The Plummer Family

Allen Family

Family Robbins

Sydney and Marshall

The Honeymooners

Green Family

The Connollys

Slavery By Another Name

Harvest Moon Dance

Queen Bess and the Black Eagle

Colorfornia: The California Magazine

Negro Romance

Watts Riots

Lindy Hoppers

4 Sets of Smiles

Pepper Picker in Louisiana

Rodeo Cowboy

The Almighty Fro

Catherine Delany

Mother's Club

George W Forbes

Altanta's First Black Photographer

Early Black Daugurreotypist

Double Image: Morgan and Marvin Smith

Family of Six

Wilbur and Ardie Halyard

Higdon Family

The Ricks

Mossell Family

31627519565 2c05d94d5e b

Photog and his Sons

The Taylor Family

The Batteys

A Louisiana Family

Dad's Girls

Goodridge Family

Saying Good-bye

The Walkers

Virginia and Joshua: A Love Story

The Harpers: Frances Ellen Watkins and Mary

Pioneers of Flight: Willa Brown and Cornelius Coff…

William Henry and Nannie Brewer Johnson

Mr. and Mrs. Keepson

Frederick and Little Annie

Joe Louis and Co.

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

48 visits

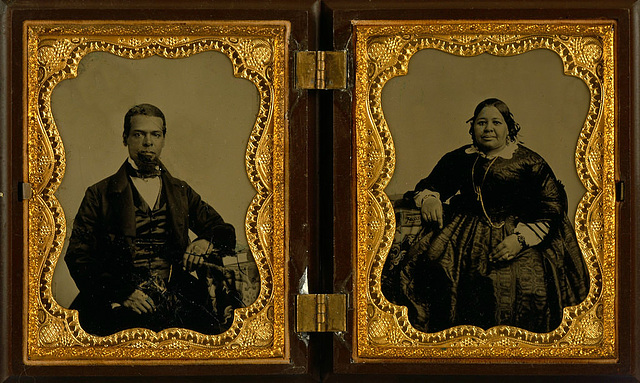

The Mighty Lyons

Ambrotype of Albro Lyons, Sr. and his wife Mary Joseph Marshall Lyons, circa 1860. Photographs and Prints Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Albro and Mary Lyons lived with their children – Therese, Maritcha, Pauline, and Albro, Jr., in the Seaman’s Home on Vandewater Street. Albro Lyons owned the Home, which he ran as a boardinghouse for black seamen. It was also a station on the Underground Railroad, the comings and goings of the guests covering the comings and goings of fugitive slaves. Albro Lyons was well known in the city and prominent among black activists.

Mary and Albro Lyons and two of their children were at home on the first day of the 1863 Draft Riot in New York City and could hear the mayhem in the streets outside. Maritcha Lyons, fifteen at the time, later wrote about what happened. Late on Monday, “a rabble attacked our house, breaking windowpanes, smashing shutters, and partially demolishing the main front door” before being distracted. Maritcha’s parents picked up the stones that had been thrown and used them to barricade the exposed front door. They kept watch all night, in “darkness, indignation, uncertainty, and dread.” At one point they heard someone yell outside. Albro Lyons stood in his doorway and fired a shot into the crowd; there was no attack.

Before dawn, the two Lyons children were shepherded to safety, and the parents remained to guard their house and property. Early in the morning, they heard footsteps and a voice: “Don’t shoot, Al. It’s only me.” Officer Kelly from the local precinct had heard of the attack on the Seaman’s Home and came by to make sure that the Lyons family was all right. Overcome by the violence and his helplessness, Kelly sat on the Lyons’s steps and “sobbed like a child.”

A few hours later, the mob arrived again, more determined. This time Albro Lyons ran to the police station – chased the entire way – and Mary raced to the home of a German neighbor, who had already loosened boards in his fence in case she needed to escape. He was later assaulted for helping his black neighbor. With the Lyons house empty, the rioters entered, destroyed everything they could find, and set a fire in an upstairs room. They stopped when the police arrived. Mary and Albro spent that night in the precinct with many other black New Yorkers. After midnight, the police helped them cross the East River to Williamsburg. Albro and Mary collected their children and fled the city.

Finally the Union army arrived and restored order, but over 100 blacks had been killed in brutal ways. Women, children, men – no black person was safe from the mob’s wrath. In the uneasy calm that followed, Albro Lyons wrote an inventory more than 12 pages long, listing the household items he had lost: mirrors, chairs, children’s clothes, china vases. It amounted to over $2000, a sign of the Lyons family’s prosperity when many workers earned one dollar a day. The family was partly reimbursed by the Committee of Merchants, which had organized a relief effort for the black victims of the violence. They remained in New York for about a year after the riots, but eventually they joined the great migration of blacks who could no longer bear the stress of living in New York City. The Lyons family resettled in Providence, Rhode Island, where their daughter Maritcha finished school. As an adult, she returned to New York to become a teacher and assistant principal at Public School 83, Brooklyn.

Sources: Tonya Bolden, Maritcha: A Nineteenth-Century American Girl (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2005); Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999);

Albro and Mary Lyons lived with their children – Therese, Maritcha, Pauline, and Albro, Jr., in the Seaman’s Home on Vandewater Street. Albro Lyons owned the Home, which he ran as a boardinghouse for black seamen. It was also a station on the Underground Railroad, the comings and goings of the guests covering the comings and goings of fugitive slaves. Albro Lyons was well known in the city and prominent among black activists.

Mary and Albro Lyons and two of their children were at home on the first day of the 1863 Draft Riot in New York City and could hear the mayhem in the streets outside. Maritcha Lyons, fifteen at the time, later wrote about what happened. Late on Monday, “a rabble attacked our house, breaking windowpanes, smashing shutters, and partially demolishing the main front door” before being distracted. Maritcha’s parents picked up the stones that had been thrown and used them to barricade the exposed front door. They kept watch all night, in “darkness, indignation, uncertainty, and dread.” At one point they heard someone yell outside. Albro Lyons stood in his doorway and fired a shot into the crowd; there was no attack.

Before dawn, the two Lyons children were shepherded to safety, and the parents remained to guard their house and property. Early in the morning, they heard footsteps and a voice: “Don’t shoot, Al. It’s only me.” Officer Kelly from the local precinct had heard of the attack on the Seaman’s Home and came by to make sure that the Lyons family was all right. Overcome by the violence and his helplessness, Kelly sat on the Lyons’s steps and “sobbed like a child.”

A few hours later, the mob arrived again, more determined. This time Albro Lyons ran to the police station – chased the entire way – and Mary raced to the home of a German neighbor, who had already loosened boards in his fence in case she needed to escape. He was later assaulted for helping his black neighbor. With the Lyons house empty, the rioters entered, destroyed everything they could find, and set a fire in an upstairs room. They stopped when the police arrived. Mary and Albro spent that night in the precinct with many other black New Yorkers. After midnight, the police helped them cross the East River to Williamsburg. Albro and Mary collected their children and fled the city.

Finally the Union army arrived and restored order, but over 100 blacks had been killed in brutal ways. Women, children, men – no black person was safe from the mob’s wrath. In the uneasy calm that followed, Albro Lyons wrote an inventory more than 12 pages long, listing the household items he had lost: mirrors, chairs, children’s clothes, china vases. It amounted to over $2000, a sign of the Lyons family’s prosperity when many workers earned one dollar a day. The family was partly reimbursed by the Committee of Merchants, which had organized a relief effort for the black victims of the violence. They remained in New York for about a year after the riots, but eventually they joined the great migration of blacks who could no longer bear the stress of living in New York City. The Lyons family resettled in Providence, Rhode Island, where their daughter Maritcha finished school. As an adult, she returned to New York to become a teacher and assistant principal at Public School 83, Brooklyn.

Sources: Tonya Bolden, Maritcha: A Nineteenth-Century American Girl (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2005); Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999);

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter