duplexes surrounding a central pond. Although the town was supposed to be temporary, the freed slaves put up churches, stores, a hospital, mess hall, a school, an "old people's home" and a laundry — to make a life for themselves. "I think it would have very much resembled a town anywhere in America today with that population. They had the same needs as anywhere, and they sustained themselves by working," said Thomas Sherlock, historian at Arlington National Cemetery.

Living in Freedman's Village wasn't free. Workers with government jobs on nearby farms or those doing construction were paid $10 a week, but half their salary was turned over to the federal government to pay for running the town. Everyone else who lived on site was charged between $1 and $3 rent.

Dignitaries from around the nation came to see — and sometimes stay — with residents. The most famous was Sojourner Truth, the fiery black abolitionist and preacher, who spent about a year at Freedman's Village as a counselor and teacher.

Truth taught courage and urged residents to stand up to nearby white landowners who had taken to raiding the village to kidnap children for slave labor. Freedman's Village parents who had reported the kidnappings earlier had been thrown in jail. But when authorities came to jail Truth for encouraging parents to keep complaining, she swore to "make this nation rock like a cradle" if they tried to silence her. They backed down, and the raids soon ended.

Life was difficult. Virginia residents resented the villagers, and threats were made against their lives. Eventually, the village site, with a spectacular view of the nation's capital and the Potomac River, became more and more desirable for development. Despite impassioned protests from the freed slaves, the federal government paid the residents $75,000 for the buildings and property, and tore down the town in 1900.

"Unfortunately our government didn't see the historic value of some of those things," Sherlock said. Saving the city would have been a "gift to the American people to remember the struggles which seem like was a long time ago, but 150 years is not that long ago," Sherlock said.

Several former villagers later held prominent positions around the former town's site. William Syphax was elected to the Virginia General Assembly. When Blacksmith William A. Rowe, left Freedman's Village, he became the first black policeman in Arlington County, Va., and later held other county posts.

Arlington National Cemetery holds little to tell people that Freedman's Village ever existed. There's a model of the town inside Arlington House, Lee's former home, but no markers or plaques on the town's site. The only trace of Freedman's Village left on the grounds are the lonely graves in Section 27 near the Iwo Jima Memorial.

Walking among the gravestones, you can see the word "citizen" on some, and "civilian" on others — a recent addition. Originally, Freedman's Village residents were buried with the word contraband on their gravestones.

"As time went on and the headstones started to deteriorate and they were being replaced, the historian saw fit to give them the honor they were due and affirmed their status as civilians." More people should know about the struggles of the villagers, we hope people will "continue to tell their stories, to bring their stories to light, in part really to give them back their dignity that the institution of slavery robbed from them but also to let the current generation know the sacrifices they made and the triumphs they had over extremely adverse circumstances," Parks said. (James Parks great grandfather lived in Freedman's Village).

Sources: Oshkosh Public Museum, Associated Press, Jesse J Holland (Apr. 2010)

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter