Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker: International Spy

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Joyce Bryant: The Bronze Blond Bombshell

Frankie and Billie

A Profile in Jazz: Eric Dolphy

Annisteen Allen

Hadda Brooks

Sassy Sarah

LaVern Baker

Donald Byrd

Erroll Garner

Lady Day

Three B's and a Honey

First Black Teen Idol: Sonny Til

Evelyn Dove

Lady Day

Jo Jo

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Interview with a Diva

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Jo and her Count

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

Miss Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

38 visits

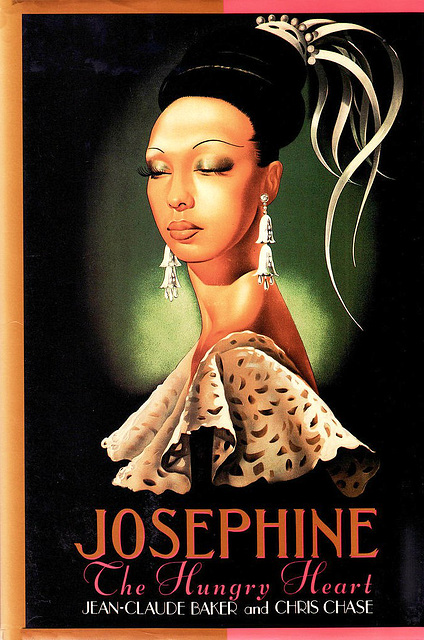

Josephine Baker: The Hungry Heart

A book I own and highly recommend for any lovers of the great Josephine Baker.

NY Times

An American From Paris

Article written by Mindy Aloff

January 30, 1994

JOSEPHINE The Hungry Heart. By Jean-Claude Baker and Chris Chase. Illustrated. 532 pp. New York: Random House. $27.50.

Josephine Baker spent the first two decades of her life wishing for fame and the next half-century dealing with it. Her wish was granted literally overnight. At the age of 19, she traveled from New York to Paris with a show called "La Revue Negre," which opened at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees on October 2, 1925. The finale of the evening was a "Charleston Cabaret," whose featured number (thrown together at the last minute) has come to be known as "La Danse de Sauvage." A big, good-looking performer named Joe Alex, wearing next to nothing, paced onto the stage with a woman slung over his back: the 5-foot-8, coffee-colored Josephine, built like a Modigliani Venus. The handful of feathers she wore did not impede anyone's appreciation of her nudity. She slid down her partner's legs and proceeded to offer up to him every soft spot of her body, in musical time. In fact, she seemed to create musical time, her movement setting the pulse, with the orchestra going along for the ride. There wasn't a dance step in sight, but "La Danse de Sauvage" created one of the great dance effects of the 20th century.

On October 3rd, Josephine Baker woke up to find herself the American in Paris, her rear end the subject of odes, her thighs the subject of universal speculation, her celebrity assured. Over the next decade -- with help from some of the most brilliant theatrical minds in the business (including George Balanchine, a devoted admirer) -- she would refine her image. Her timing would become more calculated, her costumes more sophisticated, her routines more glamorous. She would perform her eccentric dancing in an evening gown, on point. Her innate comedic talents would be chastened. Her singing voice would deepen and grow more expressive. She would enjoy worldwide renown as a beloved institution: Josephine, the Eiffel Tower of music hall revues, cabaret and film. Respectability notwithstanding, embedded in her image would always be the hot American girl whom Americans cold-shouldered and about whom 50 million Frenchmen were delighted not to be wrong.

Her life, as told in "Josephine: The Hungry Heart," is an irresistible story. It includes international intrigue during World War II (when Baker worked as a smuggler for the French Resistance from a base in North Africa) and episodes of racism in the United States, where she was the target of both whites and blacks. (As a teen-ager breaking into show business, she endured the humiliation of being barred from whites-only hotels and dining cars on trains, as well as being ridiculed by lighter-skinned black chorus girls.) Much of her offstage life after the war was taken up with the adoption and rearing of 12 orphans from around the world as an experiment in international harmony (Baker called them "the Rainbow Tribe"), with her efforts to get out of debt, and with her plans to turn her castle in southern France, Les Milandes, into a public attraction on the order of a theme park. Her ever-expanding network of illustrious friendships could serve as the subject of an independent monograph. When she felt adored she became radiant and funny, thoroughly spontaneous, bathing everyone around her in a bewitching elixir of health and crazy youth. The less innocent your own illusions about the world were, the more likely you were to respond to her charm. (Her circle included Ernest Hemingway, Jean Cocteau, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Colette, Grace Kelly and Eva Peron.) And the complete chronicle of Baker's love affairs would require several volumes. She was endowed with fantastical energy; onstage it drove her dancing, offstage it gave her a ravenous sexual appetite. By her own account, the number of her sexual partners ran into four figures. If you include the virtual affairs with her audiences -- her performances were built on the art of seduction -- the tally of liaisons gets lost in the millions.

"Josephine: The Hungry Heart" is not the first study of this modern Salome that attempts to pluck off her veils, but it is the first to do so persuasively. The success is a shared one. The biography's rhetorical fluency and narrative techniques, which briskly goad the reader through more than 500 pages clanging with the sound of famous names being dropped, are contributed by Chris Chase, who has written widely about show business and collaborated on two books with Betty Ford. The story itself, the prodigious research that buttresses it (including many new interviews) and the point of view, which ranges from professional admiration to scathing personal indictment, belong to Jean-Claude Baker, who knew Josephine Baker so well that she used to call him "the 13th of my 12 adopted children," and who in return took her surname as his own.

During the seven years before Josephine died in 1975 at the age of 68, Mr. Baker served her in a variety of ways -- as a de facto manager, an aide-de-camp, an escort, a nurse. At first he idolized her, but over the years she scorched his pride and lacerated his feelings, and he began to look at her, up close, with detachment. After her death, his cooling detachment congealed into an obsession. "I've never been her lover," he says in his introduction. "I've never even been her fan. . . . I loved her, hated her and wanted desperately to understand her." As the book makes clear, for Mr. Baker to understand her was to understand himself. This double mission is so powerful for him that he occasionally stops speaking to the reader and addresses Josephine directly. The effect sometimes is claustrophobic -- one obsessive interrogating another in a closed room -- but the intimacy and the insider knowledge are also perversely fascinating. Here is Josephine Baker stripped of glamour and defenses, Josephine Baker without apology, in places Josephine Baker presented without pity.

If Mr. Baker's view of himself were not as complex as it is, the book would simply be hateful. Yet it is neither merely hateful nor simple. Josephine Baker emerges as one of the most paradoxical figures in 20th-century entertainment, a victim of her own luck and talent who ultimately victimized everyone who loved her, an embodiment of untethered will and autonomy who could not free herself within. Her legend is dismantled with a vengeance, yet in the process her humanity is affirmed.

In the end, Mr. Baker evinces compassion for his adopted mother, but he makes her twist in the wind first. His torch of truth lays bare her lies, her hypocrisy, her self-cocooning ambition, her hypodermic "youth" injections, her bigamies, her bald scalp under the luxuriant wigs, and the unresolved resentments harbored against her by those who knew her best. In the glare, we often lose sight of the poor unhappy black child who reinvented herself as a legend in her own lifetime -- the Josephine Baker of previous biographies and memoirs. Instead, we are given a woman who on some levels never grew up in a society that lauded her for dramatizing the very instability, inconstancy and willfulness that we laugh about in children and, when we see them in adults, call madness. Indeed, this irony is one of Mr. Baker's major points about Josephine Baker. The stage became her interior life, and her private life functioned for her as a stage. Sometimes she had no comprehension that partitions were breaking down; sometimes she knew and paid no attention; sometimes she knew and wanted to change but felt helpless, and guiltily let the dam burst, then hoped to make everything right again with comforting lies.

Mr. Baker will not be her accomplice. He ridicules even Baker's subtlest attempts to manipulate human relationships ("poured on the snake oil" is how he describes one of them), and his sense of her profound injustice toward him fueled his slow-burning patience, which led him to track down the evidence that will condemn her. He has uncovered many new facts. He demolishes Baker's claim to have witnessed the 1917 massacre of blacks by rioting whites in her native East St. Louis, Ill., and he proves that she never divorced her second husband, Billy Baker. He casts doubt that she ever acquired French citizenship, as "she would claim -- and flaunt." He argues convincingly that Baker's blowup in 1951 with Walter Winchell over what she called racist treatment at Manhattan's Stork Club (she charged Winchell with passively permitting her mistreatment by the club's owner, Sherman Billingsley) was sparked not by racism but by Baker's own arrogance. And he conjectures from firsthand knowledge that Baker's disorganized management of Les Milandes was directly responsible for her loss of the property, and that she exploited the Rainbow Tribe by charging the public a fee to gaze at the children from behind a window.

Some of Mr. Baker's research illuminates her stage work: his account of specific theatrical techniques that she picked up from fellow black vaudevillians during her adolescence is completely new. Yet he also attacks her for lack of discipline, suggesting that she could be lazy about learning song sequences and lines and thereby compromised her talent.

There is one thing about Josephine Baker that Mr. Baker never fails to admire, however: her guts -- as in this wartime anecdote, for which he awards her a rare halo:

"All went well until she clashed in a Cairo nightclub with Egypt's King Farouk. The director of the club came to the table where Josephine sat with her date, an Englishman, and said His Majesty would like her to sing. Josephine declined. Farouk sent another minion: 'It is an order, you do not refuse a king.'

"Josephine got up to dance with the Englishman. The king ordered the orchestra to stop playing. The music was finished, Josephine was not. 'His Majesty should have understood,' she said, sweetly, 'that if I broke the rules, it was only to be happy.'

"A few days later, in the name of Franco-Egyptian friendship, she participated in a royal evening. Still, she had faced down a king. He was fat, but she was tough."

The vignette is meant to be instructive as well as amusing. Below this Josephine, the biographers do not go. The irreducible core of the star's personality is a mystery that cannot be cracked. One catches glimpses of it throughout the book: the young girl who walked on window ledges just for the hell of it, the chorine who jumped out of line and stole the show by clowning independently, the hedonist who knew that her unadorned body was delectable and served it up shamelessly to embarrassed deliverymen to prove the point, the ailing sexagenarian who was determined to make one more comeback when everyone warned her not to. (She fell into her final coma in Paris after two performances, her glowing press notices strewn across her bed.) This Josephine Baker, the icon of the id, does not explain the witty stylist whose legs and hands remained graceful into her 69th year or the woman whose possessions included Franz Liszt's piano, but she does light up the little child who staged amateur theatricals in the basements of East St. Louis. And she seems exactly the Josephine Baker that Jean-Claude Baker's own compulsion to write this book deserves. "Josephine: The Hungry Heart" tells you everything you never wanted to know about a femme fatale whose grand illusion, in and out of the spotlight, was the promise of naked intimacy. The authors take you deeply inside her -- with an exploding bullet -- and she rises up as interesting as ever. For all parties concerned, the confrontation is a killer achievement.

In the streets she was besieged for autographs. . . . No question but she had an air. A reporter described . . . Josephine's making an entrance in a "cherry-colored dress, small hat pulled low over her forehead, ermine-trimmed coat. 'Paris is marvelous,' she gushes. 'And your dressmakers are divine.' " (In her memoirs, she offered one final thought on fashion: "Love dresses you better than all the dressmakers.")

Ten glorious weeks "La Revue Negre" played at the Music Hall of the Champs-Elysees. Booked for a fortnight, it was extended and extended. Early in November, Josephine and company were still dancing there while the great Pavlova waited impatiently for the theater she had been promised.

On Nov. 7, under the auspices of the President of the Republic, Gaston Doumergue, there was a dinner to mark the closing of the exposition. Pavlova danced (with M. Veron) during the appetizer, Josephine (with Honey Boy) during the main course. As though the great Russian were nothing but a warm-up act for the headliner.

Obsession, exorcism, penance, retribution -- all these seethe between the covers of "Josephine," the biography that resulted from Jean-Claude Baker's 18-year search for the truth behind the legend of Josephine Baker.

"She has enslaved me, absolutely; I don't want to revolt against it," he said during an interview in his Upper East Side apartment, where Josephine Baker is a palpable presence. Posters, in English, German or French, announce long-ago performances; a lamp in the shape of a banana-belted Josephine glows on a table; hundreds of files contain research for the biography, like the 2,000 interviews Mr. Baker conducted in the United States, France, Morocco and Japan, the replies to the 3,000 letters he sent in quest of information and hundreds of yellowing newspaper clippings.

Mr. Baker started work when books about Josephine began to appear soon after her death in 1975. "When Josephine passed away and I saw the first book, then the second book, then the third book, what I could sense about her was not there or wrongly interpreted," he said. "The more I read, the more I was upset."

More important, he needed to make sense of the maelstrom of emotions he felt about the woman who emotionally sheltered him when he was a lonely, rejected 14-year-old bellhop, who served her in a Paris hotel in 1958. "She seemed to be the first person who cared about me," said Mr. Baker, an illegitimate child who had fled the scorn of a village in Burgundy. "It was like the Virgin Mary talking to me."

Mr. Baker was never adopted by Josephine Baker; he is not one of the "Rainbow Tribe," the multiethnic brood of 12 she gathered after World War II. (He took her name when he came to the United States in 1973.) However, she came to call him "the 13th of my 12 adopted children" when he became her general factotum during the series of comeback performances that marked the final seven years of her life. Mr. Baker believes that their two scarred childhoods gave them a special intimacy. "Josephine always felt, rightly or wrongly, that the world did not love her," he said. "I could always sense her sadness."

"To be with her was magic, you would forgive everything," he said, even as he described Josephine as manipulative and ruthless, a self-centered superstar who unceremoniously dropped those for whom she no longer had any use -- including, ultimately, Jean-Claude Baker.

"She was a prisoner of her own creation," he said. "She was a prisoner of Josephine Baker -- a willing prisoner." Michael Anderson

NY Times

An American From Paris

Article written by Mindy Aloff

January 30, 1994

JOSEPHINE The Hungry Heart. By Jean-Claude Baker and Chris Chase. Illustrated. 532 pp. New York: Random House. $27.50.

Josephine Baker spent the first two decades of her life wishing for fame and the next half-century dealing with it. Her wish was granted literally overnight. At the age of 19, she traveled from New York to Paris with a show called "La Revue Negre," which opened at the Theatre des Champs-Elysees on October 2, 1925. The finale of the evening was a "Charleston Cabaret," whose featured number (thrown together at the last minute) has come to be known as "La Danse de Sauvage." A big, good-looking performer named Joe Alex, wearing next to nothing, paced onto the stage with a woman slung over his back: the 5-foot-8, coffee-colored Josephine, built like a Modigliani Venus. The handful of feathers she wore did not impede anyone's appreciation of her nudity. She slid down her partner's legs and proceeded to offer up to him every soft spot of her body, in musical time. In fact, she seemed to create musical time, her movement setting the pulse, with the orchestra going along for the ride. There wasn't a dance step in sight, but "La Danse de Sauvage" created one of the great dance effects of the 20th century.

On October 3rd, Josephine Baker woke up to find herself the American in Paris, her rear end the subject of odes, her thighs the subject of universal speculation, her celebrity assured. Over the next decade -- with help from some of the most brilliant theatrical minds in the business (including George Balanchine, a devoted admirer) -- she would refine her image. Her timing would become more calculated, her costumes more sophisticated, her routines more glamorous. She would perform her eccentric dancing in an evening gown, on point. Her innate comedic talents would be chastened. Her singing voice would deepen and grow more expressive. She would enjoy worldwide renown as a beloved institution: Josephine, the Eiffel Tower of music hall revues, cabaret and film. Respectability notwithstanding, embedded in her image would always be the hot American girl whom Americans cold-shouldered and about whom 50 million Frenchmen were delighted not to be wrong.

Her life, as told in "Josephine: The Hungry Heart," is an irresistible story. It includes international intrigue during World War II (when Baker worked as a smuggler for the French Resistance from a base in North Africa) and episodes of racism in the United States, where she was the target of both whites and blacks. (As a teen-ager breaking into show business, she endured the humiliation of being barred from whites-only hotels and dining cars on trains, as well as being ridiculed by lighter-skinned black chorus girls.) Much of her offstage life after the war was taken up with the adoption and rearing of 12 orphans from around the world as an experiment in international harmony (Baker called them "the Rainbow Tribe"), with her efforts to get out of debt, and with her plans to turn her castle in southern France, Les Milandes, into a public attraction on the order of a theme park. Her ever-expanding network of illustrious friendships could serve as the subject of an independent monograph. When she felt adored she became radiant and funny, thoroughly spontaneous, bathing everyone around her in a bewitching elixir of health and crazy youth. The less innocent your own illusions about the world were, the more likely you were to respond to her charm. (Her circle included Ernest Hemingway, Jean Cocteau, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Colette, Grace Kelly and Eva Peron.) And the complete chronicle of Baker's love affairs would require several volumes. She was endowed with fantastical energy; onstage it drove her dancing, offstage it gave her a ravenous sexual appetite. By her own account, the number of her sexual partners ran into four figures. If you include the virtual affairs with her audiences -- her performances were built on the art of seduction -- the tally of liaisons gets lost in the millions.

"Josephine: The Hungry Heart" is not the first study of this modern Salome that attempts to pluck off her veils, but it is the first to do so persuasively. The success is a shared one. The biography's rhetorical fluency and narrative techniques, which briskly goad the reader through more than 500 pages clanging with the sound of famous names being dropped, are contributed by Chris Chase, who has written widely about show business and collaborated on two books with Betty Ford. The story itself, the prodigious research that buttresses it (including many new interviews) and the point of view, which ranges from professional admiration to scathing personal indictment, belong to Jean-Claude Baker, who knew Josephine Baker so well that she used to call him "the 13th of my 12 adopted children," and who in return took her surname as his own.

During the seven years before Josephine died in 1975 at the age of 68, Mr. Baker served her in a variety of ways -- as a de facto manager, an aide-de-camp, an escort, a nurse. At first he idolized her, but over the years she scorched his pride and lacerated his feelings, and he began to look at her, up close, with detachment. After her death, his cooling detachment congealed into an obsession. "I've never been her lover," he says in his introduction. "I've never even been her fan. . . . I loved her, hated her and wanted desperately to understand her." As the book makes clear, for Mr. Baker to understand her was to understand himself. This double mission is so powerful for him that he occasionally stops speaking to the reader and addresses Josephine directly. The effect sometimes is claustrophobic -- one obsessive interrogating another in a closed room -- but the intimacy and the insider knowledge are also perversely fascinating. Here is Josephine Baker stripped of glamour and defenses, Josephine Baker without apology, in places Josephine Baker presented without pity.

If Mr. Baker's view of himself were not as complex as it is, the book would simply be hateful. Yet it is neither merely hateful nor simple. Josephine Baker emerges as one of the most paradoxical figures in 20th-century entertainment, a victim of her own luck and talent who ultimately victimized everyone who loved her, an embodiment of untethered will and autonomy who could not free herself within. Her legend is dismantled with a vengeance, yet in the process her humanity is affirmed.

In the end, Mr. Baker evinces compassion for his adopted mother, but he makes her twist in the wind first. His torch of truth lays bare her lies, her hypocrisy, her self-cocooning ambition, her hypodermic "youth" injections, her bigamies, her bald scalp under the luxuriant wigs, and the unresolved resentments harbored against her by those who knew her best. In the glare, we often lose sight of the poor unhappy black child who reinvented herself as a legend in her own lifetime -- the Josephine Baker of previous biographies and memoirs. Instead, we are given a woman who on some levels never grew up in a society that lauded her for dramatizing the very instability, inconstancy and willfulness that we laugh about in children and, when we see them in adults, call madness. Indeed, this irony is one of Mr. Baker's major points about Josephine Baker. The stage became her interior life, and her private life functioned for her as a stage. Sometimes she had no comprehension that partitions were breaking down; sometimes she knew and paid no attention; sometimes she knew and wanted to change but felt helpless, and guiltily let the dam burst, then hoped to make everything right again with comforting lies.

Mr. Baker will not be her accomplice. He ridicules even Baker's subtlest attempts to manipulate human relationships ("poured on the snake oil" is how he describes one of them), and his sense of her profound injustice toward him fueled his slow-burning patience, which led him to track down the evidence that will condemn her. He has uncovered many new facts. He demolishes Baker's claim to have witnessed the 1917 massacre of blacks by rioting whites in her native East St. Louis, Ill., and he proves that she never divorced her second husband, Billy Baker. He casts doubt that she ever acquired French citizenship, as "she would claim -- and flaunt." He argues convincingly that Baker's blowup in 1951 with Walter Winchell over what she called racist treatment at Manhattan's Stork Club (she charged Winchell with passively permitting her mistreatment by the club's owner, Sherman Billingsley) was sparked not by racism but by Baker's own arrogance. And he conjectures from firsthand knowledge that Baker's disorganized management of Les Milandes was directly responsible for her loss of the property, and that she exploited the Rainbow Tribe by charging the public a fee to gaze at the children from behind a window.

Some of Mr. Baker's research illuminates her stage work: his account of specific theatrical techniques that she picked up from fellow black vaudevillians during her adolescence is completely new. Yet he also attacks her for lack of discipline, suggesting that she could be lazy about learning song sequences and lines and thereby compromised her talent.

There is one thing about Josephine Baker that Mr. Baker never fails to admire, however: her guts -- as in this wartime anecdote, for which he awards her a rare halo:

"All went well until she clashed in a Cairo nightclub with Egypt's King Farouk. The director of the club came to the table where Josephine sat with her date, an Englishman, and said His Majesty would like her to sing. Josephine declined. Farouk sent another minion: 'It is an order, you do not refuse a king.'

"Josephine got up to dance with the Englishman. The king ordered the orchestra to stop playing. The music was finished, Josephine was not. 'His Majesty should have understood,' she said, sweetly, 'that if I broke the rules, it was only to be happy.'

"A few days later, in the name of Franco-Egyptian friendship, she participated in a royal evening. Still, she had faced down a king. He was fat, but she was tough."

The vignette is meant to be instructive as well as amusing. Below this Josephine, the biographers do not go. The irreducible core of the star's personality is a mystery that cannot be cracked. One catches glimpses of it throughout the book: the young girl who walked on window ledges just for the hell of it, the chorine who jumped out of line and stole the show by clowning independently, the hedonist who knew that her unadorned body was delectable and served it up shamelessly to embarrassed deliverymen to prove the point, the ailing sexagenarian who was determined to make one more comeback when everyone warned her not to. (She fell into her final coma in Paris after two performances, her glowing press notices strewn across her bed.) This Josephine Baker, the icon of the id, does not explain the witty stylist whose legs and hands remained graceful into her 69th year or the woman whose possessions included Franz Liszt's piano, but she does light up the little child who staged amateur theatricals in the basements of East St. Louis. And she seems exactly the Josephine Baker that Jean-Claude Baker's own compulsion to write this book deserves. "Josephine: The Hungry Heart" tells you everything you never wanted to know about a femme fatale whose grand illusion, in and out of the spotlight, was the promise of naked intimacy. The authors take you deeply inside her -- with an exploding bullet -- and she rises up as interesting as ever. For all parties concerned, the confrontation is a killer achievement.

In the streets she was besieged for autographs. . . . No question but she had an air. A reporter described . . . Josephine's making an entrance in a "cherry-colored dress, small hat pulled low over her forehead, ermine-trimmed coat. 'Paris is marvelous,' she gushes. 'And your dressmakers are divine.' " (In her memoirs, she offered one final thought on fashion: "Love dresses you better than all the dressmakers.")

Ten glorious weeks "La Revue Negre" played at the Music Hall of the Champs-Elysees. Booked for a fortnight, it was extended and extended. Early in November, Josephine and company were still dancing there while the great Pavlova waited impatiently for the theater she had been promised.

On Nov. 7, under the auspices of the President of the Republic, Gaston Doumergue, there was a dinner to mark the closing of the exposition. Pavlova danced (with M. Veron) during the appetizer, Josephine (with Honey Boy) during the main course. As though the great Russian were nothing but a warm-up act for the headliner.

Obsession, exorcism, penance, retribution -- all these seethe between the covers of "Josephine," the biography that resulted from Jean-Claude Baker's 18-year search for the truth behind the legend of Josephine Baker.

"She has enslaved me, absolutely; I don't want to revolt against it," he said during an interview in his Upper East Side apartment, where Josephine Baker is a palpable presence. Posters, in English, German or French, announce long-ago performances; a lamp in the shape of a banana-belted Josephine glows on a table; hundreds of files contain research for the biography, like the 2,000 interviews Mr. Baker conducted in the United States, France, Morocco and Japan, the replies to the 3,000 letters he sent in quest of information and hundreds of yellowing newspaper clippings.

Mr. Baker started work when books about Josephine began to appear soon after her death in 1975. "When Josephine passed away and I saw the first book, then the second book, then the third book, what I could sense about her was not there or wrongly interpreted," he said. "The more I read, the more I was upset."

More important, he needed to make sense of the maelstrom of emotions he felt about the woman who emotionally sheltered him when he was a lonely, rejected 14-year-old bellhop, who served her in a Paris hotel in 1958. "She seemed to be the first person who cared about me," said Mr. Baker, an illegitimate child who had fled the scorn of a village in Burgundy. "It was like the Virgin Mary talking to me."

Mr. Baker was never adopted by Josephine Baker; he is not one of the "Rainbow Tribe," the multiethnic brood of 12 she gathered after World War II. (He took her name when he came to the United States in 1973.) However, she came to call him "the 13th of my 12 adopted children" when he became her general factotum during the series of comeback performances that marked the final seven years of her life. Mr. Baker believes that their two scarred childhoods gave them a special intimacy. "Josephine always felt, rightly or wrongly, that the world did not love her," he said. "I could always sense her sadness."

"To be with her was magic, you would forgive everything," he said, even as he described Josephine as manipulative and ruthless, a self-centered superstar who unceremoniously dropped those for whom she no longer had any use -- including, ultimately, Jean-Claude Baker.

"She was a prisoner of her own creation," he said. "She was a prisoner of Josephine Baker -- a willing prisoner." Michael Anderson

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter