Lt. Colonel Allen Allensworth

24th Infantry Regiment Korea

Victor R Daly

Buffalo Soldiers and a President

Corporal Isaiah Mays

Unknown Soldier

Charles Edward Minor

Retired Navy

James Caldwell

William H Clark, Sr.

Peter D. Thomas

John Pinkey

New York's Finest: Samuel Battle

Willis Ward: University of Michigan Football Team

The Champ: Jack Johnson

Curt Flood

Marshall W. 'Major' Taylor

Herbert 'Rap' Dixon

Columbus Johnson

First to Die

Anthony Crawford

Walter L. 'Duck' Majors

Black Cats Group

Howard Family

A Lesson in American History

Generations

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine and her Fans(atics)

Billie's Future Poppa

Littlest Majorette

Phillis Wheatley Branch of the YWCA

Plump Cheeked Cherubs

The Barnes Girls

The Cole Kids

Siblings

LaVern Baker

Johnson and Dean

Zaidee Jackson

The Sport of the Gods

Mademoiselle Desseria Plato

Evelyn Preer

Arabella Fields

Sissieretta Joyner Jones

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

79 visits

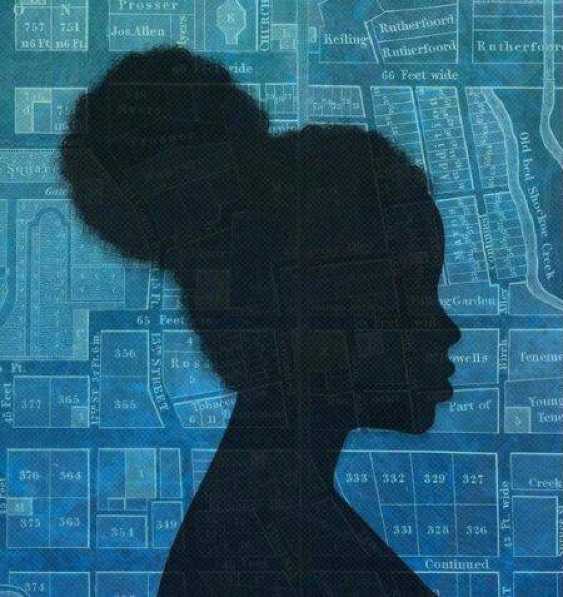

The Story of Mary Lumpkin

Around 1840, an enslaved child named Mary was sold to a man named Robert Lumpkin. He forced her to bear his children and help him run a slave jail in Richmond, Virginia. In the end, however, Mary Lumpkin turned his prison into a school for Black students.

Before and during the Civil War, slave jails were sites of confinement and torture for enslaved men, women, and children who tried to escape to free states or who were waiting to be sold. However, few were as notorious as Lumpkin’s Jail.

Mary Lumpkin witnessed the horrors that Robert put his prisoners through on a daily basis. When she inherited the jail compound upon Robert’s death, she immediately shut it down and leased it to a minister who wanted to establish a seminary for freedmen.

Today, that school is Virginia Union University. This is the story of how one enslaved woman helped turn a slave jail into one of the first historically Black colleges in the United States.

Not much is known about Mary Lumpkin’s early life, but according to Smithsonian Magazine, she was born in 1832. She was described as “fair faced” and “nearly white,” and she may have been the child of an enslaved woman and her enslaver.

Robert Lumpkin purchased Mary at some point in the late 1830s or early 1840s, when she was still a child. By the time she was 13, Mary Lumpkin had already given birth to the first of Robert’s children — and she would go on to have at least four more.

Robert, who was 27 years older than Mary, bought the slave jail in the Shockoe Bottom area of Richmond, Virginia in 1844. It became known as Lumpkin’s Jail, and it was one of the cruelest prisons in the South. Some even called it the “Devil’s Half Acre.”

As Mary Lumpkin continued to bear Robert’s children, she reportedly told him that he could treat her however he wanted as long as their kids remained free. It seems that Robert agreed. He even sent their two daughters, who were reportedly white-passing, to a finishing school in Massachusetts upon Mary’s urging.

Smithsonian Magazine reports that Charles Henry Corey, a former chaplain for the Union Army, claimed that Robert sent his daughters to school because he worried that a “financial contingency might arise when these, his own beautiful daughters, might be sold into slavery to pay his debts.”

This, of course, terrified Robert — because he knew they may be treated the same way he treated the Black prisoners who came through his jail.

There are several surviving contemporary accounts from enslaved men who were imprisoned at Lumpkin’s Jail — and some of them even mention Mary.

According to The Washington Post, a reverend named A. M. Newman recalled being sent to the jail as punishment when he was a child. He vividly remembered a “whipping room” with iron rings in the floor:

“The individual would be laid down, his hands and feet stretched out and fastened in the rings, and a great big man would stand over him and flog him.”

Newman also remembered Mary Lumpkin looking at him sadly after he was whipped. He said, “It seemed to me that she was saying ‘poor child.'”

In 1854, an enslaved man named Anthony Burns who had escaped to Boston from Virginia was captured and returned to the state because of the Fugitive Slave Act, sparking an abolitionist riot.

Despite the public outcry in the North, Burns was sent to Lumpkin’s Jail for four months as punishment. According to Encyclopedia Virginia, he was confined to a tiny room that could only be entered through a trap door. He had no bed and instead slept on “a rude bench fastened against the wall and a single, coarse blanket.”

Chains held Burns’ wrists behind his back. The irons around his legs caused painful swelling. The jailors gave Burns a fresh pail of water once a week. Once a day, he ate cornbread. Sometimes, he had a bite of spoiled meat. Unable to even relieve himself, Burns’ health dramatically declined. Even after his release, he was never the same, and he died in 1862 at the age of 28.

During the course of Burns’ imprisonment, Mary Lumpkin allegedly sneaked a Bible and a hymnal into his cell in an effort to keep his spirits up.

Although she was enslaved herself and held very little power, Mary did everything she could to help the prisoners who came through Robert’s jail. And as soon as she had the chance, she shut it all down for good.

When Robert Lumpkin died in 1866, Mary and her children were living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where they’d moved when the Civil War broke out to avoid being captured and sold into slavery.

Robert left the jail to Mary in his will, but she wanted nothing to do with it. So when she heard that an abolitionist minister named Nathaniel Colver was searching for a place to establish a seminary for formerly enslaved people, she gladly leased him the land.

Workers tore apart the jail and its cells, removing the iron bars and chains to create classrooms. On the small patch of land where enslaved people had once been tortured, Black students began receiving an education at the Richmond Theological School for Freedmen.

Charles Henry Corey declared, “The old slave pen was no longer the ‘devil’s half acre’ but ‘God’s half acre.'”

After several years, the school needed room to expand, and it moved to a different area of the city. Mary Lumpkin sold the property in 1873, and the jail was demolished in 1876. After living out the rest of her life as a free woman, Mary died in 1905 and was buried in New Richmond, Ohio.

Eventually, the Richmond Theological School for Freedmen became Virginia Union University, which remains one of the oldest HBCUs in the country to this day.

At its dedication in 1900, the university’s president spoke of Mary’s legacy: “Lumpkin’s Jail, which had been the scene of some of the most heartless and saddest incidents of slavery, now became the set of theological instruction. The rings in the floor to which slaves had been chained gave place to school desk and bench.”

And in 2022, Virginia Union University president Hakim J. Lucas said, “For Virginia Union to have a forming story rooted in Black womanness… it’s a story of its own.”

Sources: The Washington Post; Smithsonian Magazine; The Story Of Mary Lumpkin, The Formerly Enslaved Woman Who Liberated A Slave Jail And Turned It Into An HBCU, article by Genevieve Carlton/edited by Cara Johnson (Sept. 2022) for allthatsinteresting.com; Special Collections, UVA; Richmond City Council Slave Trail Commission

Before and during the Civil War, slave jails were sites of confinement and torture for enslaved men, women, and children who tried to escape to free states or who were waiting to be sold. However, few were as notorious as Lumpkin’s Jail.

Mary Lumpkin witnessed the horrors that Robert put his prisoners through on a daily basis. When she inherited the jail compound upon Robert’s death, she immediately shut it down and leased it to a minister who wanted to establish a seminary for freedmen.

Today, that school is Virginia Union University. This is the story of how one enslaved woman helped turn a slave jail into one of the first historically Black colleges in the United States.

Not much is known about Mary Lumpkin’s early life, but according to Smithsonian Magazine, she was born in 1832. She was described as “fair faced” and “nearly white,” and she may have been the child of an enslaved woman and her enslaver.

Robert Lumpkin purchased Mary at some point in the late 1830s or early 1840s, when she was still a child. By the time she was 13, Mary Lumpkin had already given birth to the first of Robert’s children — and she would go on to have at least four more.

Robert, who was 27 years older than Mary, bought the slave jail in the Shockoe Bottom area of Richmond, Virginia in 1844. It became known as Lumpkin’s Jail, and it was one of the cruelest prisons in the South. Some even called it the “Devil’s Half Acre.”

As Mary Lumpkin continued to bear Robert’s children, she reportedly told him that he could treat her however he wanted as long as their kids remained free. It seems that Robert agreed. He even sent their two daughters, who were reportedly white-passing, to a finishing school in Massachusetts upon Mary’s urging.

Smithsonian Magazine reports that Charles Henry Corey, a former chaplain for the Union Army, claimed that Robert sent his daughters to school because he worried that a “financial contingency might arise when these, his own beautiful daughters, might be sold into slavery to pay his debts.”

This, of course, terrified Robert — because he knew they may be treated the same way he treated the Black prisoners who came through his jail.

There are several surviving contemporary accounts from enslaved men who were imprisoned at Lumpkin’s Jail — and some of them even mention Mary.

According to The Washington Post, a reverend named A. M. Newman recalled being sent to the jail as punishment when he was a child. He vividly remembered a “whipping room” with iron rings in the floor:

“The individual would be laid down, his hands and feet stretched out and fastened in the rings, and a great big man would stand over him and flog him.”

Newman also remembered Mary Lumpkin looking at him sadly after he was whipped. He said, “It seemed to me that she was saying ‘poor child.'”

In 1854, an enslaved man named Anthony Burns who had escaped to Boston from Virginia was captured and returned to the state because of the Fugitive Slave Act, sparking an abolitionist riot.

Despite the public outcry in the North, Burns was sent to Lumpkin’s Jail for four months as punishment. According to Encyclopedia Virginia, he was confined to a tiny room that could only be entered through a trap door. He had no bed and instead slept on “a rude bench fastened against the wall and a single, coarse blanket.”

Chains held Burns’ wrists behind his back. The irons around his legs caused painful swelling. The jailors gave Burns a fresh pail of water once a week. Once a day, he ate cornbread. Sometimes, he had a bite of spoiled meat. Unable to even relieve himself, Burns’ health dramatically declined. Even after his release, he was never the same, and he died in 1862 at the age of 28.

During the course of Burns’ imprisonment, Mary Lumpkin allegedly sneaked a Bible and a hymnal into his cell in an effort to keep his spirits up.

Although she was enslaved herself and held very little power, Mary did everything she could to help the prisoners who came through Robert’s jail. And as soon as she had the chance, she shut it all down for good.

When Robert Lumpkin died in 1866, Mary and her children were living in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where they’d moved when the Civil War broke out to avoid being captured and sold into slavery.

Robert left the jail to Mary in his will, but she wanted nothing to do with it. So when she heard that an abolitionist minister named Nathaniel Colver was searching for a place to establish a seminary for formerly enslaved people, she gladly leased him the land.

Workers tore apart the jail and its cells, removing the iron bars and chains to create classrooms. On the small patch of land where enslaved people had once been tortured, Black students began receiving an education at the Richmond Theological School for Freedmen.

Charles Henry Corey declared, “The old slave pen was no longer the ‘devil’s half acre’ but ‘God’s half acre.'”

After several years, the school needed room to expand, and it moved to a different area of the city. Mary Lumpkin sold the property in 1873, and the jail was demolished in 1876. After living out the rest of her life as a free woman, Mary died in 1905 and was buried in New Richmond, Ohio.

Eventually, the Richmond Theological School for Freedmen became Virginia Union University, which remains one of the oldest HBCUs in the country to this day.

At its dedication in 1900, the university’s president spoke of Mary’s legacy: “Lumpkin’s Jail, which had been the scene of some of the most heartless and saddest incidents of slavery, now became the set of theological instruction. The rings in the floor to which slaves had been chained gave place to school desk and bench.”

And in 2022, Virginia Union University president Hakim J. Lucas said, “For Virginia Union to have a forming story rooted in Black womanness… it’s a story of its own.”

Sources: The Washington Post; Smithsonian Magazine; The Story Of Mary Lumpkin, The Formerly Enslaved Woman Who Liberated A Slave Jail And Turned It Into An HBCU, article by Genevieve Carlton/edited by Cara Johnson (Sept. 2022) for allthatsinteresting.com; Special Collections, UVA; Richmond City Council Slave Trail Commission

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter