Mary Sampson Patterson Leary Langston

Pete and Repeat

Lucille Bishop Smith

Miss Pope: The Rosa Parks of DC

Mary Church Terrell

Harriet Russell

Kitty Dotson House Pollard

Leah Pitts

Louise DeMortie

Katherine 'Kittie' Knox

Elizabeth “Lizzie” Austin Taylor

Althea Gibson

Mabel Fairbanks

Mamie Cunningham

Daniel Freeman: DC's 1st Black Photographer

Robert Blair

Wells and Wells

Madame Marie Selika

Louisa Melvin Delos Mars

Belle Davis

The Cake Walkers

Madam Desseria Plato

The Black Swan: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield

Bettiola Heloise Fortson

Elizabeth B. Slaughter

Mrs. Molyneaux Hewlett Douglass

Elizabeth A. Gloucester: The Wealthiest Black Woma…

Their Gold Was Not Tarnished: Loved Ones of the F…

1st Black Female Aviatrix: Bessie Coleman

Marie A. D. Madre Marshall

Forgotten No More: Annie Malone

Annie Mae Hunt

Addie Rysinger

Julia P Hughes

Martha Bailey Briggs

Alethia Browning Tanner

Lady Bicyclists

Elizabeth Jennie Adams Carter

Caroline Still Anderson

Dr. Catharine Deaver Lealtad

William Henry Hunt and Ida Alexander Gibbs

Harriet Gibbs Marshall

Mary Beatrice Davidson Kenner

Charlotte Louise Forten Grimké

Elise Forrest Harleston

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

37 visits

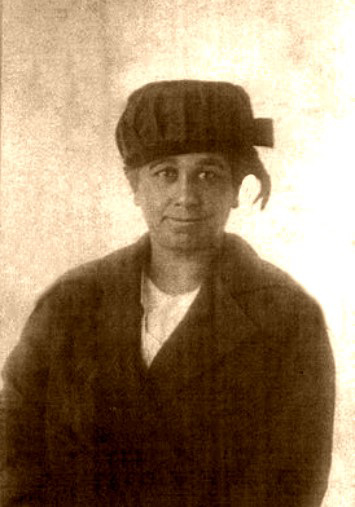

Officer Bertha Whedbee

She was a former kindergarten teacher who joined the Louisville Police Department after local officers mistreated her son. She petitioned the department to be appointed as a police officer and was allowed ---- but only to work with other blacks in the community.

Officer Bertha Whedbee joined Louisiana Metro Police Department in 1922, decades before the Civil Rights movement and only two years after women got the right to vote.

Almost a century after changing the course of history for the city's police department, Louisville's first African-American policewoman is finally getting the recognition she deserves.

Sometime around 2017, now retired Louisville Police Sgt. Chuck Cooper came across mention of Officer Bertha Whedbee's story on Facebook. He found out she had become the first African-American female officer in March 1922 after having a petition signed by voters requesting she be appointed.

After some digging, Cooper and some other police officers discovered Whedbee and her husband were buried in an unmarked grave at Louisville Cemetery.

"We thought that was terrible," Cooper said. "She is one of our police family, and we take care of our family."

Along with a group of eight other officers, Cooper organized a campaign on GoFundMe, a crowdfunding website, to raise money to get a headstone for Whedbee and her husband, Ellis Whedbee, a doctor who co-founded Louisville's Red Cross Hospital and Nurse Training Department in 1899.

"She was a trailblazer," Cooper said. "She served at a time when there was a tremendous imbalance in power of the races."

The police department started seeing many changes in the 1920s as women and African Americans began joining the ranks, according to a section about the Louisville Police Department in the Encyclopedia of Louisville.

Whedbee and other female officers were hired under the stipulation that they would "only be allowed to work with members of their own race."

The oath, pictures and a summary of Mrs. Whedbee were found in the collection of police artifacts put together by Morton Childress, acting historian and retired Louisville Police Department captain. He passed away in 2017. His late wife, was proud to let local media borrow a book written by Childress describing some of the hardships Whedbee had faced. For example, she not allowed to arrest white people.

Female officers at the time were restricted to patrolling dance halls, apprehending thieves in downtown department stores, working with children, and performing female body searches.

Though she cleared the path for female and minority officers, those hired in the following years were not without obstacles. A Courier Journal article in 1938 reported that Louisville's four policewomen, two African-American, were fired because there was "no work for them to do."

"We are discharging them for the 'good of the service,'" Safety Director Sam McMeekin told Courier Journal at the time. "They have no specific duties and practically do nothing... We are not finding fault with their work, there just doesn't seem to be any valid work for them to do."

By employing the women, McMeekin said the department was "being deprived of four able-bodied young men."

The fired policewomen told Courier Journal their work had consisted of searching female prisoners, assisting in "wayward girl problems," smoothing over family quarrels, making arrests on occasion and investigating.

White officers would not ride in police cruisers with African-American officers until 1965, and official policy providing equal opportunities to every officer regardless of race or gender was not established until 1973, Childress wrote.

Currently, 72 percent of the 1,246 LMPD sworn members are white males, and about 11 percent are white females, according to a department demographics report this month. About 11 percent are black males, and less than 2 percent are black females.

“Because of her I am,” retired LMPD officer Yvette Gentry said. “I retired from the police department almost five years ago, and black females only made up about 1 percent of that police agency.” Gentry said she thought about what it must have been like for Whedbee to work as an officer in that environment.

According to estimates in 2017 from the U.S. Census Bereau, 23 percent of Louisville's population is black.

Of the 246 in ranks higher than officer, 79 percent are white males, and 6 percent are black males. Less than 10 percent are white females, and 1 percent are black females.

Through near-freezing cold and overcast skies, dozens of people gathered to commemorate Whedbee. Sniffles were drowned by bagpipes playing “Amazing Grace,” and worn grave markers surrounded Whedbee’s new headstone.

The headstone, which displays both Bertha and Ellis Whedbee’s names and stories, is at Louisville Cemetery near the intersection of Poplar Level Road and Eastern Parkway.

'Trailblazer': First black policewoman may finally get her gravestone, written by Emma Austin (Courier Journal) June 2018; wfpl.org: City Pays Tribute To Louisville’s First Black Female Police Officer article by Kyeland Jackson (Nov. 2018); wave3.com, Late, but not forgotten: A memorial for Louisville’s first female African American police officer, written by Natalia Martinez (Nov. 2018); Kentucky Center for African American Heritage; Louisville Public Safety Museum

Officer Bertha Whedbee joined Louisiana Metro Police Department in 1922, decades before the Civil Rights movement and only two years after women got the right to vote.

Almost a century after changing the course of history for the city's police department, Louisville's first African-American policewoman is finally getting the recognition she deserves.

Sometime around 2017, now retired Louisville Police Sgt. Chuck Cooper came across mention of Officer Bertha Whedbee's story on Facebook. He found out she had become the first African-American female officer in March 1922 after having a petition signed by voters requesting she be appointed.

After some digging, Cooper and some other police officers discovered Whedbee and her husband were buried in an unmarked grave at Louisville Cemetery.

"We thought that was terrible," Cooper said. "She is one of our police family, and we take care of our family."

Along with a group of eight other officers, Cooper organized a campaign on GoFundMe, a crowdfunding website, to raise money to get a headstone for Whedbee and her husband, Ellis Whedbee, a doctor who co-founded Louisville's Red Cross Hospital and Nurse Training Department in 1899.

"She was a trailblazer," Cooper said. "She served at a time when there was a tremendous imbalance in power of the races."

The police department started seeing many changes in the 1920s as women and African Americans began joining the ranks, according to a section about the Louisville Police Department in the Encyclopedia of Louisville.

Whedbee and other female officers were hired under the stipulation that they would "only be allowed to work with members of their own race."

The oath, pictures and a summary of Mrs. Whedbee were found in the collection of police artifacts put together by Morton Childress, acting historian and retired Louisville Police Department captain. He passed away in 2017. His late wife, was proud to let local media borrow a book written by Childress describing some of the hardships Whedbee had faced. For example, she not allowed to arrest white people.

Female officers at the time were restricted to patrolling dance halls, apprehending thieves in downtown department stores, working with children, and performing female body searches.

Though she cleared the path for female and minority officers, those hired in the following years were not without obstacles. A Courier Journal article in 1938 reported that Louisville's four policewomen, two African-American, were fired because there was "no work for them to do."

"We are discharging them for the 'good of the service,'" Safety Director Sam McMeekin told Courier Journal at the time. "They have no specific duties and practically do nothing... We are not finding fault with their work, there just doesn't seem to be any valid work for them to do."

By employing the women, McMeekin said the department was "being deprived of four able-bodied young men."

The fired policewomen told Courier Journal their work had consisted of searching female prisoners, assisting in "wayward girl problems," smoothing over family quarrels, making arrests on occasion and investigating.

White officers would not ride in police cruisers with African-American officers until 1965, and official policy providing equal opportunities to every officer regardless of race or gender was not established until 1973, Childress wrote.

Currently, 72 percent of the 1,246 LMPD sworn members are white males, and about 11 percent are white females, according to a department demographics report this month. About 11 percent are black males, and less than 2 percent are black females.

“Because of her I am,” retired LMPD officer Yvette Gentry said. “I retired from the police department almost five years ago, and black females only made up about 1 percent of that police agency.” Gentry said she thought about what it must have been like for Whedbee to work as an officer in that environment.

According to estimates in 2017 from the U.S. Census Bereau, 23 percent of Louisville's population is black.

Of the 246 in ranks higher than officer, 79 percent are white males, and 6 percent are black males. Less than 10 percent are white females, and 1 percent are black females.

Through near-freezing cold and overcast skies, dozens of people gathered to commemorate Whedbee. Sniffles were drowned by bagpipes playing “Amazing Grace,” and worn grave markers surrounded Whedbee’s new headstone.

The headstone, which displays both Bertha and Ellis Whedbee’s names and stories, is at Louisville Cemetery near the intersection of Poplar Level Road and Eastern Parkway.

'Trailblazer': First black policewoman may finally get her gravestone, written by Emma Austin (Courier Journal) June 2018; wfpl.org: City Pays Tribute To Louisville’s First Black Female Police Officer article by Kyeland Jackson (Nov. 2018); wave3.com, Late, but not forgotten: A memorial for Louisville’s first female African American police officer, written by Natalia Martinez (Nov. 2018); Kentucky Center for African American Heritage; Louisville Public Safety Museum

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter